Americans are a vacationing people. We are those who mark the start of the summer with a ticket to a theme park, the end of high school with a tour of Europe and the commencement of retirement with a cruise trip. In fact, it is entirely fitting that the coronavirus pandemic first gripped the American consciousness thanks to reports of travelers marooned aboard cruise ships, or that, as virus cases at last start to flatline, many long for nothing more than for a few weeks at sea in the company of, say, Tony Orlando or Marie Osmond.

Some would say that this vacationing spirit is an inheritance from our empire-making ancestors in Great Britain. Perhaps, but our cousins across the pond acted first and foremost out of a colonizing instinct: these were men who sought to recreate their home country in Hong Kong or India. By contrast, and notwithstanding the persistent cliché of the Ugly American, most Americans travel, whether domestically or internationally, in search of genuine exoticism: to stand beneath Mount Rushmore or to gaze heavenward at the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. We are drawn to such places because of how dissimilar they are from our home turf. As the quintessential American globetrotter Daisy Miller said in Peter Bogdanovich’s fine 1974 film adaptation of Henry James’s novella of the same title (in a line that does not appear in James’s masterpiece but is entirely in keeping with its spirit): ‘There ain’t no Colosseum in Schenectady yet’.

Indeed, the American traveler, tourist or expatriate, alternately bewildered by and besotted with unfamiliar places, is one of the most enduring figures in our popular culture. Previous generations had James’s famously displaced protagonists, Mark Twain’s The Innocents Abroad and A Tramp Abroad, or Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms. In our own times we have been blessed with a cinematic artist with as sure a grasp of the American instinct for wanderlust as his forebears: the writer-director-producer John Hughes.

Hughes, who was born in 1950 and died in 2009, was something of a homebody in life and work. A native of Lansing, Michigan, he was a teen when his family relocated to suburban Chicago, where his most memorable films (Sixteen Candles; Ferris Bueller’s Day Off; Uncle Buck) were set and to which many a Hughes character (Steve Martin in Planes, Trains and Automobiles, Macaulay Culkin’s entire family in Home Alone) wished eagerly to return. In fact, after becoming a true power player in Hollywood, Hughes himself retreated to Chicago, remaining there until his untimely death at age 59.

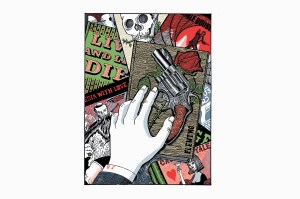

In fact, Hughes’s status as the rightful heir to James, Twain, et al. rests almost entirely on a single series: the Vacation films. Owing to their origins as a short story Hughes had penned for National Lampoon magazine, they usually released under the banner of that once-vaunted publication and, more often than not, starred Chevy Chase as the merrily jinxed suburbanite Clark W. Griswold and Randy Quaid as the coarse, rustic-minded Cousin Eddie.

Hughes wrote or co-wrote the key entries: National Lampoon’s Vacation (1983), followed by National Lampoon’s European Vacation (1985) and National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation (1989). Connoisseurs of the cinematic arts regret that Hughes had no involvement in Vegas Vacation (1997) or its made-for-television Chase-less sequel, Christmas Vacation 2 (2003), the Quaid-less reboot of the original film, Vacation (2015).

‘In my bedroom office during the snowstorm, I wrote “Vacation ’58”’, Hughes recalled in All-Story magazine in 2008, referring to his original short story. ‘My outline was a Rand McNally Road Atlas I had dug out of the trunk of my car. I plotted the shortest route from Detroit to the most distant continental US destination: Disneyland in Anaheim, California. I determined how many stops a family would have to make on such a trip, and where those stops might be’.

Hughes’s aims may have been modest, but in ‘Vacation ’58’ and the much-cherished film series that followed, he proved to be an able diagnostician of the good intentions, ill-advised impulses and deranged wanderlust that compel otherwise normal American families to pack up their belongings, hoist them atop a station wagon or relinquish them at a baggage check, and ride or fly to parts unknown.

Chase plays Clark W. Griswold with the same mixture of cheerfulness and incompetence he brought to his Saturday Night Live impersonation of Gerald Ford: part-innocent, part-rube and all-optimist, he’s Daisy Miller with a receding hairline. As the first Vacation comedy opens, the Griswolds — Clark, his weary wife Ellen (Beverly D’Angelo), and their indifferent young’uns Rusty and Audrey — are in the final throes of preparing for a summer road trip from Chicago to a sort of cut-rate Disneyland known as Walley World, a taxing trip that will see them snake through a large swath of the American Southwest but one that Clark eagerly anticipates with planned stops at Dodge City and the House of Mud.

‘It’s an awfully long ride, Clark,’ Ellen sensibly insists. Clark will have none of it: ‘The whole idea of a family vacation is to spend time together as a family!’

Upon commencing the journey, Clark remains undeterred by all manner of calamities, including a near wreck prompted by Clark lustily sharing the open road with a Ferrari-wielding Christie Brinkley; a gloomy stopover at the rundown farmhouse inhabited by the amiably luckless Cousin Eddie and his wife Catherine (Miriam Flynn), whose impoverished hamburger sandwiches anticipate present-day ‘meatless’ burgers; and the deaths en route of two unlikable creatures, the rebuke-prone Aunt Edna (Imogene Coca) and her vicious, Family Feud-watching canine companion, Dinky. The family scarcely has time to take in the glories of our fair land as the pressure mounts to arrive at Walley World, which, upon their arrival, is discovered to be temporarily closed — a plot twist plausible only because Clark was mapping out this trip pre-Google.

Surely no actual vacation could go so epically wrong, but Hughes’s genius is to situate the mayhem within the sweaty, sticky reality of a cross-country car ride: motel rooms and campsites and the like. Few films are as attuned to the boredom of traveling long distances or to the pettiness such trips can inspire, exemplified by the backseat brother-sister bickering. Rusty protests: ‘Audrey is eating peanut butter cups and smiling with it stuck all over her teeth!’ Clark decrees: ‘No eating in the car, kids!’

Given the runaway popular success of the first Vacation comedy, it was inevitable that a slate of sequels would follow. European Vacation is arguably the least appreciated film in the series but in many ways the most Jamesian. Trudging across Europe, Clark and family prove defiantly unadaptable to the carousel of cultures they encounter. Clark proves unable to navigate a roundabout in London, and endlessly circles Big Ben. Later, he causes the toppling of Stonehenge.

One wishes that additional globetrotting Vacation comedies had followed. Imagine the Griswolds in, oh, the Australian outback or Antarctica. But the subsequent films tamped down the travelogue aspect of the first two features. Thanks to incessant television broadcasts, Christmas Vacation has acquired a status roughly comparable to It’s a Wonderful Life, but the ‘vacation’ of the title refers not to a trip but to a break — that is, the traditional time-off given to worker bees in the English-speaking world at Christmastime. Setting aside his wandering ways, Clark cocoons himself in his lavishly decorated house and grows increasingly irritated at intruding visitors, including, inevitably, Cousin Eddie. After the Reagan-era expansionist vision of Vacation and European Vacation, Christmas Vacation suggested a post-Cold War retrenchment — ‘the end of history’ as told in Christmas lights.

Happily, the Griswolds were again in transit for Vegas Vacation, but the primary consolation of that so-so film was to be reminded that Chase and D’Angelo’s on-screen marriage had become the nearest contemporary equivalent to William Powell and Myrna Loy’s on-screen union as Nick and Nora Charles in the old Thin Man series.

By now the franchise has become so iconic that one can almost imagine Grant Wood’s ‘American Gothic’ repainted with the likenesses of Clark and Ellen Griswold, with Clark brandishing not a pitchfork but a road map. The enduring popularity of the Vacation series reflects not just the American appetite for travel, but also that old American virtue of gung-ho optimism. No matter how badly any one vacation goes, families will soon slough off the annoyances, inconveniences and disasters, and start planning their next trip. And there will always be a next trip.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2021 World edition.