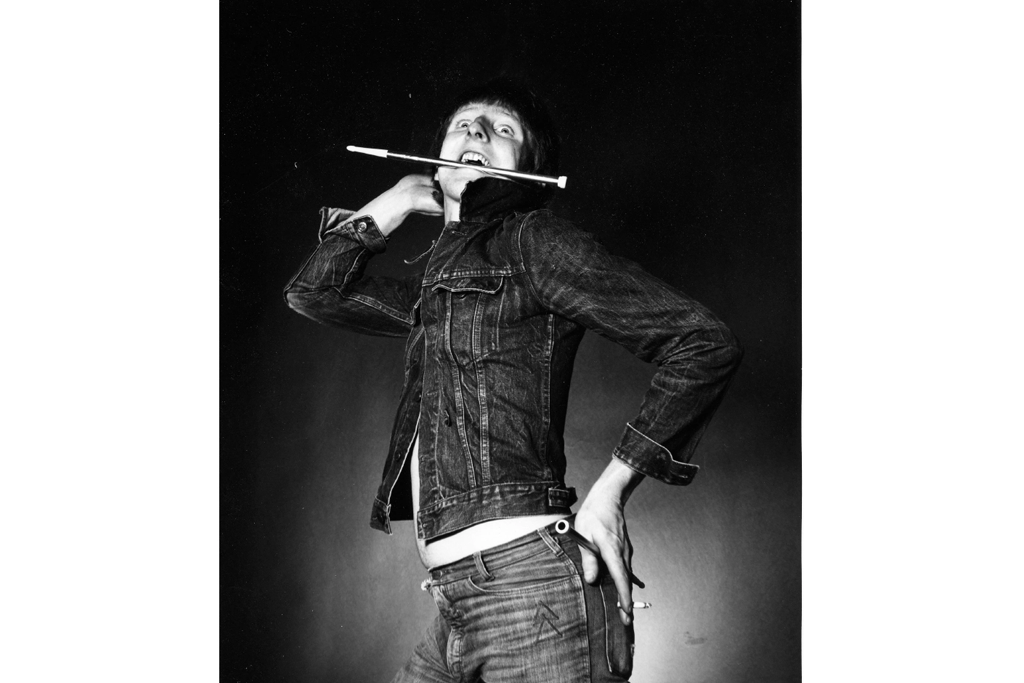

Most former punks end up touring the nostalgia circuit or cropping up at conventions. Not Christopher John Millar, aka Rat Scabies. When Scabies hit middle age, the legendary drummer with the Damned began to hunt for the Holy Grail. “We all started off criticizing government and I’ve ended up looking for pixies,” explains Scabies.

In 2005, the music journalist Christopher Dawes wrote a rollicking account of a trip he took with Scabies to the epicenter of it all, Rennes-le-Château, a tiny village atop a rock overlooking the River Aude in the Languedoc. Rat Scabies and the Holy Grail has taken its place as a minor gonzo classic. Dawes lived across the road from Scabies in the London neighborhood of Brentford and gradually got drawn into a world of odd theories and strange coincidences. “I knew he’d be hooked and anyway this kind of yarn made me sound interesting,” Scabies tells me.

We are sitting in Scabies’s local pub and he’s still obsessed with that yarn and could be tempted back to look for treasure again — even though he didn’t find it last time.

“Nobody has found anything yet. People suddenly say they’ve found it and ‘X marks the spot,’ but they don’t do their research properly. It is still out there. Imagine a cave the size of a Tesco store full of gold and manuscripts and treasure. Full of history and knowledge. That’s what we are looking for.”

Scabies’s dad lit the spark with this tale of extraordinary riches hauled to France by Templars. The story takes in hidden Nazi treasure, the lost Kings of France, sacred geometry and, of course, François-Bérenger Saunière, who is key.

Saunière was a local lad-turned-Catholic priest, who showed up in Rennes in 1885 and acquired an unexpected fortune, which some believe was part of the Holy Grail hoard, and many others claim was built up fraudulently. These days, the Saunière Society looks after the legacy and gathers like-minded people. Scabies was its one-time chairman.

He’s not the only one who has been caught up in the hunt. Marc Bolan was too. When they toured together, Scabies and Bolan ended up sitting at the back of the bus “talking about the grail and Atlantis. Marc told me he once met a wizard who could fly, and that kind of got him interested.”

Scabies was brought up by his grandparents — a working-class boy dreaming about making it as a drummer. And make it he did. The Damned released the first UK punk single “New Rose,” the first punk studio album Damned Damned Damned, and was the first punk band to tour the US. They were also the first punk band to break up and reunite.

If you aren’t working class and didn’t live through 1970s Britain, it’s hard to imagine just how hopeless it all felt. When the Sex Pistols sang “no future for me,” we all agreed. Punk wasn’t nihilism to us; it was a statement of fact.

“The 1970s were terrible. People say there were no jobs with Thatcher. But the problem was that the jobs were so bad that no one wanted to do them anyway.”

When Scabies went to see his teacher, he told him he wanted to be a drummer. He didn’t mind where; perhaps in an orchestra pit at the theater. His teacher laughed and told him to join the army. I had a similar experience on leaving university with an English degree and being told I should become a “rough, tough transport manager.”

In this bleak period he was stopped by the police. They ran his name through the system to check up on him. What came back was “Known but not wanted.”

Scabies kept on drumming. “You don’t have to play loud to be good. You don’t have to be Buddy Rich, you can be Ringo Starr as long as you don’t muck up the song. Don’t make the song worse.”

Before the Damned, Scabies played in local bands and he knew that punk was a once-in-a-generation opportunity to change his chances. The alternatives, if it hadn’t come off, were a future in a factory or prison. Drums and guitars and punk bands were a way out. “When you think of Elvis, he understood that. He came from nothing, but he gave me, people like me, the belief that that didn’t matter. Bill Haley was a pig farmer, but he sold millions of records.”

Unusually for this scene, Scabies only has fond memories about his contemporaries. Nick Lowe, “the David Niven of music”; the Stranglers, “great chaps but they weren’t really a punk band”; the Ramones, “really nice normal people but odd atmosphere in their dressing room”; and his bandmate Brian James, “the only person who really knew what punk was.”

Once Scabies finally found some treasure it didn’t yield any greater happiness. “When I got paid for the five Damned reunion gigs I didn’t know what to do with the money anyway.”

The band’s soundscape was varied. “Brian James loved the Stooges. Captain Sensible was proggy. Dave Vanian loved the kind of stuff you’d hear at a fairground when we were young, and I loved anything that was loud — well, anything with lots of drums on.” And Rat’s favorite Damned song is still “Neat Neat Neat” because it has a great tune and shows they could play a bit.

It explains why the band moved quickly on from punk and had strong psychedelic and goth influences. For their second album they hired Nick Mason of Pink Floyd as the producer and brought in a clarinet player, which at the time felt like lunacy.

And why was he called Rat Scabies? Punks needed stage names more than most — not least so the authorities couldn’t chase them down and cut off their state benefits. “I didn’t come up with the name Rat Scabies, but at the time I actually had scabies and was itching everywhere and then a rat got into the rehearsal rooms and ran around. But the truth is that I liked the name Rat because I probably looked a bit like one.”

When I look in the mirror, I have a constant reminder of my brush with the Damned. I went to see them in the late 1970s. Rat threw a drumstick into the crowd, and it struck me straight in the mouth. I lost a front tooth and have had a gap there ever since, and the crown that replaced it is now wonky. A bit like Rat. A bit like me too.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.