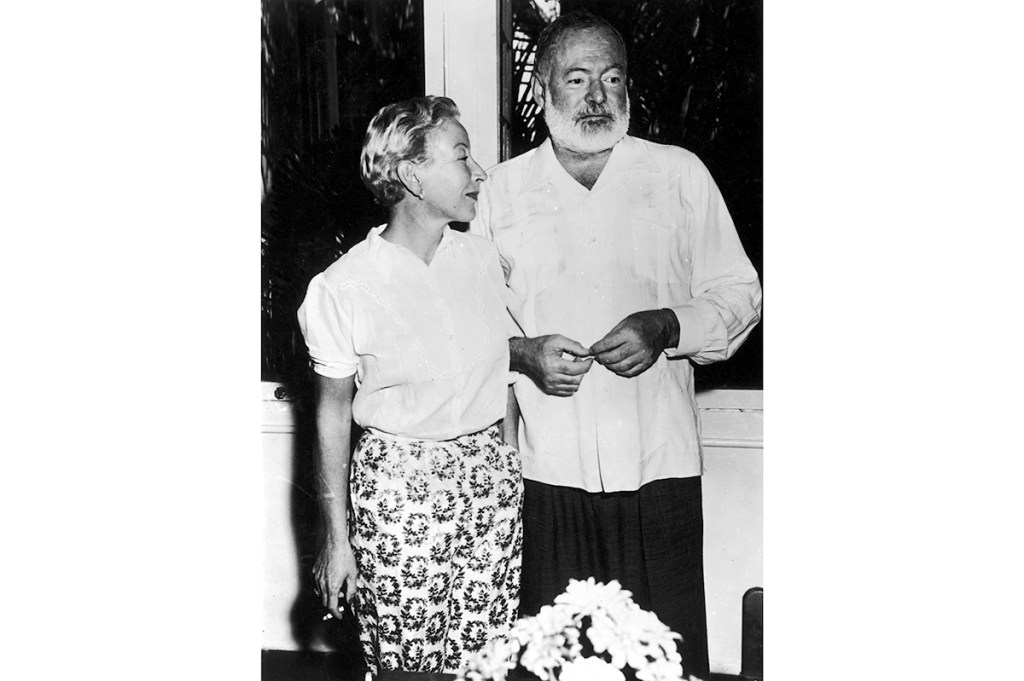

Close your eyes and imagine you’re married to Ernest Hemingway. Now, imagine it twice as bad, and you’ll be approaching the life story of Mary Welsh Hemingway.

Hemingway was married four times: to Hadley Richardson in 1921, to Pauline Pfeiffer in 1927, to Martha Gellhorn in 1940 and to Mary Welsh in 1946. In every swap, he divorced his current wife for her successor. Mary wrote her own memoir, How It Was, after Hemingway’s death in 1961. Now Timothy Christian has written a well-researched and intensely detailed look at the life of a fascinating woman who became the steward of Hemingway’s literary estate and reputation long before he died.

Mary Welsh was born in 1908 and raised in rural Minnesota. As soon as she could, she escaped to Chicago and college at Northwestern but dropped out when she married a fellow student in 1930. The marriage was brief, and in that same year Mary found work editing The American Florist for $75 a week — excellent money during the Great Depression — and soon moved on to the society page of the Chicago Daily News. When she met a fellow Daily News reporter, Leicester Hemingway, she confessed that she read everything his big brother Ernest wrote and wanted to know more about him. Be careful what you wish for.

By 1937, Mary was in London writing for the Daily Express — courtesy of its owner Lord Beaverbrook, who was taken with her. After proving her worth with a July profile of Amelia Earhart, who had vanished over the Pacific earlier that summer, Mary began reporting on Hitler and the march toward war. She married a fellow journalist, Noel Monks, but the union was compromised by his absence in Singapore and her penchant for love affairs with left-wing politicians and writers; she described wartime London as “a Garden of Eden” for single women.

Ernest Hemingway came to the British capital for the first time in May 1944, as the RAF correspondent for Collier’s Weekly. Hemingway and Mary met at lunch soon after he arrived, and he immediately asked to see her again. Hemingway told her, “I want to marry you. You are very alive. You’re beautiful like a May fly.”

Mary was thirty-six and Hemingway was nine years older. He was smitten, and she was flattered with the attention from such a literary celebrity. In mid-June, she and Hemingway went to bed together, but “Mr. Scrooby” — which I regret I now know was Hemingway’s nickname for his penis — demurred. Hemingway continued courting her in person, when he was infrequently in London, and, more successfully, with letters from Europe, where he was embedded with the Allied forces. They became lovers in Paris in August 1944, as the Allies rolled in and reclaimed the city. Hemingway took her to the places he and Hadley had gone twenty years before. His friend Pablo Picasso agreed to Ernest’s request to paint Mary nude, but she refused to go.

