Summer has arrived. The evenings are warm enough to sit out on the balcony terrace and watch the lights come on in the village below. Each night at ten, the great limestone cliff, into which my little house was built, is floodlit for a couple of hours. On cue two huge baby eagle owls (fully grown wingspan sixty-seven inches) begin rehearsing for adulthood and flap clumsily, then majestically, around the rock, calling for their parents and terrorizing the smaller nesting birds hidden deep within the crags and crevices.

English women wearing broderie anglaise dresses, straw hats and anxious smiles drift about

The annual migration of tourists has begun too. On market day the car parks are full by 9:30 am and the queue for Patricia’s cheese stall is twelve deep. English women wearing white broderie anglaise dresses, straw hats and thin-lipped anxious smiles drift about the stalls while their husbands, red-faced and sweating under Panama hats, look for a table in one of the cafés.

If you want the best goat’s cheese or eggs you have to be there before 8 am. While you’re down there, have a pastis and a coffee with the old men in the hunters’ bar, where twenty years ago a man was, in true operatic style, shot and killed (or wounded, depending on which version you hear), over a love affair.

Second-home owners are here for a few weeks before the school holidays, when they rent out their properties. I manage a few houses and the other day got a message from the son of an owner who was staying, asking if I could visit and investigate a bad smell in one of the bathrooms.

Setting my paintbrushes aside, I walked down to the house. The man, a New Yorker whom I’d met briefly years ago, had arrived the evening before. He opened the door and after I entered, locked it behind me. Strange behavior in a Provençal village. I wasn’t anxious exactly — but I sized him up. He was in his fifties, shorter than me, and didn’t look very strong. I went upstairs. He followed. Yes, the bathroom stank. He couldn’t work out the front door key box and said there was a problem in the second bedroom; the bedside light and fan wouldn’t work at the same time because the extension cable didn’t reach both. I showed him how to work the key box and lifted the bedside table and pulled the cable nearer. “Voilà!”

“I should’ve thought of that,” he said. I was beginning to feel sorry for him. “Jet lag,” I said, and promised to phone a plumber.

On the way back, my mind wandered to the last time I had to properly fight a man off, and although it was unpleasant, it wasn’t without comedy. It was 1992 — I’d had another baby and decided that with two babies under three, dealing with suppurating leg ulcers would be an easier option than the extreme poverty, mental anguish and drug abuse of the acute psychiatric female ward in Glasgow’s East End where I’d been working before maternity leave. A district nursing post came up near home. The work would be less stressful, the commute shorter and I could nip back and feed the baby mid-morning. I applied and was accepted.

A month in, my first patient of the day was a one-legged, wheelchair-bound diabetic man of about seventy. For a week, every morning I was to check his blood sugar, then calculate and administer insulin by subcutaneous injection. On the Friday while checking his notes, I saw it was his birthday. I wished him many happy returns and patted his left shoulder. Mistake. He swung round, grabbed my wrist and pulled me off balance.

I sank into the recliner, sipped a glass of white and waited for the eagle owls’ nightly performance

Being a wheelchair-user, his upper body strength was immense and I had to fight hard to get away. I managed but not before he’d stuck his tongue in my right ear, the memory of which still makes my stomach heave. Before I went home I told the sister in charge. She was a kind, no-nonsense, ex-army nurse and marched straight into the patient’s house and told him if he ever did anything like that again she’d come in on her day off and surgically remove his other leg.

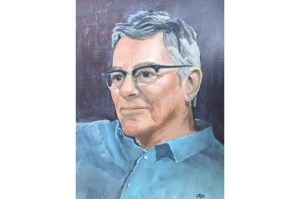

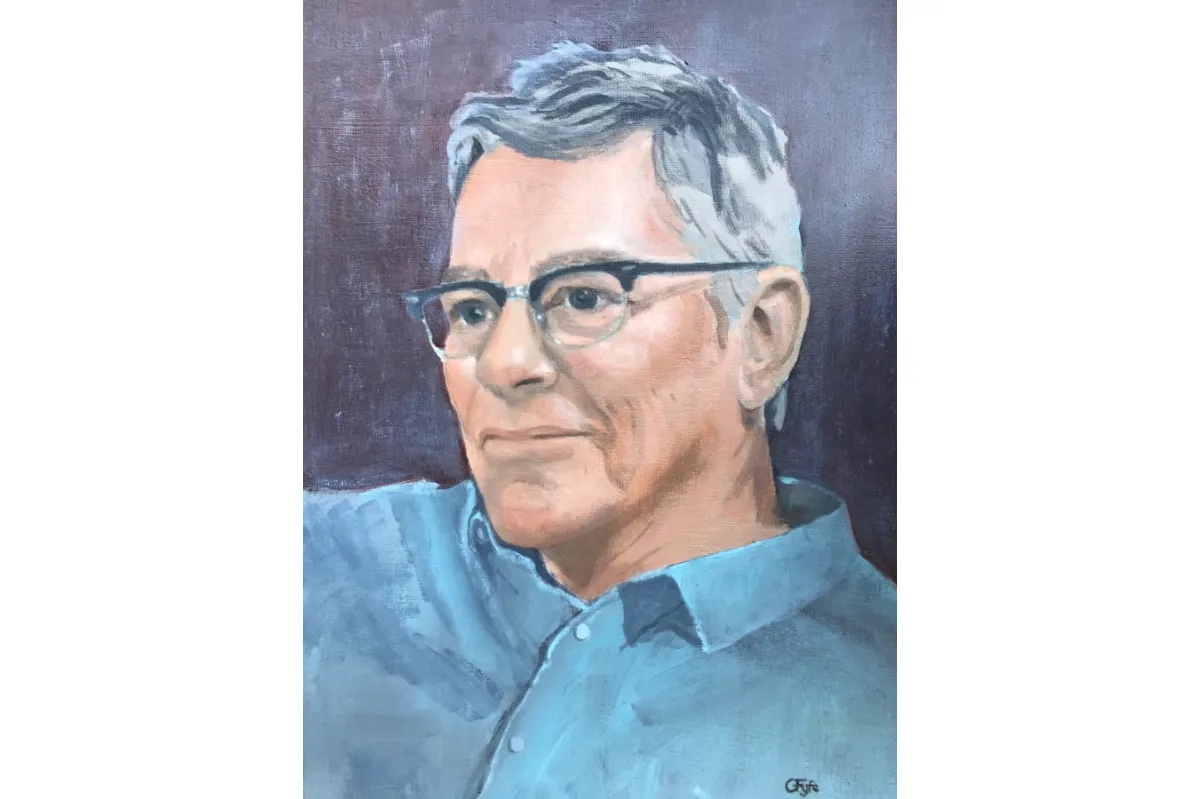

Back in the cave, I picked up the paintbrushes. I have two paintings to finish. The first, “Hyacinth Girl” references Eliot’s poem The Waste Land. I began this in 2022, the centenary of publication, but couldn’t finish it because Jeremy became ill. Last month I agreed to help a Japanese painter friend by sharing exhibition space in the village this summer and must complete it now.

The other work is of my middle daughter standing on a terrace feeding her baby, who in the painting is about the same age (seven months) her mother was when I fought off the creep in the wheelchair.

Later I sank into the Lafuma zero gravity recliner on the terrace, sipped a glass of white Château Roubine réserve, and waited for darkness to fall and the eagle owls’ nightly performance to begin.

Low Life: The Final Years by Jeremy Clarke is out now. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply