What is there left to say about Picasso? This question, posed by a colleague apropos of Picasso: Painting the Blue Period, an exhibition on display at the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, is inevitable. There are few cultural figures whose life and accomplishments have been as exhaustively accounted for as the man born — take a breath! — Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso. Innumerable exhibitions, books, scholarly tracts and films have been devoted to this relentlessly protean artist. Even after his death almost fifty years ago — Picasso died in 1973 at the age of ninety-one — he looms large in the public consciousness. Picasso’s stature in the upper echelons of the art world has, admittedly, been somewhat diminishedby the promotion of Marcel Duchamp and his nose-thumbing progeny. Feminists have taken umbrage at the lionization of Picasso maltratador — which is how he was described last year at Barcelona’s Picasso Museum by a group of students protesting his treatment of women. Certainly, there are few artists less amenable to the unforgiving puritanism of our professional classes.

I mean, what might the woke-adjacent make of the subtext undergirding Painting the Blue Period — that Picasso was a socially conscious individual, an artist acutely aware of his proletarian status and an ally of the poor and the homeless, the underserved, incarcerated and marginalized? In late 1901, Picasso began visiting the Saint-Lazare women’s prison near Montmartre under the offices of Louis Jullien, the facility’s resident doctor and a specialist in venereal diseases. (Dr. Jullien went so far as to forge a medical identity for Picasso so that he could roam the grounds unaccompanied.) The young artist was, we are told, moved by “the struggles faced by poor women and their children in the modern world.” Twenty-first century sophisticates will snigger at this attempt to humanize Pablo the Perpetual Misogynist. And it is worth recalling the story, as related in John Richardson’s four-volume biography of the artist, that Picasso extolled the “models” at Saint-Lazare because they cost him not a centime. Still, human nature is nothing if not contradictory. The rest of us are defined by motives, ignoble and otherwise. Why not extend the benefit of a doubt to Picasso?

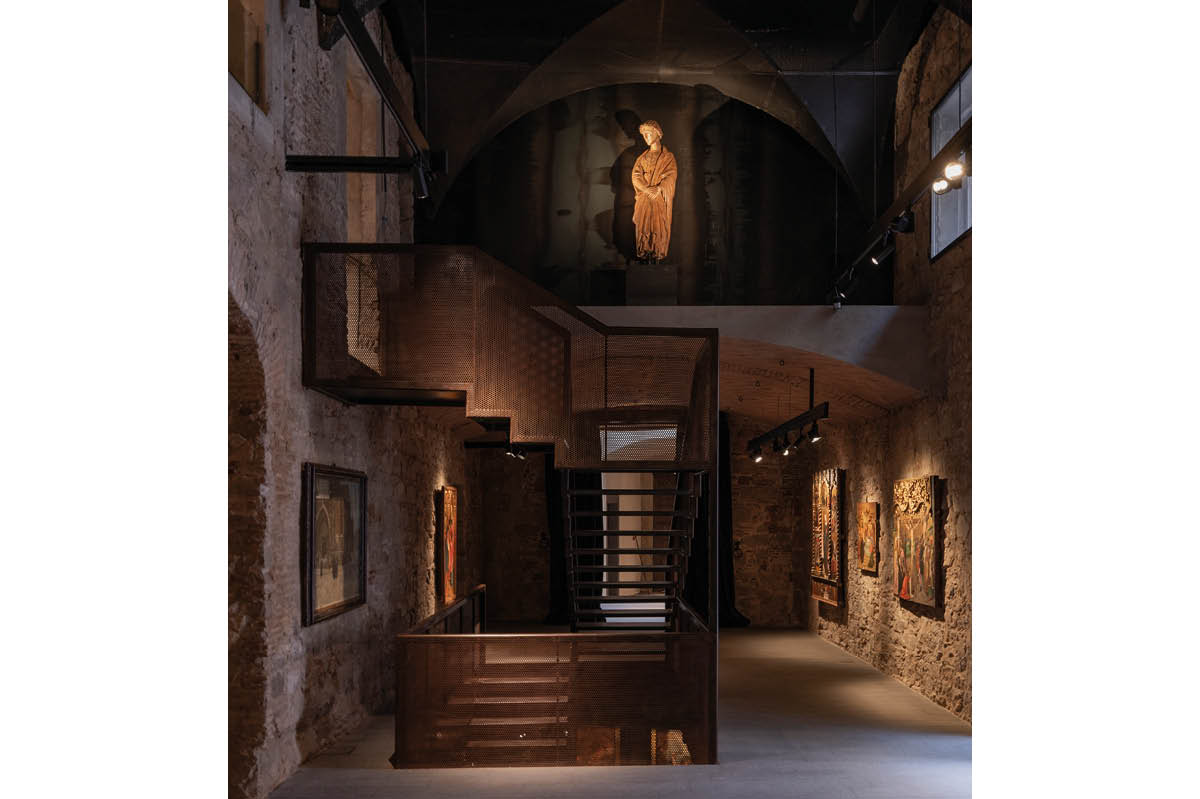

Truth to tell, the organizers of Painting the Blue Period have little truck with the soundness of Picasso’s moral probity. Co-curators Kenneth Brummel of the Art Gallery of Ontario and Susan Behrends Frank, associate curator of research at the Phillips, are interested in Picasso as — dare one say it? — an artist. Turns out that Brummel and Frank actually like art. Among the blessings of the exhibition is the absence of political posturing — guilt-mongering, really — that is all but de rigueur for curators nowadays. Instead, visitors learn how a given drawing, painting, sculpture or print was influenced by Picasso’s immediate environment or a particular motif (whether sacred or profane), and how it was realized through the accumulation of graphite, charcoal or oil paint. A significant part of the exhibition is, in fact, given over to process, conservation and scientific analysis. Three canvases — “The Soup” (1903), “Crouching Beggarwoman” (1902), and the Phillips’s own “Blue Room” (1901) — were subject to a variety of intensive imaging techniques. Painting aficionados will relish the opportunity to see X-ray photographs displaying how Picasso recycled canvases and imagery. Discovering how he upended a landscape painting and morphed it into “Crouching Beggarwoman” provides an especially telling sidebar. At the age of twenty-one, Picasso was already attuned to the power and possibilities of transformation.

Which isn’t to say that Painting the Blue Period highlights a kingpin of the avant-garde. The artist whose radical innovations would reshape the traditions of painting and sculpture? He ain’t here. What we have is Picasso at his most — well, let’s not say “derivative.” Having left Spain in 1901, Picasso traveled to Paris, settling in a studio a stone’s throw from the Moulin Rouge. He shared the apartment (if not the expenses) with his agent Pere Mañach, a transplant from Barcelona and scion of a family of industrialists. “Self-Portrait (Yo)” (1901) — a hardscrabble picture done on cardboard — evinces a man of chiseled good looks and unwavering confidence, a temperament out to make a name for itself in the demi-monde. That, and it divulges a proud reliance on the stylistic mannerisms of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Lautrec died just a few months after Picasso’s arrival in France; from all accounts, the two never met. But Lautrec’s example weighed significantly on Picasso. He adopted many of the older artist’s subjects — cabarets, cafés and brothels — as well as the lifestyle attendant to them. “Catcalls and Capers” and “Lures for Men” (both 1901), comic illustrations Picasso did for the magazine Le Frou-Frou, could be touted as Lautrecs and few people would blink an eye.

Lautrec himself makes an appearance in Painting the Blue Period: his efflorescent “May Milton” (1895), a mixed-media depiction of the English dancer, is hung adjacent to “Catcalls and Capers” and “Lures for Men.” By placing these works in close proximity, Brummel and Frank underscore Picasso’s preternatural ability to absorb and integrate influences. Throughout the exhibition, Picasso’s efforts in oil, graphite, charcoal and bronze — including “Seated Woman” (1902), his first attempt at sculpture — are juxtaposed with works by historical figures, as well as those of artists within his milieu. “Nude Woman Standing, Drying Herself” (1891-92), a lithograph by Edgar Degas, and two sculptures by Auguste Rodin, “Eve” (c. 1881) and “Crouching Woman” (1880-82), are set alongside Picasso’s early explorations into the expressive potential ofthe female form. Elsewhere, Honoré Daumier, Édouard Vuillard, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Luis de Morales and El Greco amplify Picasso’s work in revelatory ways flummoxing ways, too. Who would consider mashing-up Puvis de Chavannes’s arid neoclassicism with the decorative contouring of Vuillard? It’s an endeavor that would strain most imaginations. But imagine Picasso most surely did, particularly with “The Soup.”

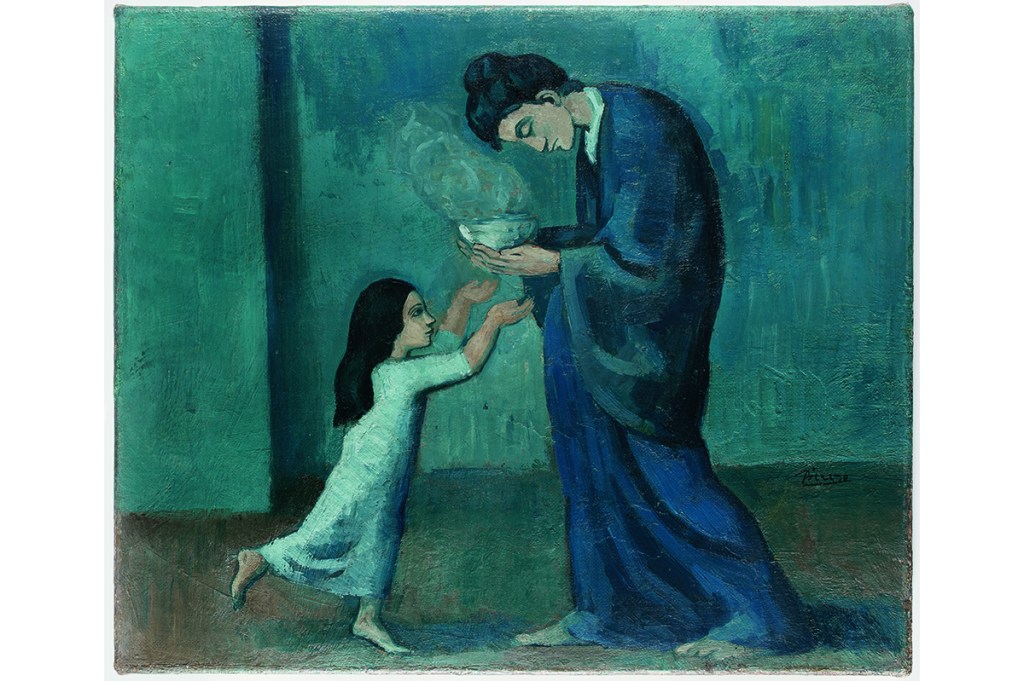

The gallery devoted to “The Soup” is among the most gratifying museum installations in recent memory. Brummel and Frank, with tremendous scholarly acumen and no little sense of nuance, set out the genesis of a simple image — a mother providing a bowl of soup for her daughter — and prove just how complex it is. Painted during a return trip to Spain, “The Soup” revisits a motif Picasso had touched on before: motherhood and poverty. Whereas “Science and Charity” (1897) — an earlier painting not included in the exhibition — was couched in nineteenth-century convention, “The Soup” is startlingly modern, if not strictly speaking Modernist. Writing in the catalogue, Brummel describes it as a “pictorial settlement” between Daumier and Puvis de Chavannes. That’s putting it mildly. What Picasso does is streamline Daumier’s muscular caricatures and bypass Puvis de Chavannes’s Hellenism to channel Third Dynasty Egypt. The accompanying studies on display — done in pastel, oil and ink — testify to the tenacity, grit and gravity with which he approached the picture.

The upshot is a painting whose modest scale can’t contain the monumentality of its forms. In point of comparison, the smattering of pieces that close the exhibition — presaging, as they do, the Rose Period — is small beer. Then again, some respite is in order after the intensity of mood that dominates Painting the Blue Period. It’s a great exhibition.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2022 World edition.