At the Maddox Gallery in Gstaad, that strange, swanky village on the roof of Switzerland, Jay Rutland is showing me the latest exhibition by photographer to the stars Terry O’Neill. It’s a lovely summer day, clear sunlight streaming in through the windows, and the high peaks on the horizon have never looked more inviting, but the Alpine view pales beside the photos on the walls.

O’Neill photographed the world’s biggest rock stars and movie stars, the most famous people on the planet, yet these portraits are so fresh and intimate you almost feel you know them — not as aloof superstars but as fragile, familiar friends. Here’s Audrey Hepburn playing beach cricket with a piece of driftwood, grinning like a kid on holiday. There’s Richard Burton in a shower cap, fraught and pensive in the bath. The Beatles and the Rolling Stones stare back at you, young men on the brink of stardom. David Bowie and Elizabeth Taylor embrace, as she feeds him a cigarette. You’d never guess they’d only just met. That’s what Terry O’Neill does to you.

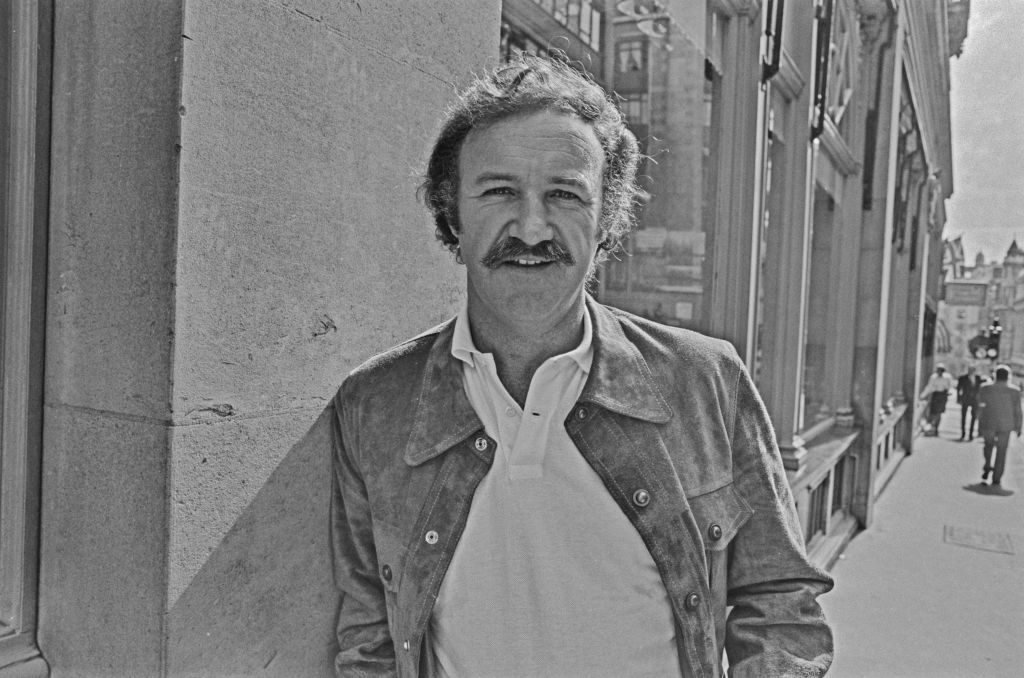

Terry O’Neill was one of Britain’s greatest portrait photographers, possibly the greatest. When it comes to peeling off the mask of fame, and revealing the real person beneath it, only David Bailey comes close.

This show features all his greatest hits, iconic images that transcend their subjects: Frank Sinatra and his minders looking mean and moody in Miami; Bernie Ecclestone surrounded by Formula One drivers, like a Roman emperor with his gladiators… Jay (Ecclestone’s son-in-law, and the creative director of the Maddox group of galleries) does a great job of guiding me round — he knew O’Neill and was very fond of him — but we both know the man himself should be talking me through these portraits. O’Neill knew about this show. He had a hand in planning it. But then last November he died of cancer, aged 81.

Yet this show doesn’t feel like a wake. It’s more of a celebration. These photos are too full of joie de vivre. ‘I always wanted my pictures to tell a story,’ said O’Neill. And they do.

He worked hard to make it look so easy, as all great artists do. He spent two days with Brigitte Bardot, waiting for the right moment, the right image — smoking a cigar, her long blonde hair blown across her face. Technically he was very good, but he wasn’t a photographer who worked his magic in the studio. It was all about the relationship. It was all about the shoot.

Terence Patrick O’Neill was born in Ilford, East London, in 1938. He was raised in Romford, on the Essex borders. His father was an Irishman who’d been transferred from the Ford factory in Cork to the Ford factory in Dagenham.

Terry left school at 14, hungry for a better life, but his first love was music. His dream was to go to New York, to try and make it as a jazz drummer. With the naivety of youth, he figured the best way to get across the pond was to become an air steward, but the closest he got was working as a photographer for BOAC at London Airport (now Heathrow).

O’Neill didn’t know it, but this was an ideal place to start. ‘The stars sat with everyone else,’ he recalled. ‘No-one minded you taking their picture.’ But the picture that got him his big break wasn’t of a big star — at least he didn’t think so when he took it. One day, in the departure lounge, he spotted a smart English gent, fast asleep, surrounded by African men in tribal dress. He took a photo and then discovered that this sleepy gent was Rab Butler, the home secretary. ‘It was completely by accident, just like Alice falling down the rabbit hole.’ Fleet Street soon came calling. The lad from Romford was on his way.