From the first, Hemingway comes across as a needy, bossy, aging man, interfering and not particularly attractive — apart from his celebrity. And yet, that August, Mary promised to marry him, after they were both divorced — doing so, Christian tells us, because Marlene Dietrich had persuaded her to, the morning after Hemingway had slapped Mary in the jaw while they were in Paris. This pattern of behavior, marked occasionally with passionate happiness and bright spots of kindred spirits enjoying affection for each other, continued for seventeen years.

Mary quit her job — she had been writing for Time magazine since 1940 — and she and Hemingway married in Cuba in 1946, at Finca Vigía, the house he had bought and lived in with Martha. Martha’s belongings were still there when Mary arrived. The marriage ceremony was in Spanish, and Mary, who didn’t speak the language, wasn’t sure what she was saying. “Pop Hemingway and I were not made for each other,” she thought, even at the time, but Mary always stayed. An ectopic pregnancy nearly killed her in Wyoming in 1946 — Hemingway saved her life by finding a vein in her arm and administering plasma himself when doctors had despaired, a story told gruesomely and memorably by Christian in his prologue. Mary was unable to have children thereafter, and Hemingway blamed her cruelly.

She bleached her “peanut-butter” hair platinum for him, helped raise his two youngest sons, Patrick and Greg (from his marriage to Pauline), when they were visiting, learned to shoot to accompany him hunting though she hated killing living things, typed up his manuscripts and fretted over his increasingly poor health. When they went on a delayed honeymoon through Italy in 1948, Hemingway took Mary to visit the places where he was injured (and had recovered) as a young ambulance driver in World War One. They had perhaps the best time of their marriage in Florence and Venice, and on Torcello — until Hemingway fell for a girl just his age at the time when he’d been in Italy as a teenager himself, an eighteen-year-old Venetian named Adriana Ivancich. Mary generally ignored Hemingway’s infatuations, but Adriana, the model for Renata in Across the River and Into the Trees (1950), was difficult for her to tolerate.

After the success of The Old Man and The Sea (1952) — interestingly, it was at Mary’s insistence that Santiago survived — and Hemingway’s 1954 Nobel Prize in Literature, the couple traveled restlessly. At first they enjoyed Africa, hunting and engaging in sexual role-playing, with Mary as a boy. Then two consecutive light-plane crashes in Africa nearly killed them both, and the Hemingways were reported dead by the world’s newspapers until they made it to Mombasa. Hemingway’s serious injuries hastened his decline.

They missed their home and friends in Cuba immensely, and the Bay of Pigs invasion in April 1961 only contributed to Hemingway’s depression. Mary kept his illness quiet, traveling with him to psychotherapy appointments and for electroshock treatments. And, finally, she denied that his death on July 2, 1961 was a suicide, claiming first that it was an accident, and then that Hemingway had only been “looking” at his beloved W&C Scott shotgun when it suddenly discharged. Mary did not admit that he had killed himself until an August 1966 Look magazine interview with Oriana Fallaci.

Hemingway’s widow was an assiduous, fierce and disingenuous defender of her husband’s legacy. When they visited Paris in 1959, a porter at the Ritz Hotel brought Hemingway two suitcases he had left there in the 1920s. In them were notebooks and pages of typescript from his earliest days in the city. Back in Idaho, he tried to use these reminiscences to complete the book that became A Moveable Feast (1964). Mary was the one who finished it. Christian does not report that Charles Scribner and others begged her to redact some of its viler slurs, chiefly about people long dead and unable to reply like Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, but Mary refused. Seán Hemingway, Hemingway’s grandson, prepared a new, and far truer, edition of the book from the original papers in 2009.

Because of President Kennedy’s help in retrieving Hemingway’s papers from Cuba, Mary donated them to the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston. Keeping for herself drafts and letters she wanted for her own writing, Mary sent his papers, and hers, to the library piecemeal over the course of years. After completing her memoir How It Was (1976), Mary became frail and unwell, which was exacerbated by drinking, chiefly gin. She soldiered on, increasingly infirm of mind, until she died in 1986 at the age of seventy-eight.

Mary Welsh is a fascinating subject for a biography. Mary Hemingway, though she dominates this book, is less so. Christian’s portrait of an intelligent, attractive and accomplished woman bullied and abused by the man she loved and cared for swiftly becomes both unrelenting and distressing, despite being well-written. I wish for her sake that Mary had been married to a good man, instead of a great one. She was too generous to Hemingway while he lived, and too protective of him after his death, often to her own detriment in both cases. When Mary told Fallaci, “Writers are lonely persons, even when they love and are loved,” surely she spoke not only about Hemingway, but also for herself.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2022 World edition.