This article is in The Spectator’s January 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.

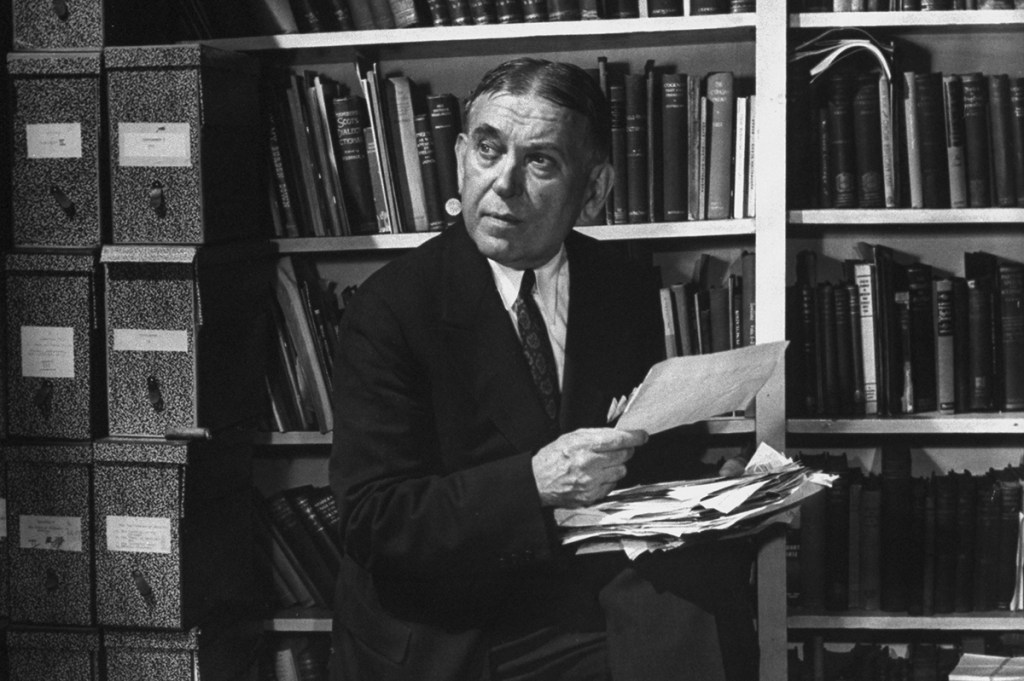

In this age of dim digitized media in which E.J. Dionne and David Brooks are honored as distinguished columnists, the byline Henry Louis Mencken is virtually forgotten. Mencken, who died in his sleep 64 years ago this week after listening to Die Meistersinger on the Saturday afternoon broadcast from the Metropolitan Opera, is unlikely to be remembered by the mediacrats who abhor everything the man stood for.

Yet Mencken in the 1920s was one of the most celebrated figures in America, and even the western world. The erstwhile bad boy of Baltimore has been alternatively described as a ‘Jeremiah come to pass judgment’ on a decadent and mentally paralyzed America, the ‘American Nietzsche’, the heir to Voltaire and Swift, the greatest journalist of his time, a Communist agitator and the secular Antichrist.

Detractors have dismissed him for his alleged superficiality as a social critic and political commentator, for his lack of serious ideas and for his bombastic style. Other more discerning critics have admired him as a foremost practitioner of rakish literary English. (The highly serious Walter Lippmann wrote that Mencken ‘calls you a swine and an imbecile and increases your will to live’.) But to view him as superficial is to misunderstand both the man himself and his work. Ideas and theories were not Mencken’s meat and drink. Real people and social comedy were.

Henry Louis Mencken came into this world on September 12, 1880, the son of August and Anna Abhau Mencken. The first of the Menckens in America landed in Baltimore in 1848 and founded a cigar business which August inherited and in which he remained, despite his interest in engineering. Doubtless on account of that interest, he sent Henry to the Baltimore Polytechnic Institute. Upon graduating, Henry dodged what he called the ‘Herr Professor Doctors’ of higher education, and in 1899 he went to work at the Baltimore Morning Herald as a beat reporter. From there he found his way to the Baltimore Evening Sun, with which his name soon became synonymous.

Mencken’s first published work was a poem, ‘Ode to the Pennant on the Centerfield Pole’, written when was 16 years old about… baseball! The year before starting at the Morning Herald, he began a novel set in Elizabethan times but abandoned it almost immediately; he was, as his wife noted, a Victorian at heart. Even as his journalistic career thrived, he also set up as a short story writer. The stories, if derivative, were fresh and vigorous, though their author, in sophisticated maturity, considered them ‘hollow, imitative, and feeble’. In these early, already beery days he published Ventures into Verse too, also more or less disavowed afterward. Mencken’s interest was shifting from what the pedagogues erroneously distinguish as ‘creative’ writing to criticizing fiction written by people who were better at it than he was.

It is often forgotten that before the early 1920s, Mencken was better known as a literary critic than as a political one. His first published book after Ventures was a treatise on Shaw and his plays; this was followed by The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche (1908), the first book-length study of Nietzsche in English. But it was during his joint editorship of the Smart Set with the drama critic George Jean Nathan that Mencken gained a reputation as a literary critic of distinction and even genius, and as a champion of young American novelists such as Theodore Dreiser and Sinclair Lewis, as well as European romancers including Joseph Conrad.

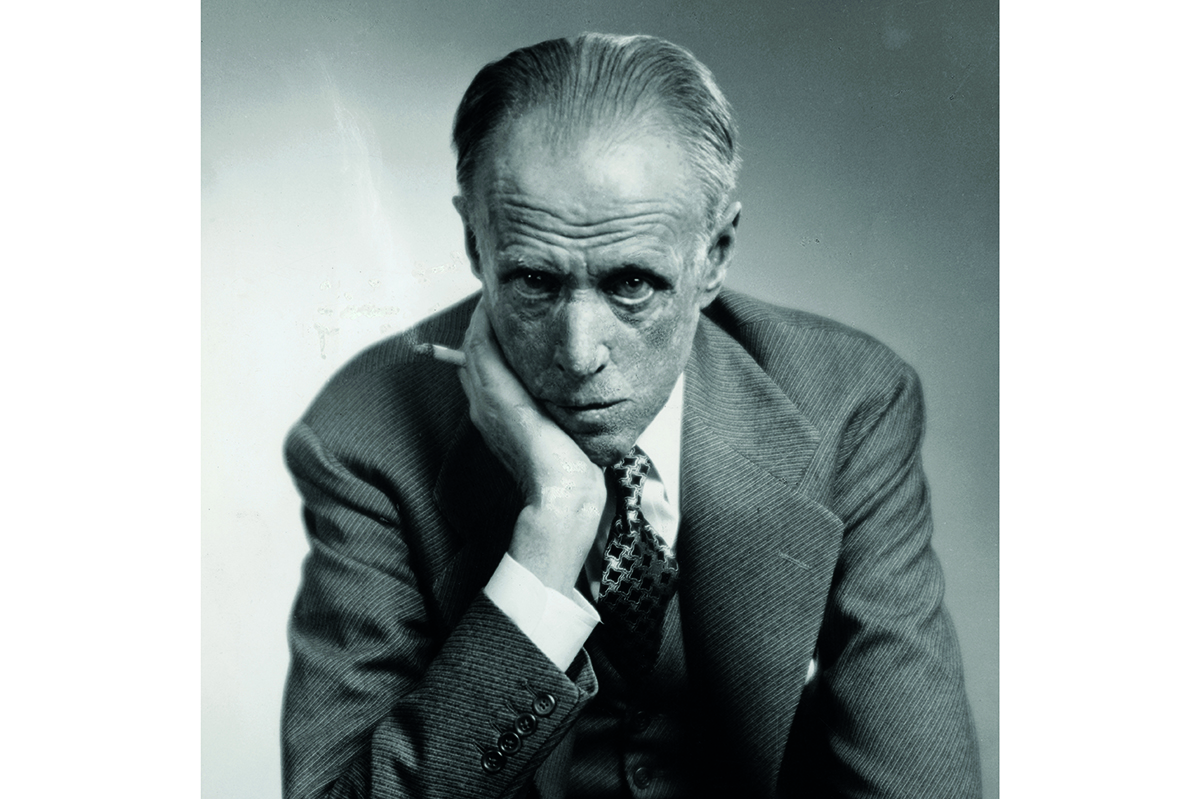

It was only after Mencken and Nathan left the Smart Set and co-founded the American Mercury in 1924 that his interest, to the dismay of the literati he had boosted at the Smart Set, turned chiefly to politics and social issues. Yet he remained friendly with and wrote about Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Faulkner, Willa Cather, Dos Passos, Edmund Wilson and others. As these novelists had benefited from his careful criticism and attention, so Mencken had profited from a careful reading of their work. It was arguably from that experience that his later skill as a narrative writer of journalistic nonfiction and a memoirist developed.

