It starts with the promise of skipping school — always an illicit thrill at nine years old. My son and I, seasoned truants, hop the early train to downtown Chicago for what I’ve convinced him is a real education. The day’s agenda: two of the city’s iconic museums — grand, intimidating and, up until recently, somewhat sacred.

These sprawling neoclassical behemoths, both originally constructed for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, dot the waterfront like ancient ruins. They once felt like temples to knowledge, where wonder and learning collided, where static displays ignited curiosity. But as we step inside, I can’t shake the feeling that maybe, just maybe, their magic has faded. Can museums as we know them survive my lifetime?

Our first stop is the Museum of Science and Industry. As a child, I adored this place — a shrine to trains, jets, tornadoes and the mechanical wonders of war. It was a place you could turn cranks and pull levers and feel the pulse of human ingenuity. Today, walking down its halls, something feels off.

We pass a gift shop hawking freeze-dried ice cream and “Black Creativity” logowear. Ahead, I spot a series of small rocket models — once the site of an interactive display that let guests launch their own creations. The magic is now gone, replaced by static miniatures.

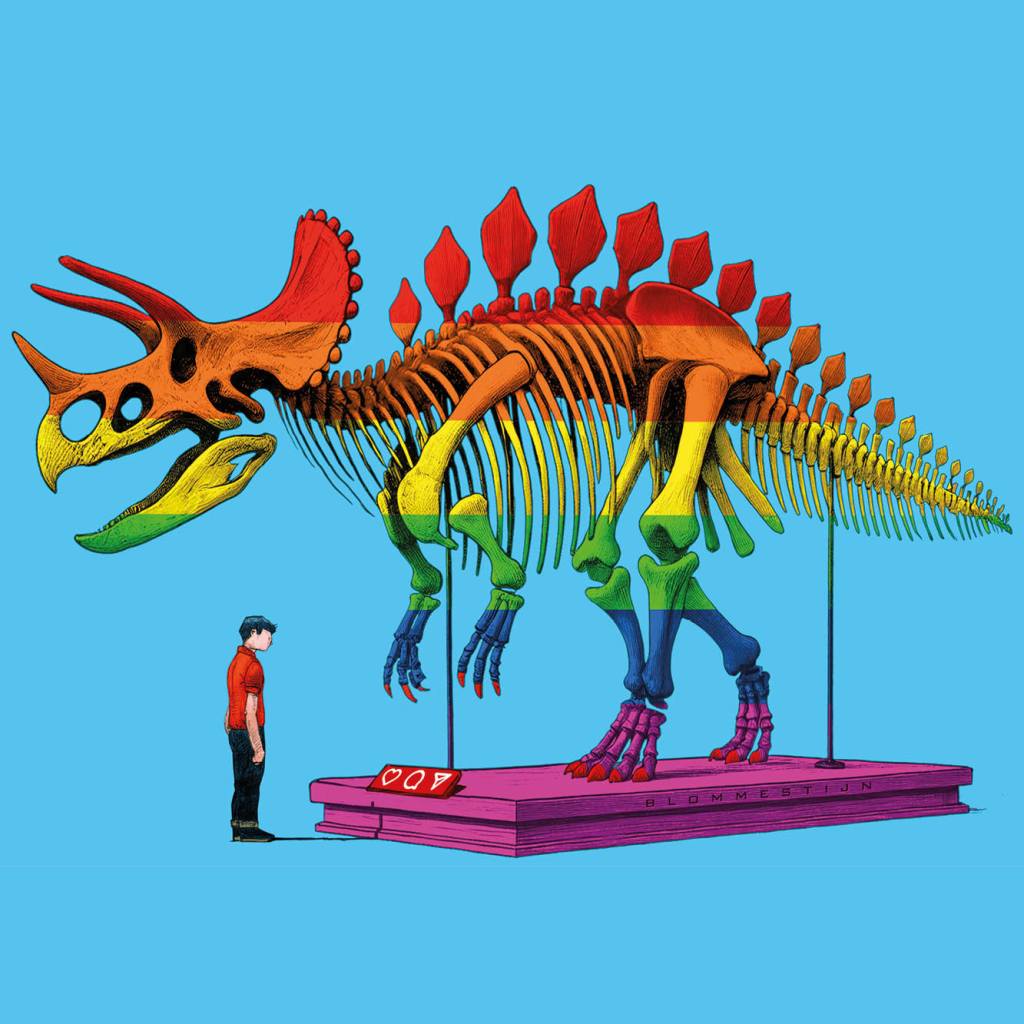

Then, the pièce de résistance: the “career wall” for the next generation of space explorers. Front and center, a picture of a transgender person with rainbow dreads gazes confidently out at the children walking by. The job title? NASA space environmentalist.

What exactly does this person do? I release a chortle and my son is on to me. He asks the million-dollar-question and I struggle for an answer that doesn’t sound like a punchline.

“What is a space environmentalist?”

Likely the reason NASA is subcontracting space exploration, I can’t help but think. Perhaps they’re fighting against the gentrification of Mars. “I honestly don’t know,” I reply.

This is the heart of our modern museums: the drive to inspire has been overtaken by the gratuitous need to moralize. You see it at the Smithsonian’s Museum of American History, where the achievements of the Founding Fathers now come second to lectures on their moral failures, and at the British Museum, where plaques lamenting colonialist guilt outshine the history of ancient civilizations. Even dinosaur exhibits at the Natural History Museum in London now immerse themselves in climate guilt rather than letting us marvel at prehistoric life. It’s no longer enough to present history; we must be instructed on how to feel about it.

I think back to NASA’s golden era — a time of bold exploration, putting human footprints on the moon. Today, NASA seems primarily to worry about carbon footprints.

Museums across the country are shifting from educating to pandering. Take a look at the numbers: in the 1980s, American museums of all sorts were thriving, with over 500 million annual visitors. Their mission was clear — to preserve and display the greatest achievements of human civilization. But since even before the pandemic, attendance has been in steady decline, with some museums reporting decline anywhere from 20 to 35 percent.

My son and I head to the SpaceX Dragon capsule exhibit. This should be awe-inspiring — real, mission-flown hardware, yet the capsule itself feels like an afterthought, buried beneath a barrage of LED screens. The display could easily be mistaken for a Vegas casino floor — flashing lights, flying graphics. I try to point out the capsule to my son, but it’s like shouting into the void. We’re bombarded by low-quality YouTube-style videos playing on endless loops. Whatever awe this artifact might have inspired is drowned out by noise.

There’s no tactile engagement here — no chance to touch, to interact, to fail and try again. No space for wonder. It’s all loud, tasteless high notes without a bit of thoughtfulness. The things that used to make this place magical are gone, replaced by digital entertainment that’s not even good at being entertainment. Museums like MSI aren’t competing with the digital world; they’re poorly imitating it.

I need something less flashy. We head across town to the Field Museum, which I hoped would hold on to some semblance of history. Nestled next to Soldier Field, where it seems an alien spacecraft crashed into an ancient coliseum, the Field Museum stands as a testament to another age — ornate and unapologetically grand, like a Belle Époque train station.

But my hopes were too high. The Native American artifacts, once proudly dis- played, are now shuttered and shrouded. Entire exhibits are shrouded as the museum is the first to comply with new federal guidelines blocking the display of Native artifacts if they don’t have consent from the Indian tribes — erasing any chance to see, let alone learn, from them.

Here, the modern museum doesn’t just pander — it hides. My son peers around the darkened halls, asking what happened. He’s been here before and seen them. I tell him it’s “complicated,” which is parental shorthand for “this is ridiculous.” The idea that we cannot even look at these objects — out of some performative shame — is an affront to the very purpose of museums. I was reminded of that time John Ashcroft hid a too-naked statue of Lady Justice in drapery. This was no less absurd. Museums are meant to preserve heritage, not cower from it.

I remember walking these halls as a child, staring up at the towering skeleton of Sue the T-Rex or marveling at the intricate dioramas that brought ancient cultures to life. Today’s museum feels more like a tacky amusement park. At every turn, we’re confronted with a 4D virtual-reality ride or a VR game promising “education” but delivering little more than pixelated nonsense. We cave, trying a VR “shark attack” experience, only to find that it looks like a 2001 video game.

When we leave, I’m exhausted — not physically, but mentally. The popularity of “interactive experiences” like the Van Gogh Experience or the Museum of Ice Cream is emblematic of a larger trend that has shoved real museums into the land of Instagram ads. They hope to ride a wave and capture some fleeting, attention-challenged eyeballs. They’re failing. These museums are the worst of both worlds and it’s tragic.

What, then, is the role of a museum in a world where kids carry the internet in their pockets?

I still believe museums can offer something profoundly different. Rather than competing with TikTok or YouTube, they should be their antidote — a place where the noise of the digital world fades and we’re left to confront history, science and art at full scale. Not as soundbites or flashing images, but as tangible artifacts.

Museums, after all, were once guardians of our collective memory. The very word comes from the Greek mouseion, a place dedicated to the Muses — the goddesses of the arts and sciences. The first mouseion, established in Alexandria in the third century BC, was home to the famous library — a place where scholars didn’t just preserve knowledge, they expanded it.

By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, museums had evolved into public institutions, democratizing access to art and history once reserved for the elite. They were places of quiet reverence, where one could stand before the brushstrokes of Rembrandt, the chiseled form of a Greek statue, or the meticulous craftsmanship of an ancient manuscript. These institutions invited contemplation, not consumption.

As the train rumbles back toward home, our bellies full of Shake Shack, my son asks when we can play hooky again and visit another museum. I’m sure we will — nostalgia has a way of softening disappointment. But I can’t help but wonder: what will be left for him to experience when he’s grown? Will museums offer something grand or will they become just another screen in an endless sea of distractions?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply