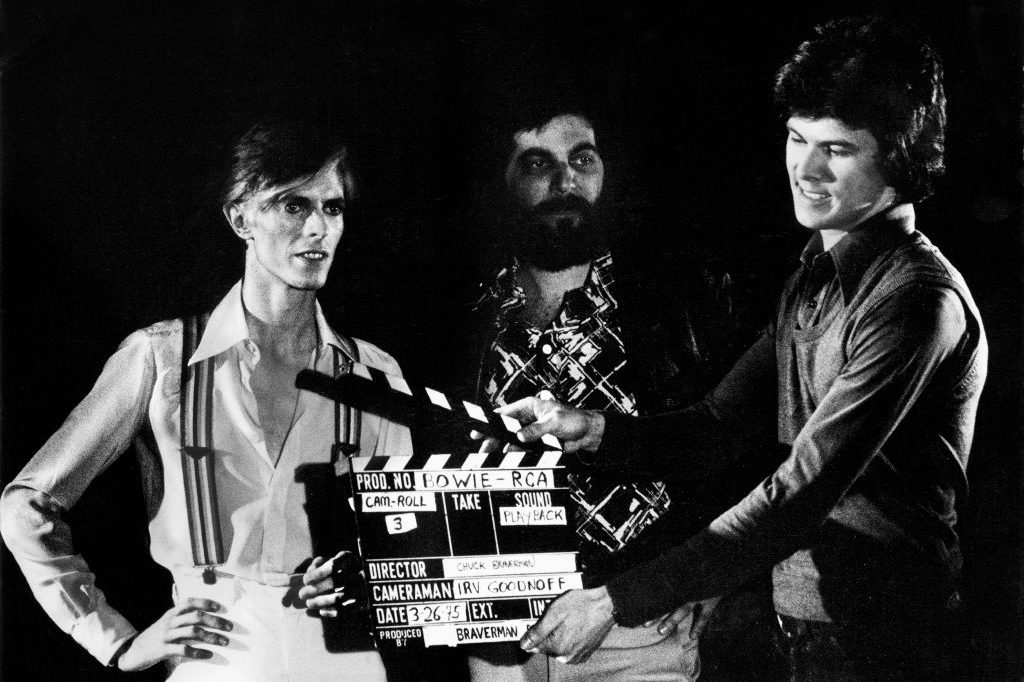

When the Puerto Rican guitarist Carlos Alomar first met David Bowie, he didn’t think a man could turn a whiter shade of pale. The singer looked emaciated; his complexion teetered on translucency, and weighing only 95 pounds, the only signs of life were a pulse and a mop of orange hair. It was the mid-Seventies, and Bowie was touring America deep in the throes of addiction — the “darkest years” of his life — surviving on a paltry diet of red peppers, cigarettes, milk and cocaine. Yet somehow, through the haze of these drug-fueled years, Bowie underwent a chameleonic reinvention of self and sound — and finally broke America.

Bowie had cast a sheen of suspicion over America as an aspiring artist, even admitting to hating it initially. Still, the country soon crawled underneath his skin, and New York would be where the singer drew his last breath on January 10, 2016. “[America] filled a vast expanse of imagination,” the singer confessed to Alan Yentob in a memorable scene from the 1974 documentary Cracked Actor, sipping from a carton of low-fat milk, the shadow from his fedora slicing itself across Bowie’s gaunt face. “The imagination can dry up in England if there’s nothing to keep it going,” he postulated. “It supplied a need in me, America; it became a myth land for me.”

To break the States, he knew he needed to change tack and recruit musicians who would force his progression as an artist. “I said he looked like shit and needed some food,” Alomar recalled of the day they met, insisting his wife make him some chicken and rice. Days later, Bowie pulled up in a limousine outside the guitarist’s house in Queens, imploring him to join a band he was assembling for a new album. The guitarist would serve as Bowie’s entry to the world of funk and soul, helping him craft a “plastic soul” record — a term he described as “the squashed remains of ethnic music as it survives in the age of Muzak, written and sung by a white limey.”

