Big Caesars and Little Caesars is an entertaining jumble with no obvious beginning, middle, end, or indeed argument. But there is an intriguing book buried underneath it which asks more or less this: where does Boris Johnson stand in the historical procession of would-be strongmen or, as Ferdinand Mount calls them, “Caesars?” How successful was Johnson’s attempt — overshadowed by the Brexit noise, his personal scandals and his Bertie Wooster act — to turn Britain into a more authoritarian state?

Mount, now eighty-four-years-old, comes at this from a long Tory past that in recent years he has seemed to disown. Though he spent most of his career as a journalist and novelist, he was, also, incongruously, head of Margaret Thatcher’s No.10 Policy Unit in 1982-83, just as she began remaking the country. He described this stint in his 2009 memoir Cold Cream: My Early Life and Other Mistakes (a much better book than the new one). A cousin of David Cameron and nowadays a liberal Remainer, Mount isn’t keen on today’s Tory party.

Big Caesars and Little Caesars often reads like two almost unrelated books stuck together: an already outdated polemic against Johnson, and a collection of entertainingly retold secondhand research about historical dictators and thwarted wannabes. The book, Mount admits early on, “will jump about in a way that may disconcert some readers.” He disdains chronological order. He is overambitious, covering material on which he has no expertise. His riff on António Salazar’s Portuguese dictatorship, for instance, seems to have come straight from The Rough Guide to Portugal: “The concept of saudade – yearning, nostalgia – was all the rage, and so was the new melancholy song of love and loss, the fado (fate).” I don’t think I’m being biased in recommending Strongmen by my Financial Times colleague Gideon Rachman, or The Despot’s Accomplice by Brian Klaas as better guides to today’s rash of Caesars.

Mount starts by suggesting he wants to find patterns across time: “How do these Caesars gain power? What are their vital ingredients? How do they normalize their breaches with constitutional tradition?” But, as he soon admits, there are few patterns in history:

The local causes of breakdown which enable a would-be Caesar… to step into the breach are strikingly varied…. Secondly, the causes are not tied to any particular stage of economic or social development.

It is true that history is patternless, but that exacerbates the patternlessness of this book. In the hands of an old-fashioned Whig or Marxist historian, Big Caesars and Little Caesars could have marched more satisfyingly to a resounding (albeit wrong) conclusion.

As Mount explains, would-be Caesars can emerge any time, in any society. In fact they find surprisingly fertile ground in established democracies. As Max Weber noted, once you directly elect the leader, you create opportunities for charismatic individuals who can charm the electorate. No wonder that Johnson argued, in defiance of the British constitution, that as prime minister he had a personal “mandate” from voters. Uncharismatic figures, such as Salazar, do better in dictatorships, where voters’ tastes don’t matter.

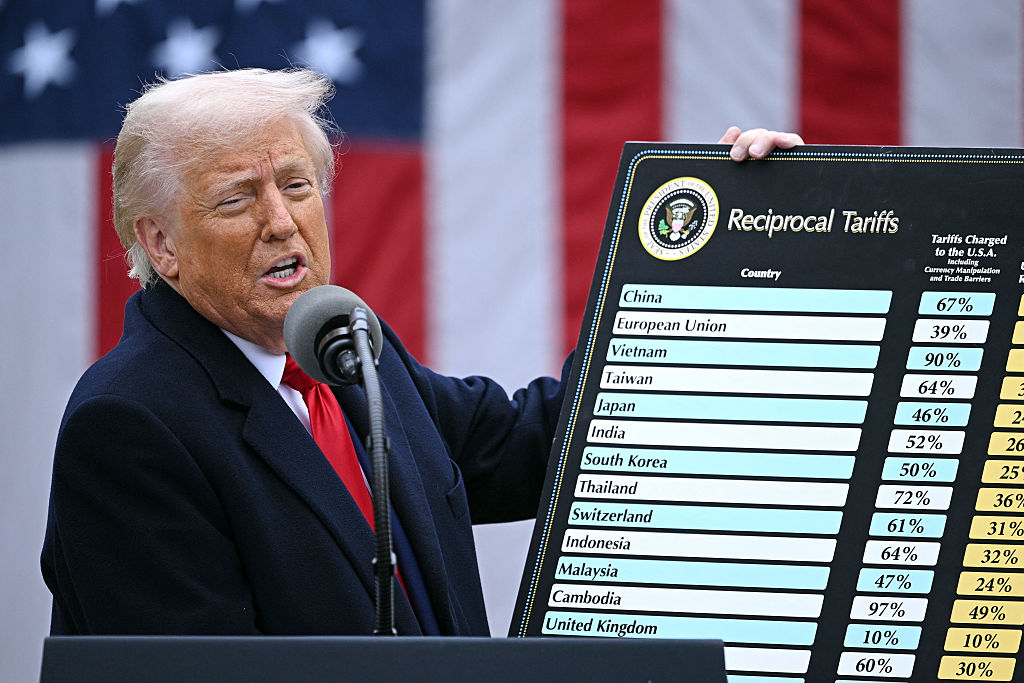

The most recent Caesar-friendly innovation is social media. Mount quotes Donald Trump: “I love Twitter… That’s the only way I have to communicate. I have tens of millions of followers. This is bigger than cable news.” Mount writes:

Twitter plus Fox News provided Trump with unmediated access to his core voters, a closeness that probably hadn’t been available since ancient Greeks and Romans crowded into the Agora and the Forum to hear it straight from Demosthenes and Cicero.

Mount’s attempts to connect Johnson, and occasionally Trump, with past Caesars are underwhelming. Most of the parallels are obvious: e.g. Caesars despise parliaments as talking-shops for the uncharismatic and put out lying propaganda. Jacques-Louis David’s painting of Napoleon crossing the Alps on his white horse, for instance, conceals the fact that Boney and his men slid down the icy Great St. Bernard Pass “on their bottoms.”

But Mount does occasionally cast light on the Caesarian modus operandi. One commonality these people share is contempt for their own supporters. Here is Charles de Gaulle in retirement: “The French no longer have any national ambition… I amused them with flags.” And Hitler:

The receptivity of the great masses is very limited, their intelligence is small, but their power of forgetting is enormous. In consequence of these facts, all effective propaganda must be limited to a very few points and must harp on these in slogans.

And Trump’s adviser Steve Bannon told the designated ghostwriter of a Trumpian book about the Deep State: “You do realize that none of this is true?” Johnson and Trump, too, aimed to fool some of the voters all of the time.

Many Tories will reject the categorization of their beloved “Boris” as a would-be Caesar — albeit, in Mount’s own terminology, only a “Little Caesar,” who seeks a more authoritarian government rather than full-blown dictatorship. Johnson doesn’t look Caesarian. But Mount quotes Johnson’s former employer at the Telegraph, the ex-convict Conrad Black: “He’s a fox disguised as a teddy bear.”

Mount makes a good case for Johnson’s strongman impulse. His argument rests on Johnson’s “five acts” to increase the power of prime minister — a position that he expected to keep for nearly a decade until he tripped himself up with Partygate. To enhance the PM’s power, he wrote into law what Mount describes as a long-held project of the Tory right, egged on by the instinctively authoritarian tabloids. Johnson set about extinguishing all rival sources of power. He got out of the EU; hounded dissident MPs from his party; cowed the civil service by pushing out the cabinet secretary and several permanent secretaries; reduced the power of judges to review the government’s actions; attempted voter suppression by making photo IDs compulsory for voting but not recognizing types of ID that younger anti-Tory voters tend to have; gave government some power over the previously independent Electoral Commission; and gave police more scope to criminalize demonstrations. He pushed much of this package through parliament in spring 2022 while everybody else was obsessing about Partygate.

Even when Caesars are kicked out, they weaken a country’s institutions. They show would-be successors that in every country there is appetite and opportunity for a strongman. They enlarge the boundaries of the possible. Once one Caesar has lied to parliament or attempted a coup, lying and coups lose some of their stigma.

Still, as Mount shows, Caesars are often stopped. To him, the best safeguard is parliament. Worryingly, it has been weakened by decades of derision. Recent approval ratings of the US Congress are 20 percent, and for Britain’s parliament 23 percent.

Mount ends by recounting the ancient ritual by which the door of the Commons is initially slammed in the face of Black Rod, “the major-domo of the House of Lords,” to symbolize the Commons’ independence. Only after Black Rod bangs the rod three times on the door do MPs follow her (the current incumbent is Sarah Clarke) to the Lords for the King’s Speech. Mount concludes: “I used to think that the whole performance was the kind of mummery we didn’t need any more. But now I think we need it more than ever.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.