This is the second excellent book by Benjamin Balint to consider the cross-cultural perils of being a great writer after you’re dead. His first, Kafka’s Last Trial: The Case of a Literary Legacy, described legal battles over the residence of Kafka’s literary estate. This new one shifts the focus to a very different (and equally unusual) writer, Bruno Schulz, whose work has long been caught up in posthumous conflicts about who it most belongs to — that motley assembly of us selfish readers who actually read him, or those various governments competing to claim him as part of their national heritage.

Born in 1892 in the wildly multicultural and polyglot Drohobych, Schulz grew up in a home “dominated by women.” His parents owned a textile store on the market square, and when Schulz wasn’t being adored by his mother, or ordered about by his much older sister, he played among scraps of cloth and trimmings, and imagined stories behind the facades of the silently looming mannequins, while the shadow of his broody father came and went (as he later would in Schulz’s fiction) like a Blakean demi-god, full of dark mutterings and forebodings. Schulz would eventually romanticize his childhood memories with all the power of a born storyteller — for it seemed that only by telling stories about the world could he acquire any control over it. “The most beautiful and most intimate thing in a man,” he once said, “are his memories from youth, from childhood.”

Schulz grew up amid an effervescent tapestry of languages, cultures and nationalisms in what Balint describes as:

One and a half cities: half Polish (the gentry), half Jewish (the merchants), and half Ukrainian (the peasantry). Its streets resounded with mixtures of Polish, Ukrainian, German and Yiddish. During Schulz’s childhood, more than 40 percent of the town’s inhabitants were Jews, some 30 percent Catholic Poles, and 30 percent Ukrainians. By decades-long tradition, Drohobycz was administered by a Catholic Polish mayor and a Jewish vice mayor. Some 80 percent of the employees and managers in the city’s oil refineries were Jews. It was rumored of one of the wealthiest of the Drohobycz “oil kings,” Moses Gartenberg, that wherever he threw his yarmulke he would find a deposit of black gold.

As a young man, Schulz traveled, but always (and ultimately) returned to his home town, where he taught himself to paint by sitting in the park every afternoon. He then went on to teach art at the same high school from which he had graduated. He suffered from depressions and unsuccessful romances, felt increasingly restricted by the school calendar, and was later remembered by students as both an awkward man who entertained them with improvisatory fairy tales, and as one who never quite concealed his masochistic desires to be hurt by attractive, long-legged women. (One student recalled him coming to school carrying a whip under his coat.)

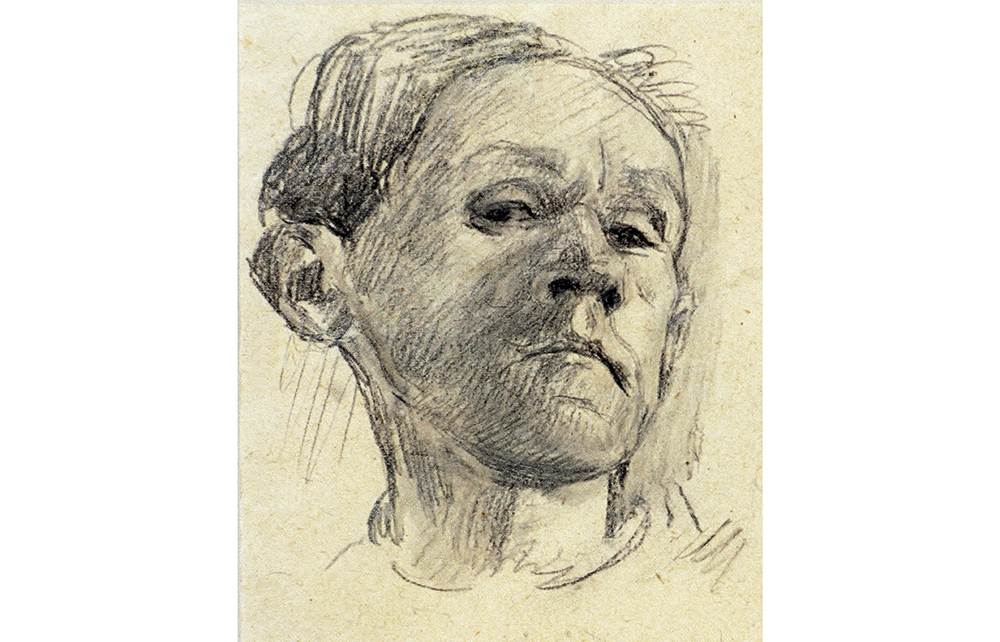

These fantasies were explored in many of his early drawings and paintings, which carried titles such as “Girl with a Briefcase Stepping on a Prostrate Man” and “Maid Flogging a Naked Man with a Birch Whip.” His pictures were lush, rich, exotic and otherworldly, expressing the unconcealed desires of a man for pleasures he didn’t quite understand. One of his most devoted readers, the great short story writer Isaac Bashevis Singer, once commented: “When you look at his picture you see the face of a man who never made peace with life.” But it might also be said that when you look at one of Schulz’s drawings or read one of his stories, you share the lucid dreams of a man who had definitely made peace with art.

He enjoyed great fame for his early work — especially upon publication of the first (and best) of his two collections, Cinnamon Shops (1934), (later translated into English as The Street of Crocodiles). These luminous stories explored an intimate private realm of mothers, sisters and maids, swirling gradually outwards into wider reflections on starry nights filled with wonder, until it sometimes feels as if Schulz were exploring the entire universe as it echoed through the cobbled, convoluted streets beyond his front door.

Unlike Kafka, who wrote so obsessively (and hilariously) about individuals lost in a world where everybody knew more about them than they did, Schulz’s child protagonist continually remade the world into something gloriously his own, as in “The Comet,” which begins:

That year the end of the winter stood under the sign of particularly favorable astronomical aspects. The predictions in the calendar flourished in red in the snowy margins of the mornings. The brighter red of Sundays and Holy days cast its reflection on half the week and these weekdays burned coldly, with a freak, rapid flame. Human hearts beat more quickly for a moment, misled and blinded by the redness, which, in fact, announced nothing, being merely a premature alert, a colorful lie of the calendar, painted in bright cinnabar on the jacket of the week. From Twelfth Night onwards, we sat night after night over the white parade ground of the table gleaming with candlesticks and silver, and played endless games of Patience. Every hour, the night beyond the windows became lighter, sugar-coated and shiny, filled with sprouting almonds and sweetmeats…

It’s hard to find a single sentence in this marvelous little book that doesn’t resound with these intimations of magic. And while Schulz knew fame as both an artist and a writer, his brief success preceded one of the most tragic deaths recorded in the history of literature.

During World War Two, after his home town was occupied (first by the Russians, then in 1941 by the Nazis) Schulz was “adopted” by a local Gestapo officer named Felix Landau who, like many educated thugs, enjoyed showing off his appreciation of fine art — by plundering and “Aryanizing” works such as Klimt’s “Lady in Gold,” and later by deploying the renowned (and half-starving) Schulz to paint his portrait, portraits of Gestapo officers’ girlfriends and a mural on the walls of the SS casino. When Landau wasn’t bemoaning the daily tedium of murdering Jews or deporting them to concentration camps, he was penning sentimental letters to his “lovely little Trudchen,” a doting wife who devoutly shared his barbaric enthusiasms. (Landau was often referred to by locals as “the murderer on a white horse.”)

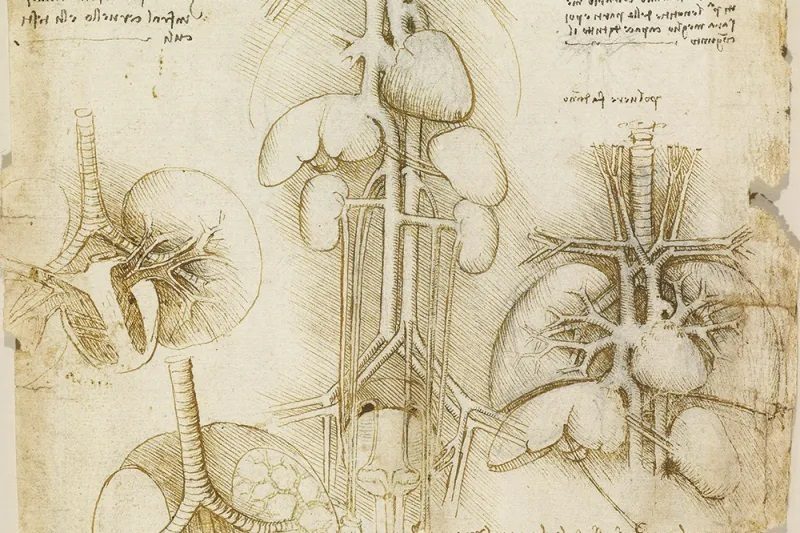

Eventually, he commissioned Schulz’s last surviving work of art, a fairy tale-inspired mural on the wall of the Landau children’s bedroom. Shortly afterwards, Schulz was murdered in the street, carrying home a loaf of bread. By reporting various contradictory accounts of this tragedy, Balint emphasizes the brutal facts common to all of them — that Schulz’s pointless, random killing occurred amid a day of violence against Jewish residents, and several years of casual slaughter.

As a result of Schulz’s death, his life has been burdened by interpretations and re-evaluations that often discount the beauties of his art by focusing on the bloody ironies of his fate; and while he rarely showed much interest in his religious heritage (and even formally registered himself as “without denomination” in order to marry a Catholic), his iconic figure has appeared prominently in the works of Jewish writers, including Cynthia Ozick, Nicole Krauss, Patti Smith and Jonathan Safran Foer.

In 2001, when his last surviving mural was discovered behind shelves of pickling jars in the pantry of an elderly woman in Drohobych, debates over “rightful” ownership ensued, and within months, Israeli agents had secretly removed these fragile images from the wall and transported them to Jerusalem, calling it an act of “repatriation” — even though it was repatriation to a country that didn’t even exist when Schulz was alive. Meanwhile, other parties have claimed him as uniquely their own — such as the Ukrainian government, which now controls the territory where he was born, and Poland, where Schulz is deservedly considered a prominent figure of Polish modernism.

Balint’s biography focuses on the provenance of these rediscovered fragments, and the resulting controversies about who owns an artist after he or she dies. As in his previous book about Kafka’s literary estate, Balint doesn’t take a firm position in these debates, but displays serious (and understandable) impatience with the ways governments and courts often impose themselves between dead artists and what they leave behind.

It’s an absorbing, terrifying history of a special writer who deserves to be known for reasons entirely apart from the historical nightmare that engulfed him.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.