I have no doubt that Britain will thrive after leaving the EU, whether or not it leaves with a deal. I say this as a former prime minister of a country, Iceland, which left the EU before it had even joined — and which went on to prosper in a way which would have been impossible had its application for membership been carried through to conclusion. I think Britain can learn from Iceland’s experience and find a way to avoid any major disruption when October 31 comes round.

In late 2008 Iceland suffered especially harshly from the international financial crisis. The country’s banking system experienced a near-total collapse. The value of the currency tumbled, inflation surged, government debt as a percentage of GDP more than tripled in an instant. In 2009, a new government formed by the two parties on the left submitted an application for EU membership. The rationalization offered to the public was that joining the EU was the only way to survive.

Iceland was already a member of the European Economic Area (EEA), which facilitates free trade with the EU. But after the application was submitted, the EU became increasingly stringent regarding the implementation of EU regulations in Iceland. Many of Iceland’s bureaucrats were enthusiastic about obliging.

The elections of 2013, however, brought a halt to accession talks, and in 2015, my government formally withdrew Iceland’s application for EU membership. I had come to the conclusion that withdrawing the application was essential in order for us to be able to make the arrangements necessary for successfully rebuilding the economy.

And bounce back we did. Soon Iceland had the highest GDP growth rate of any developed country. We saw the sharpest fall in government debt achieved by any nation in modern history. Unemployment shrank and, at the same time, we invested heavily in healthcare and other essential services.

Yet the methods we used to bring this remarkable transformation about would not have been possible had we joined the EU and adopted the euro and become bound by EU regulations. Had we done so, our fate would very likely instead have resembled that of Greece.

My government’s decision to withdraw the application for EU membership was, of course, met with hostility from globalists, both foreign and domestic. At every step we were treated to predictions of impending catastrophe very similar to those now being ascribed to Brexit. How odd that adherents of a new global order continue to advocate an international system based on fear and submission rather than reciprocity.

If Iceland, while outside the EU, can achieve the highest level of growth of any western nation so soon after the collapse of its banking system and public finances, then I’m sure that a post-Brexit Britain — the world’s fifth-largest economy — can prosper, too. Nevertheless, there will certainly be some negative short-term consequences from leaving the EU. What can you do to avoid them?

One possible solution is for the UK to become a temporary member of the EEA agreement along with Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein and, of course, the EU. Here the word ‘temporary’ is paramount. It could be for a few years or longer — depending on the time needed to make other arrangements.

By doing so, the UK would be out of the EU at the end of October while still retaining free trade with the EU. You would immediately be able to make new free trade agreements all over the world. Iceland has more free trade agreements than most other countries, including the first such agreement made with China by a European country. In talks on free trade, the UK would be negotiating from a position of strength.

In becoming a member of the EEA, the UK would be joining a system that is already tried and tested. There could be a smooth transition, with no need for a frantic attempt to create a complicated new mechanism in a matter of weeks. Citizens’ rights would be guaranteed while a new framework is developed. And the same goes for trade in goods, services and capital.

What’s more, there would be no hard border in Ireland, just as there is no hard border between Sweden (EU) and Norway (EEA) or Germany (EU) and Switzerland (which has its own bilateral deal with the EU). Luckily, neither the UK nor the Republic of Ireland is a member of Schengen, so there are no problems on that front. And being out of Schengen will allow the UK to protect its other borders, as it does now.

Under the EEA, Britain would immediately be in full control of its fisheries — as Iceland is — and in a position to make its own arrangements for agriculture. Given the size of the UK population compared to its farming sector, any drop in agricultural exports would be more than offset by farmers winning an increased share of domestic consumption.

Admittedly, Britain would still face the burden of implementing some EU regulations while the EEA membership lasts. That would, however, only be a fraction of what the UK has put up with for decades. During the first 20 years of the EEA agreement, Iceland implemented on average around 13 percent of EU regulations each year.

The question is: will this solution be acceptable to the EU? There is no reason why it shouldn’t be. After all, it would be using an instrument of the EU’s own making, because the EEA agreement was originally envisioned as a means of easing reluctant countries into the EU. Some might find it unsettling if the EEA were turned on its head and used to ease a country’s passage out of the EU.

However, the EU is now having to face a democratic decision by one of its members to leave. If the Union’s primary objective in those circumstances turns out to be punishing the citizens of the outgoing country for their decision — even if that means causing great damage to the remaining countries — then it is hardly a great advert for EU membership. If this does turn out to be the case, the sooner Britain leaves, the better. Let the EU do their worst. Britain will do its best and I am sure that will be good enough.

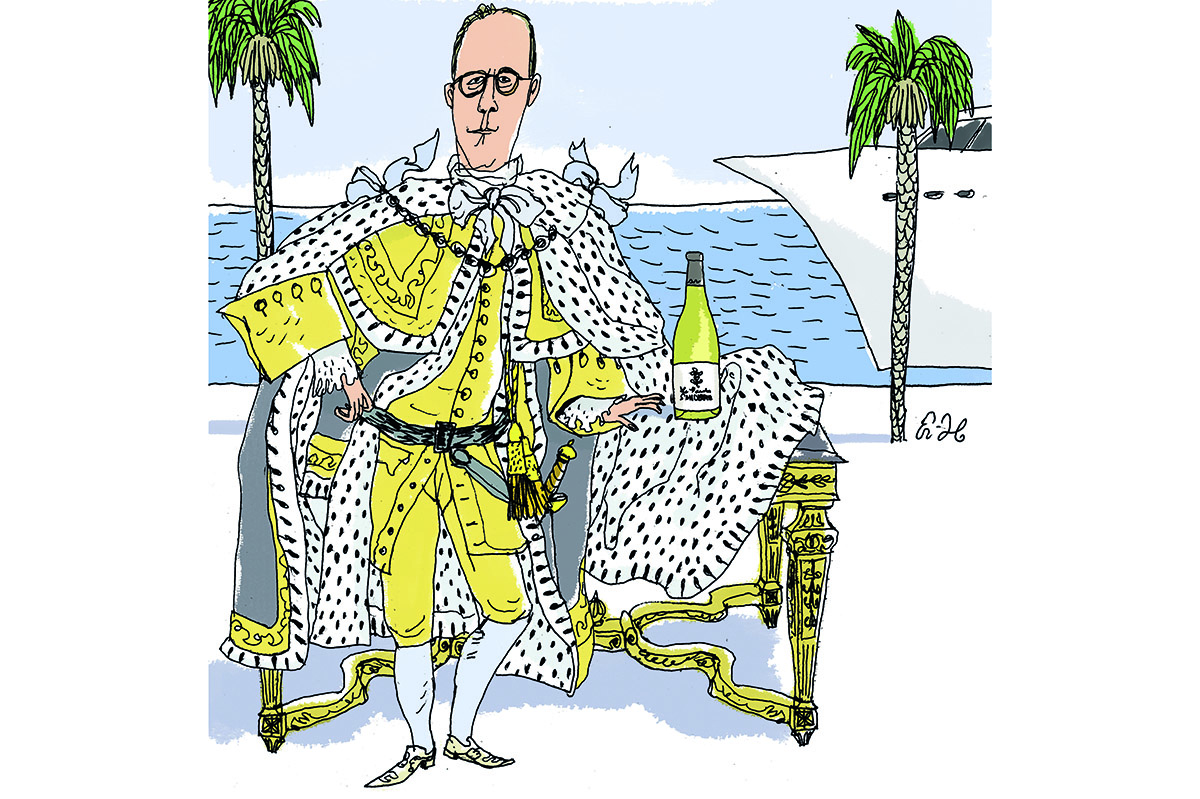

David Gunnlaugsson was Iceland’s prime minister from 2013 to 2016. This article was originally published in The Spectator‘s UK magazine.