On Independence Day, Americans recall not only the ideals that led to the founding of the United States, but the sacrifices of those who have made our unique experiment into an ongoing reality.

Recognizing the challenges that affect many who have been in the military, CreatiVets, founded in 2013, provides help to disabled veterans through engagement with the arts. Program participants learn how to address and share their experiences through studio arts, music, songwriting and creative writing. The organization’s goal is to help these veterans “transform their stories of trauma and struggle into an art form that can inspire and motivate continued healing.”

I recently spoke with CreatiVets’s art director Tim Brown, social media coordinator Elizabeth Huefner and deputy director Kyle Yepsen to talk about how they put this into practice.

As you might expect, CreatiVets’s location provides many opportunities for participants to engage with music, and music is by far the most popular. Yet from the beginning, visual arts have also been important: After he was wounded in Iraq, CreatiVets’s founder Richard Casper credited his art classes at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, particularly in ceramics, for saving his life from post-traumatic stress and depression.

Ceramic art has also proven to be a helpful entry point for many CreatiVets participants. “Ceramics tends to be in our nature as humans, to be playing with earth,” says Brown. “It’s not like sitting someone down in front of a canvas or a piece of paper and asking them to come up with an image about what’s going on in their minds. With ceramics, you can put clay in front of someone and just have a conversation with them while they’re playing around with it. And almost before they know it, they’ve created something. We’ve found it the easiest way to get some folks to open up.”

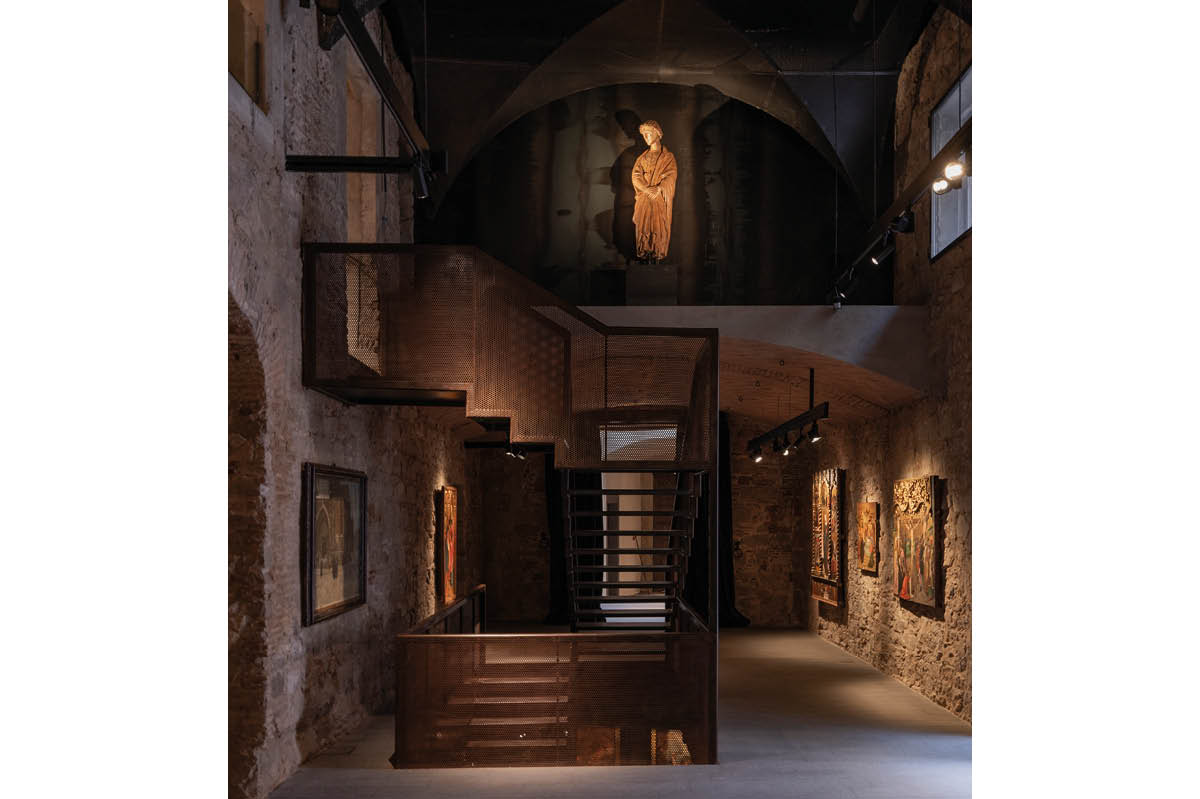

Programs include a wide variety of media, from painting and photography to metalwork and sewing. In addition to its long-standing partnership with the Art Institute of Chicago, CreatiVets partners with the Glassell School of Art in Houston and Belmont University in Nashville; it’s always looking for more art institutions to work with. Program participants are transported, housed and fed by the organization at no cost, especially important since many are taking a step into the unknown.