‘America’s most hated citizens’

Some of Mencken’s best work is in the autobiographical Days series (like Dos Passos’s USA Trilogy but much better), published in the early 1940s after his ‘Tory radical’ politics had lost their charm for readers during the Depression. Somehow, even these three wonderful volumes, amounting to one of the most evocative and colorful social records of American life in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, have failed to provide literary scholars with the clearest clue to the fact that Mencken was not primarily a journalist, a critic, a debunker, a satirist or even, despite his enormous and definitive The American Language, a philologist. He was all of these things, but at bottom he was a novelist working in his chosen medium — nonfiction.

Mencken elaborated a personal vision of America and Americans based on unflinching and unsentimental observation and heightened by a powerful comic imagination grounded, though he would have indignantly denied it, in a profoundly moral view of man and society. In this respect his vision was Dickensian. Both worked in caricatures, which, though piously deplored today as stereotypes, still give the shock of recognition.

Mencken’s Coolidge and Hoover, his W.J. Bryan and his Roosevelts, are as much ‘characters’ as Mr Pickwick or Bill Sikes. The delight they afford varies according to the reader’s ability to appreciate literature for itself, not for its political opinions and morals. Mencken, like all the important social novelists — Stendhal, Balzac, Zola, Faulkner, Powell and Waugh — created eccentric but recognizable worlds, populated with convincingly drawn people representative of their time and society.

Mencken’s novel is the whole of his work, structureless in the formal sense, but written on coherent and sustained themes and embracing many recurring characters. A Frenchman stumbling upon it might recognize it as a kind of nonfictional roman-fleuve. Consider the superb ‘Gore in the Caribbees’ (1942) from Heathen Days, an exercise in what Tom Wolfe called the New Journalism. Mencken’s account of the Cuban Revolution of 1917 — a classic comic opera affair of the Latin American type — combines hilarity, a generous though limited appreciation of Cuban culture and a perfectly poised satirical style that spares neither Latin political competency nor the silliness and vulgarity of American newspaper journalism.

Here is the final paragraph of ‘Gore’, describing the conclusion of José Miguel Gomez’s failed attempt to take back the Cuban presidency in 1917 by force of arms, for which he was originally sentenced to death:

‘President Menocal was a very humane man, and pretty soon he reduced José Miguel’s sentence to fifty years, and then to fifteen, and then to six, and then to two. Soon after that he wiped out the jugging altogether, and substituted a fine — first of $1,000,000, then of $250,000, and then of $50,000. The common belief was that José Miguel was enormously rich, but this was found to be an exaggeration. When I left Cuba he was still protesting that the last and lowest fine was far beyond his means, and in the end, I believe, he was let off with the confiscation of his yacht, a small craft then laid up with engine trouble. When he died in 1921 he had resumed his old place among the acknowledged heroes of his country. Twenty years later Menocal joined him in Valhalla.’

As the Days suggest, Mencken, who reread Huckleberry Finn annually and shared Hemingway’s admiration of Mark Twain, learned much of his comic narrative technique from the man he fondly referred to as ‘Old Mark’.

Or take ‘Imperial Purple’, one of Mencken’s famous Baltimore Sun columns, written in 1931. The subject of this small gem is the tawdry, tedious and trivial pomps and perquisites of the American presidency. The column is at once a prose poem, an inspired satire and a short-short story in which nothing really happens save for three very minor events described in the final three sentences.

‘All day long the right hon. lord of us all sits listening solemnly to bores and quacks. Anon a secretary rushes in with the news that some eminent movie actor or football coach has died, and the president must seize a pen and write a telegram of condolence to the widow…anon there comes a day of public ceremonial, and a chance to make a speech. Alas, it is discovered, at the last minute, to be made up of gentlemen under indictment, or at the tomb of some statesman who escaped impeachment by a hair. Twenty million voters with IQs below 60 have their ears glued to the radio; it takes four days’ hard work to concoct a speech without a sensible word in it. Next day a dam must be opened somewhere. Four senators get drunk and try to neck a lady politician built like an overloaded tramp steamer. The presidential automobile runs over a dog. It rains.’

This article is in The Spectator’s January 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.