The 1972 album, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, had launched Bowie into the stratosphere in the UK, but it had failed to achieve traction across the pond. In a Frankenstein-like way, Bowie began to feel entrapped by his creation of Ziggy Stardust. What’s more, if he were to “cement his presence” in the States as he had hoped, it probably wouldn’t be with an alter-ego of a bisexual extraterrestrial rock star. He needed to fish in the mainstream.

In the mid-Seventies, soul and funk dominated the charts, with Al Green, Barry White and the Staple Singers leading the charge. Bowie had long been a devotee of soul, and in his early years as a mod musician, he wrote Sam Cooke tributes and covered James Brown songs on stage. He had been exposed to Brown’s music — whom he considered “the undisputed king” of soul — in French clubs, and the instrumentation in Brown’s Live at the Apollo would inspire tracks such as Bowie’s climactic track “Rock & Roll Suicide” — used dramatically in his swansong performance as Ziggy Stardust at the Hammersmith Odeon in 1973.

With more than a bit of help from Alomar, Bowie began to be introduced to musicians who would help shape the soul sound of Young Americans, including a then-unknown Luther Vandross. “We came along at a time when David was going through a concept change,” Vandross told Blues & Soul in 1976, “and I think we were partly responsible for it.”

In truth, the band and the vocalists were more than partly responsible. The sessions at Philadelphia’s Sigma Sound Studios — famously soul music’s hub — only took two weeks. With Alomar playing a crucial role in developing the album’s “plastic soul” sound, Vandross helped with vocal arrangements (especially with the title track and “Fascination”) while Ava Cherry and Robin Clark provided harmonically rich and textured backing vocals. Meanwhile, Willie Weeks, a bassist from the Isley Brothers, and Andy Newmark, the drummer for Sly & the Family Stone, built the album’s funk rhythm foundation for a “blue-eyed soul” feel. And, of course, the alto saxophonist David Sanborn — another legend lost only last year — gave tracks like “Win” and “Young Americans” fluttering riffs and solos as memorable as Bowie’s lyrics.

In the lyrics, Bowie presented a fantastical and idealized version of America, a country he still had muddled feelings about. “It’s about a newly wed couple who don’t really know if they like each other,” Bowie once said of the title track.

“Young Americans” was to be a cynical and observational portrait of America from an Englishman’s perspective. He references everything from Ford Mustangs and Barbie dolls, the resignation of Nixon over Watergate, McCarthyism to the darker side of the “American Dream.” When the lively track was blasted on the radio as a teaser two weeks before the release, the shift in style surprised everyone — goodbye glam-rock, hello Philly soul.

“Young Americans” was a breakthrough hit, climbing to number 28 on the Billboard Hot 100, but the last-minute addition of “Fame” would earn Bowie his first number-one in the States. In January 1975, Alomar, Bowie and John Lennon (to whom he had grown close over a mutual affinity for coke and Cognac) had a session at Electric Lady Studios in New York. In the studio, Bowie recycled a riff of Alomar’s and cooked up the track “Fame.” It was an instant classic, a biting funk-rock meditation on the shallowness of stardom carried by the killer riff, Lennon’s falsetto and Bowie’s sweeping vocals. A year later, James Brown, Bowie’s lifelong pin-up, would then borrow that same very riff for his song “Hot (I Need to be Loved, Loved, Loved, Loved).”

After the state-wide success of Young Americans — now reissued on vinyl this year to mark the 50th anniversary — Bowie further developed the sound on the 1976 album Station to Station (his best from this decade), where you can hear the plastic soul still swirling its way around tracks like “Golden Years” and “Stay.”

The starman-turned-soulman might not have considered the album his finest work, but it was a critical turning point in his evolution as a visionary artist who pushed boundaries up and into the astral plane. Another thing is also certain: all that came after Young Americans would not have existed without it. And aren’t we all the luckier for that?

Leave a Reply