In 1963 he was sent to Abbey Road Studios to photograph a new band called the Beatles. He took them into the back yard and took a brilliant photo, but he preferred the Rolling Stones. Their R&B was closer to the jazz he loved, and he became close friends with Bill Wyman (they remained firm friends for life). His editor told him they were too ugly, but Terry knew they had star quality. His intense, edgy photos capture their raw animal appeal.

He could have remained a pressman forever, but he soon became weary of this hardbitten way of life. The tipping point was being sent to cover a plane crash in Oslo, in which British schoolchildren had died. ‘I suddenly realized that to work in Fleet Street you have to be inured to anything resembling emotion,’ he revealed. ‘I knew I couldn’t do it anymore. When I resigned the paper told me I’d never work again.’

It didn’t take him long to prove them wrong. He went to Hollywood, where he took many of his finest photos. This was the world he’d read about, the world he’d dreamt about since he was a boy. It was the golden age of portrait photography, when stars were still accessible. ‘If you worked with someone and they liked you, if you kept out of the way yet still came up with good pictures, they’d give their friends the nod,’ he said. His East End patter was an asset, but above all he was honest. ‘He had a natural ability to charm and disarm,’ says Jay. ‘He didn’t change, regardless of who he was with or who he was talking to.’ Stars felt safe with him. That’s why the pictures are so truthful. It was a partnership built on trust.

He photographed Sharon Tate a few days before she died. He’d been invited to her house the night she was murdered but he was too jetlagged to go. Inevitably, that innocent, hopeful portrait now has a macabre quality. Indeed, it’s spooky how many of the people on these walls died too young: Freddie Mercury, Keith Moon, Brian Jones, John Lennon…

He forged close relationships with David Bowie and Elton John, and took some wonderful photos of both of them, but the photo he’ll be remembered for forever is his daybreak shot of Faye Dunaway, the morning after she won her Oscar for Network, that prophetic film which foresaw today’s celebrity circus. There’s something haunting, almost frightening about it. It’s a picture of perfect emptiness, a scene from a film noir. There she is, alone beside the pool of the Beverly Hills Hotel, the morning papers strewn around her feet, her breakfast untouched on the table and that little gold statuette stood beside it. She’s got everything she ever wanted and now she knows it’s not enough. ‘He didn’t want an image of someone when they’d just won the Oscar,’ says Jay. ‘He wanted the image of what it’s like once reality sets in.’

Terry married Faye Dunaway but they didn’t live happily ever after. ‘Never marry an actress,’ he said, looking back. ‘You always have to live by their rules. I hated the Hollywood lifestyle. It’s a lonely world, because stardom fences you in.’ He’d got so close to the big stars — maybe closer than any other photographer, before or since — but now he was in too close. He’d stepped through the mirror. ‘It was one of his great regrets,’ says Jay.

[special_offer]

Terry returned to England, but the glory days were over. He was still just as good as ever. It was the industry that had changed. Now the publicists wanted to control everything. They wanted the same pictures in every magazine. They didn’t give photographers any creative freedom, so the paparazzi ran riot. It became a vicious circle. ‘Agents don’t want photographers and journalists hanging around actors anymore,’ he observed. ‘It’s all to do with power, which in turn makes the press become underhand.’

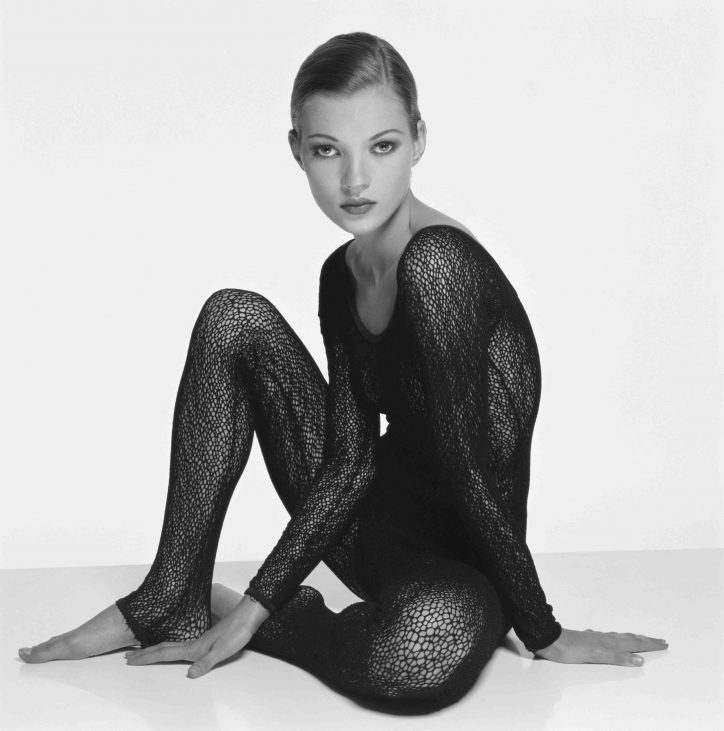

Yet the old magic was still there. The best photos in this show are from the Sixties and Seventies, but there are some stunning images from the Nineties and the Noughties too. I’ve never seen a better photo of Kate Moss or Amy Winehouse. Have you? Marilyn Monroe was the only subject that eluded him, the only one he wished he’d shot — the one that got away.

Every Picture Tells a Story is the title of this absorbing show, and indeed there’s a story behind every picture on these walls. However my favorite Terry O’Neill story is the only one without a picture. When Peter Sellers married Britt Ekland, Terry was invited to take the photos. He took some fantastic shots but sadly we’ll never see them. Unfortunately, the great photographer had forgotten to load the film.

This article was originally published on Spectator Life.