“We’ve had people come to the programs who haven’t left their home in years,” Brown notes. “So to get out of their house, get on an airplane and go study art on a college campus can be a little overwhelming.” Yet the programs, which typically last from two to three weeks, can have a profoundly positive effect on the participants straightaway, Brown finds.

“I’ve noticed so many times that after they start,” says Brown, “the vets get so excited and ask, ‘So how do I work this into my project?’ Then they learn something else and ask, ‘How do I combine this into my project?’ It’s really fun to see how ramped up everybody gets. They just have to get through the door.”

“We really want to help them to tell their story,” Kyle Yepsen says. “That’s the biggest part, telling their story in a way that doesn’t require them to talk to strangers or be so vulnerable in front of people that they feel like they can’t do it. We want them to continue to create art and tell their stories.”

Part of that storytelling involves being able to display and share the works that they create in a group show, which can reflect some amazing personal transformations.

“We had [veterans] come through the program who, at the beginning, didn’t want to talk about anything,” Brown recalls. “But by the end, you see them standing in the middle of the gallery, talking about their work, excited to share it with anyone who wanted to come through and ask questions. It’s just such a phenomenal behavioral change.”

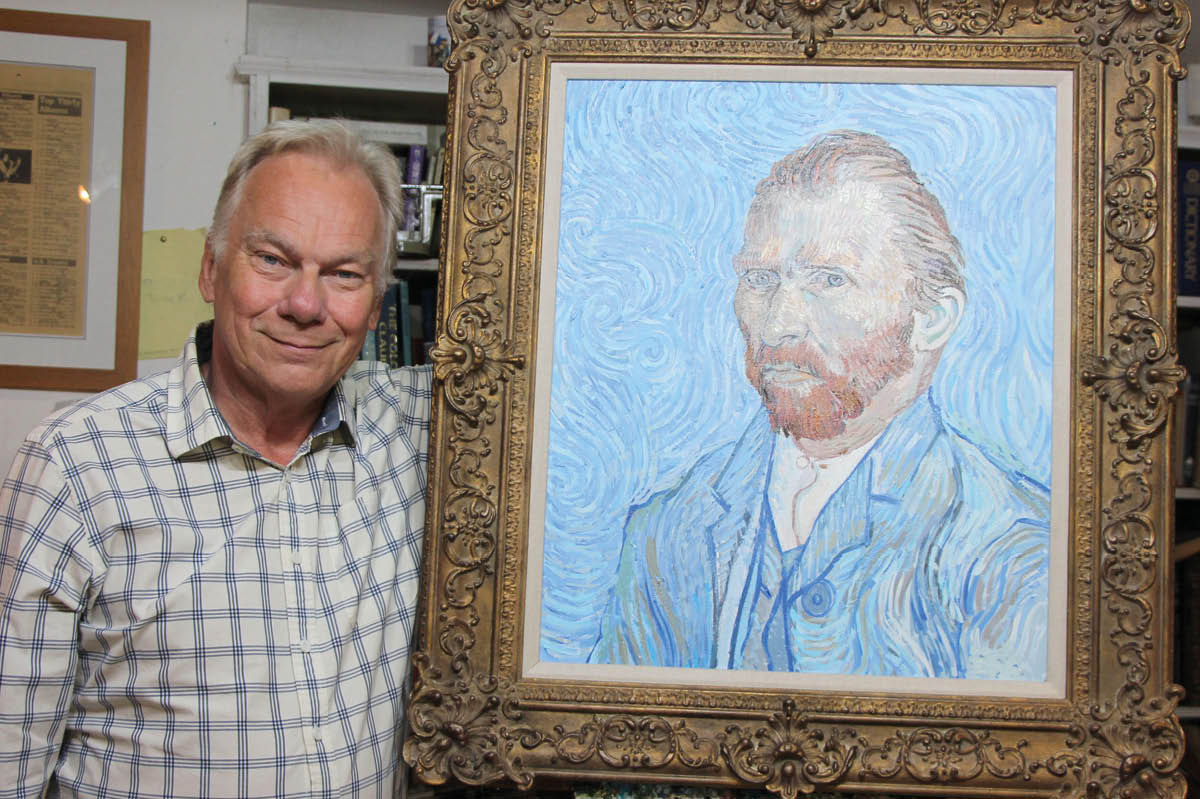

This therapeutic aspect of creating art has been observed, and indeed experienced, by CreatiVets staff as well. Brown, himself both an artist and a distinguished combat veteran who served tours in Afghanistan and Iraq, understands on a personal level.

“We’ve had so many success stories. For example, these vets might still experience combat nightmares,” Brown says, “but after the program they’re not having them every night. It’s the little successes that can make a big difference. Just working with this organization has been therapeutic even for me, and dealing with my own combat time, as it has for many who have worked with us. We’re all very passionate about how art can help, because we see the value of it every single day.”

Participants come from a variety of levels of artistic experience, but the majority have none at all. While occasionally a participant may already have a passion for a particular field, most do not currently have any creative outlets. And some end up doing something completely different from whatever they had been pursuing previously.

“Ahead of time, we question them about the things they’re doing,” Brown explains. “If they’ve done music, they try the art programs. If they’ve done art, they try music. The point is that maybe the outlet they have right now isn’t as effective as they want it to be, and trying something different may help.”

Building community plays a significant role as well. “One of the biggest pieces of our programs,” explains Yepsen, “is that we always have veteran mentors.” Past participants are paired with new ones. “We really try to tailor this mentor relationship with individual veterans — if you were a Marine who served in Iraq post-9/11, we’ll try to find you a mentor-alumnus who has a similar service history.

“One of the biggest benefits from being connected with the veteran community,” Yepsen notes, “is that we do get contacted by people who say, ‘Hey, my friend is not doing well, and I think they would benefit from one of your programs: can you help them?’ And we reach out and see what we can do by getting them involved as quickly as possible.”

Elizabeth Huefner recounts the story of an art-program participant whose friend, an alumnus, put him in touch with the organization a few years ago. “This guy was thinking, ‘All right, I’ll go out there, and do all of this artsy-fartsy stuff for a few weeks, and then I’ll go back home and blow my brains out.’ He was very suicidal. Then he came through the art program, and today he’s our veterans outreach coordinator.”

Sharing personal experiences with potential participants, who are often skeptical, creates a personal connection before the participant even arrives. The organization also provides guidance to those who discover that they may want to pursue the arts at a professional level.

“We have a separate program for people who actually want to pursue a creative career,” says Huefner, who has recently begun working with female veterans on music instruction. Among other possibilities, alumni may enroll at discounted rates at the art institution where they’ve studied. Adds Yepsen, “One of the benefits that we have is in providing smaller-sized classes, where there are maybe eight to ten veteran students. They can develop an intimate relationship with the university and the university instructors, so that if they do have an interest in going [on], we can help them with making those connections.”

Past participants are brought back not only as mentors but as teaching assistants to help both students and instructors. “The class is still led by the university professor or instructor,” Yepsen explains, “but the program alums are there, too. They stay on campus with the veterans, so that if somebody has a trigger at two o’clock in the morning, they can walk down the hall and knock on their mentor’s door. And we bring them back not only so that they can help in the classroom and outside of it, but so they can also further explore their own artistic interests.” This gives alumni a second opportunity to work with the educational institution — one came to the program with no artistic experience at all and is now a professional photographer. Another has paintings represented in regional galleries: both come back to mentor and instruct.

“We’re not suggesting that art is something these vets have to take away and try doing for the rest of their lives,” Brown says, “but they always keep up with each other, and there’s always a handful in every class that become practically inseparable. A lot of our alumni are still talking to each other on the phone, or meeting up when they’re in the same city. The community that we’ve built within the programming we offer is so vital to their continuing to reach out, stay active and tell their story.”

Yepsen sees the organization as part of the “American agreement.”

“Part of being Americans is that we have a role to play in the world. We all say, ‘Respect the troops,’ and ‘Thank you for your service,’ but this is that next step. I think it’s a requirement for Americans to make sure that men and women who volunteered, when they need something, it’s our job to step up and say, ‘This is our part of the American agreement that we all have with each other, and we’re going to take care of you.’”

“Kyle and I are both civilians,” agrees Huefner, “and personally I have no military family or background. I’ve always been patriotic and appreciative of what our military does and the sacrifices they make. But there just aren’t enough things in place to help, or to reach so many people coming back with so many problems.” To address this, she says, the organization is starting chapters around the country to connect veterans, even for something as simple as a regular cup of coffee.

“The biggest benefit of having these community groups,” adds Brown, “is that if they know [someone] who is struggling, they can reach out and talk to them, and then someone at a chapter level can come to us to see if our programming can help. If we can build these communities, we can try to address that by reaching more people.

“Knowing how much of an impact this programming has made on individual vets, and being able to bring that to someone else,” Brown concludes, “and watch them connect through something like art, and to be a part of it… Maybe this is just a small group, but it’s such an important one.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply