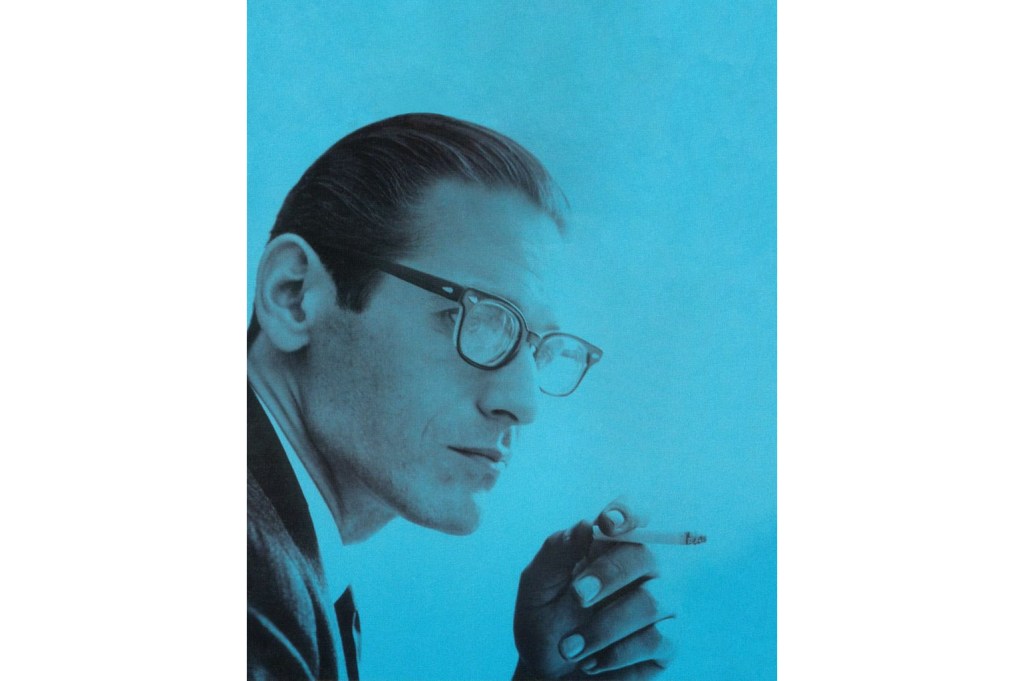

Everybody Digs Bill Evans was the title of one of the great jazz pianist’s early albums, but it wasn’t always clear that he dug himself, at least if you consider his turbulent personal life. There was, first and foremost, the lifelong drug habit, culminating in his death in 1980, which one friend deemed the ‘longest suicide note in history’. There was also the introspective streak that prompted Evans to doubt his own prowess even after he had become famous. But there is also the spellbinding music that casts as powerful a spell as ever.

Small wonder that a cluster of purveyors of fine music, including Craft Records, Electric Recording Company and Acoustic Sounds, have rushed to reissue his works on CD and LP. In a musical genre that has often favored the ebullient performer, Evans offered a diffident contrast. Here was a grandmaster who shunned grandeur. He specialized in the trio, that most demanding of art forms, to communicate his intensely contemplative inner vision by introducing modal inflections and tone chords, among other things, to jazz. He never cut corners and only delivered brilliant ones.

After he recorded his first LP for Riverside Records, New Jazz Conceptions, in 1956, Evans didn’t produce a new one for another two years, stating that he ‘didn’t have anything particularly different to say’. But he soon made a profound difference in the jazz world. Once he hit his stride, so to speak, Evans never looked back. An unfailingly elegant performer, his lithe ensemble work and inventive solos pushed jazz forward in a new direction, one that drew its intellectual and emotional resources, its very sustenance, from European classical traditions that were anathema to more than a few of his contemporaries.

Evans, who was born on the eve of the Great Depression in August 1929, imbibed those traditions growing up in New Jersey. He studied the violin, piccolo, flute and piano, playing Mozart, Schubert and Beethoven. Studies at Southeastern Louisiana College on a flute scholarship and the Mannes School of Music in New York immensely aided his grasp of music theory, which he put to use in crafting compositions such as the famous ‘Waltz for Debby’ (named for his niece), which also served as the title for a live album recorded at the Village Vanguard in 1961 with the drummer Paul Motian and the bassist Scott LaFaro.

The turning point for Evans arrived when he replaced Red Garland in Miles Davis’s band in April 1958. This was no stormy weather for Evans, but a welcome haven in which to explore a new harmonic world. Davis was captivated. ‘Bill had this quiet fire that I loved on piano,’ Miles recalled. ‘The way he approached it, the sound he got was like crystal notes or sparkling water cascading down from some clear waterfall. I had to change the way the band sounded again for Bill’s style by playing different tunes, softer ones at first.’

The result was Kind of Blue, the legendary album recorded at Columbia studios in 1959, featuring an all-star cast of Davis, Evans, Cannonball Adderley, John Coltrane, Paul Chambers and Jimmy Cobb, that moved away from hard bop toward a modal approach.

Evans went on to record notable efforts with his own bands. Craft’s lavish tribute to Evans features five CDs with over 60 tracks from his work for Riverside, Milestone, Fantasy and Verve, as well as a previously unreleased live concert from 1975, not to mention a 48-page hardcover book containing extensive liner notes and photos. The vinyl reissue impresario Chad Kassem of Acoustic Sounds is offering all of Evans’s Riverside recordings on 45rpm vinyl. And the Electric Recording Company, which is based in London, has specially pressed an LP of Portrait In Jazz.

These multifarious reissues testify to Evans’s enduring popularity. One of the best is Interplay, which was released by Riverside in 1963. Its unusually dynamic tracks, such as ‘You and the Night Music’ on which Philly Joe Jones’s thunderous drumming is beyond reproach, it shows another side of Evans. Clearly he could lay down the law as well as soar into the empyrean.

As rock music replaced jazz as a popular idiom, performers such as Miles Davis drifted towards an ill-fated romance with a musical excrescence known as jazz fusion. Wynton Marsalis once remarked that his greatest disappointment was the implosion of Davis. Evans followed a more stringent path. He never compromised his artistry but remained dedicated to exploring the musical frontiers of jazz. His performance, recorded by Verve in February 1966, at Town Hall shows him at the top of his game. Another gem freshly unearthed by Craft is a double-LP called On A Friday Evening, a recording of a concert by Evans that took place on June 20, 1975 at Oil Can Harry’s in Vancouver. No matter his personal woes, Evans almost always vouchsafed his listeners something not merely to dig but to cherish.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2021 World edition.