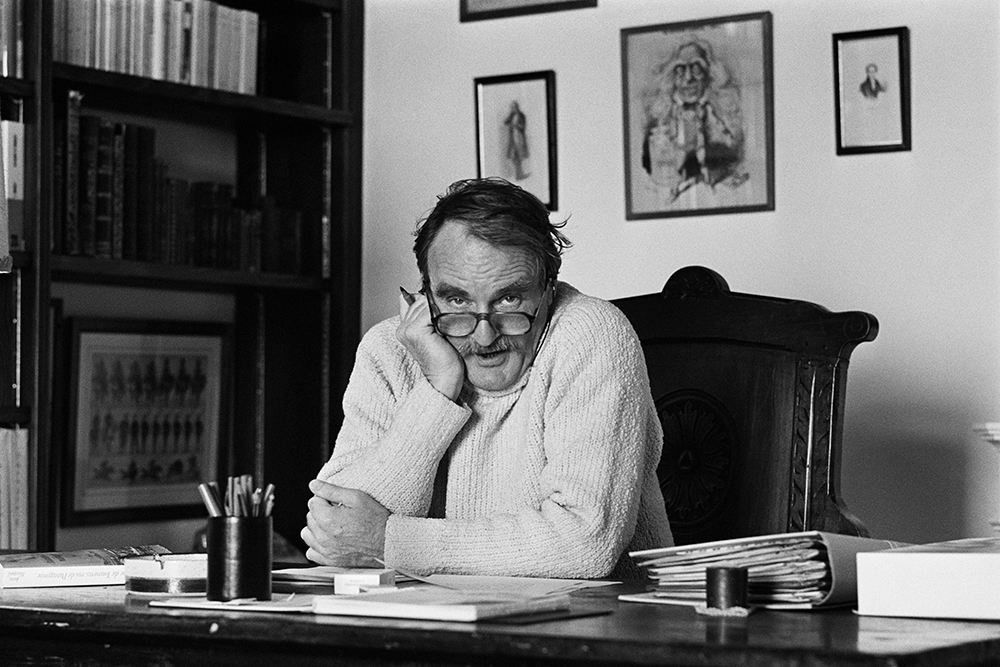

“Literature is mostly about having sex and not about having children.” So said the British novelist, occasional screenwriter and literary critic David Lodge, who died at the beginning of 2025 at the age of eighty-nine. Lodge, who had suffered from encroaching deafness for several decades, had not, in truth, been a major literary figure for a considerable period before his death.

This retreat into obscurity had not been helped by a trio of memoirs, beginning with 2015’s Quite a Good Time To Be Born, which perplexed critics — including this one — with their dour, downbeat and decidedly un-humorous tone. Few would have known, from reading them, that their author had once been regarded as one of the late twentieth century’s most accomplished comic novelists.

Yet if Lodge gave up novel-writing, the industry gave him up, too. With the noble exception of Paul Murray, and to some extent the British novelist Jonathan Coe, contemporary publishing now shies away from the kind of risk-taking, provocative and funny writing that Lodge specialized in throughout his heyday. This began in 1965 with his third novel, The British Museum Is Falling Down, and continued until 2004 with his last significant fiction, Author, Author, in which he fictionalized Henry James’s failed attempt to stage a play in London’s West End.

Forty years as a successful bestselling writer is a considerable achievement — then as now — but Author, Author was compromised by the near-simultaneous publication of Colm Tóibín’s more successful James novel The Master, and a disappointed Lodge made his feelings of frustration clear: even those disposed to be sympathetic to him murmured about sour grapes.

However, for an American readership, Lodge’s greatest reputation lies in two distinct, not unrelated, directions. The first was that he was, like Evelyn Waugh and Graham Greene, a Catholic novelist par excellence. The major difference among them was that Waugh wore his Catholicism with the arch zeal of the convert, and Greene used the literary (and autobiographical) complications of his faith as a kind of “get out of jail free” card when it came to questions of purgatory, damnation and the rest. Lodge, by contrast, took his Catholicism deeply seriously, and it is no exaggeration to suggest that it was as important for his writing as Philip Roth’s Jewishness was for his.

Lodge’s first novel, 1960’s The Picturegoers, established the then-twenty-five-year-old writer as an unusually perceptive and compassionate observer of Catholic values — he himself had observed a long, chaste courtship with his wife Mary, and remarked, “I had no prospects, no job, little money but it never bothered me. We didn’t really want children at the point they came along, but we got on with it” — and also as someone who specialized in serious comedy. His humor was rich, often dark and laugh-out-loud funny, but it was also based in matters of the heart and the spiritual, rather than on slipping on figurative banana skins.

He would refine this viewpoint in what many consider his masterpiece, 1980’s Souls and Bodies, which won the Whitbread Prize for Fiction. It dealt with the travails and religious difficulties of a group of friends, tracing their lives from university into middle age. There are relatively few comic novels that seriously consider the effects of Pope Paul VI’s 1968 encyclical Humanae vitae, which famously forbade contraception as against the teachings of the Church, but Lodge managed to absorb the moral and social complications of the papal edict in a wise, funny and deeply affecting book that should be better known than it is today.

For sheer entertainment value, though, it is Lodge’s “campus trilogy” of Changing Places, Small World and Nice Work that can hardly be bettered. American readers, especially, should take enormous delight in the first book, which is half a century old this year and still feels as fresh and hilarious in its satire on both British and American academia as when it was published. It revolves around the academic and sexual shenanigans that ensue when two professors, the ever-so-British Philip Swallow and the none-more-American Morris J. Zapp, swap places at their respective universities for six months.

Swallow hails from Rummidge (a thinly disguised caricature of Birmingham University, the red-brick institution where Lodge spent his academic life) and Zapp is a leading light of Plotinus in Euphoria, a dead-on parody of Berkeley in California. Swallow is bumbling, bewildered and bespectacled; Zapp — based on the literary critic and professor Stanley Fish, author of The Trouble with Principle — is a cynical and far more sexually assured figure. His prowess is stated early on when Lodge writes of him, “‘Jehovah…’ he would murmur out of the side of his mouth to girls who inquired about his middle name. It never failed; all women longed to be screwed by a god.” This prowess is furthered when Zapp successfully seduces Swallow’s wife, Hilary. However, by that point, Swallow has thrived at the aptly named Euphoria; he has (accidentally) slept with Zapp’s liberated daughter Melanie and, more intentionally, had carnal relations with Zapp’s frustrated, infuriated wife, the equally aptly named Désirée. Hilarity, genuinely, ensues.

The campus novel, as it became known, was a relatively recent innovation when Lodge wrote Changing Places. In Britain, Kingsley Amis’s great Lucky Jim more or less popularized the genre in 1954, but he was pipped to its invention by Mary McCarthy, whose 1952 book The Groves of Academe took a more somber approach to the lives and, indeed, loves of faculty members. Somehow, McCarthy, Amis and various other exponents of the campus novel made it seem de rigueur for all academics to be having wild and passionate affairs with one another, something that has continued in literature ever since. Novels as eclectic as Philip Roth’s The Human Stain, Michael Chabon’s Wonder Boys or J.M. Coetzee’s Disgrace have all taken it as read that, if you specialize in the study and meaning of literature, you will be a shameless horndog who is unable to resist the considerable temptations that students and fellow academics alike appear to offer.

As someone whose time in academe ended a couple of decades ago, I am ill-placed to testify as to the verisimilitude or otherwise of these fictitious representations of university, which often arrived laden with the taint of wishful thinking, but Changing Places offers considerably more sophistication than simple bedroom farce. Lodge himself spent a year at Berkeley in 1969 as an associate professor, allowing him to observe the tail-end of the Sixties from an American perspective, and his depiction of Euphoria is in equal parts affectionate and satirical, as the buttoned-up Swallow becomes progressively, happily undone by the opportunities and indulgences that California offers, from free love to outsized portions of deeply unhealthy food.

Still, if Swallow has found an earthly paradise of sorts, Zapp is less enamored by Rummidge. Lodge finds great comic capital in examining his home city and milieu from the perspective of an outsider. In one of my favorite moments in the novel, he brings together an academic’s detached insightfulness and mid-Seventies British broadcasting with hilarious results:

Waking early in his Rummidge hotel, he had flicked on his transistor and listened to what he took, at the time, to be a very funny parody of the worst kind of American AM radio, based on the simple but effective formula of having non-commercial commercials. Instead of advertising products, the disc jockey, pouring out a torrent of drivel generally designed to convey what a jolly, amusing and lovable guy he was, also advertised his listeners, every one of whose names he seemed determined to read out over the air, plus, on occasion, their birthdays and car registration numbers.

Now and again he played musical jingles in praise of himself or reported, in tones of unremitting jollity, multiple accidents on the freeway. There was almost no time left for playing records. It was a riot. Morris thought it was a little early in the morning for satire, but listened entranced. When the program finished and was followed by one of exactly the same kind, he began to get restive. The British, he thought, must be gluttons for satire: even the weather forecast seemed to be some kind of spoof, predicting every possible combination of weather for the next twenty-four hours without actually committing itself to anything specific, not even the existing temperature.

It was only after an authentic four successive programs of almost exactly the same formula — DJ’s narcissistic gabble, lists of names and addresses, meaningless anti-jingles — that the awful truth dawned on him: Radio One was like this all the time.

In person, Lodge was a severe, even stern presence. If students had signed up to his literature courses at Birmingham in the expectation of riotous laughter, they would have been disappointed. Yet he was also the man who invented, in Changing Places, the literary parlor game Humiliation, in which academics are invited to name the most famous book that they have never read. (The winner, a senior faculty member who comes forward with Hamlet, is duly fired.)

This tension between rigor and ribaldry, high moral ideals and the low comedy of human nature, makes Lodge’s novels not just entertaining period pieces but endlessly compelling and hilarious examinations of transatlantic mores. He loved academia, for all its flaws, and must have been horrified by its headlong rush to late-period, end-of-days wokery. He once said, “Universities are the cathedrals of the modern age. They shouldn’t have to justify their existence by utilitarian criteria.”

At a time when individual thought and free expression are more threatened than ever, Lodge’s novels, looking back to a happier, more open-minded time, seem a wishful encapsulation of a vanished Eden — in Rummidge as much as Euphoria. We can laugh at them — and we should — but we can learn from them, too.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply