Rock music is always so close to parody that the best and best known fictional film about a rock tour is This Is Spinal Tap. Rolling Thunder Revue, new on Netflix, is a rock documentary — a rockumentary, if you will — about Bob Dylan’s ‘Rolling Thunder’ tour of December 1975. Its producer is Martin Scorsese, who made The Last Waltz in 1976, when rockumentaries had yet to become mockumentaries by default.

Really, it was the musicians who made The Last Waltz, and Scorsese who turned that material into not just one of the best concert films, but also a sharp-eyed study of musicians and the music business. In Rolling Thunder Revue, we see both sides now, and then some: a concert film of a ferocious Dylan with a terrific band, a coke-flecked anatomy of the mid-Seventies music business, and a sense of how, while Dylan led a caravan around recession-struck New England towns, the United States was approaching its Bicentennial as a house divided.

In 1974, Dylan had toured for the first time since falling off his motorbike in 1966. The tracks of the stadium circuit began to be laid in 1966. The Beatles had shown the gigantism that was the future of the business when they played the first stadium show in 1965, at Shea Stadium. Dylan’s reunion with The Band in 1974 was a cash-in that produced a cokey, heavy-handed live album, After the Flood. His marriage ended after the tour, eliciting the new peak of Blood on the Tracks.

Dylan conceived of Rolling Thunder as an anti-tour, the opposite of what the Seventies’ rock business had become, a ‘conman carny medicine show’ in Allen Ginsberg’s words, a revival of the Old West in the decaying East. Dylan compiled the bill, enlisting Rambling Jack Elliott, Ginsberg and Joan Baez. He drove his own bus, directed the tour to small towns and small halls, and made sure to use a small and inexperienced promoters, one of them a reformed fishmonger. But it turned into a tour like most others — wild, shattering, and struggling to make money.

Here, in his first extensive interview for years, Dylan remains evasive as ever, and Scorsese, who seems to have drifted into a complacent dotage, plays along. The name ‘Rolling Thunder’ came from the weather, but it was also the name of the bombing operation of Vietnam and, Dylan says, a Native American phrase meaning ‘speak the truth’. The white face-paint Dylan wore was inspired by commedia dell’arte, with a bit Japanese kabuki, or was it because Dylan had seen Kiss? The tour footage is supposed to have been the work of Stefan van Dorp, but he is a fictional character, played by Bette Midler’s husband. We are being spoofed. How funny.

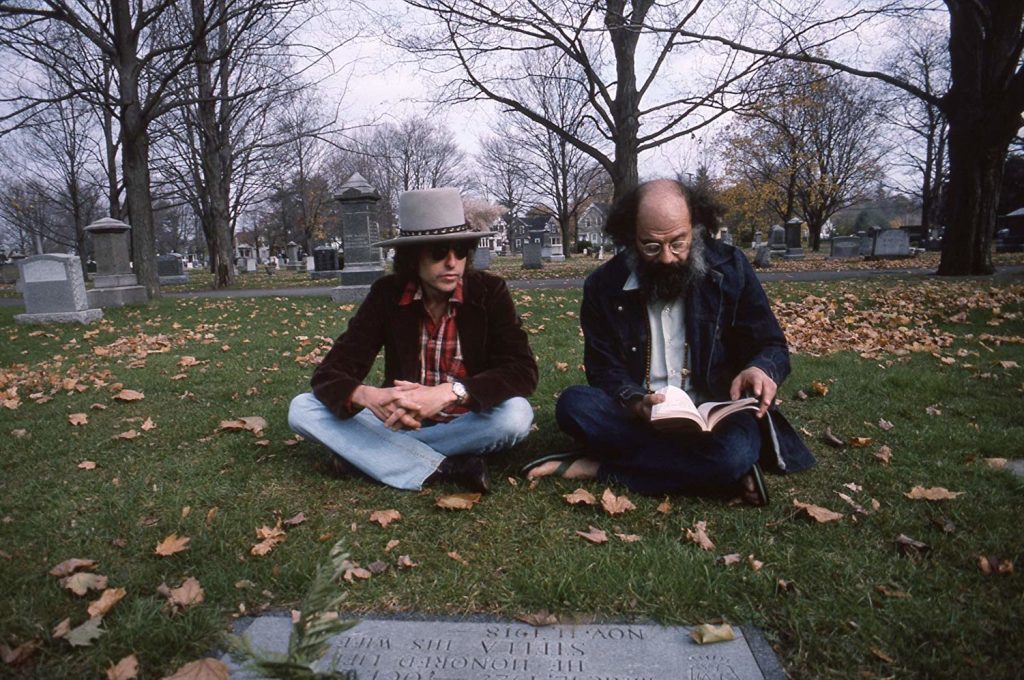

It’s not clear what we gain from the foolery, and anyway, none of it comes close to Spinal Tap. The truth is that most of the acts on the Rolling Thunder tour now seem boring. Patti Smith claps on the offbeat, and artily refusing to shift to the onbeat even though her audience, more competent than her, are on the two and four. The gaseous Allen Ginsberg dives in front of the camera to parp out a stanza. Joan Baez sings exhortingly and dances execrably. Roger McGuinn does a nose-bugling, eye-bulging turn, though, and we get to see Dylan and Ginsberg at Kerouac’s grave at Lowell, Mass., and Joni Mitchell testing out ‘Coyote’, with Dylan trying and failing to keep up with her chording.

Dylan, meanwhile, is on fire, or perhaps just on cocaine, which the performers are alleged to have been paid in. We see the greatest American lyricist since Richard Rodgers tearing into the words, roaring and sneering behind the band that he would record Desire with the following year. The live performances make the rockumentary worthwhile, even though the mockumentary elements are annoying, and undercut the often stunning live clips. As Marty di Bergi the starstruck producer says in Spinal Tap, ‘Don’t look for it, it’s not there any more.’

Dominic Green is Life & Arts Editor of Spectator USA.