Imagine, if you will, that you are a patron of what used to be euphemistically called “blue movies” at the beginning of 1980, during the so-called “Golden Age of Porn.” The previous few years have seen pornography enter the mainstream in the form of such hugely popular pictures as Deep Throat and Debbie Does Dallas, which saw such stars as Linda Lovelace and Marilyn Chambers briefly achieve nearly the fame (or notoriety) of their Hollywood peers, as their films came close to becoming, if not respectable, at least part of the cinematic fabric of the day. Then you hear tell of something truly remarkable: a big-budget Roman epic with an A-list cast, scripted by Gore Vidal and combining intricately recreated scenes of classical debauchery with envelope-pushing sexual content. Intellectual respectability and onanistic titillation? Where do I sign up?

Those who headed in droves to see Caligula were not put off by the critical ridicule it attracted. Roger Ebert’s dismissal of the picture as “sickening, utterly worthless, shameful trash” seemed almost to be a recommendation; as he noted in his damning review, “I walked out of the film after two hours of its 170-minute length… as a line of hundreds of people stretched down Lincoln Ave., waiting to pay $7.50 apiece to become eyewitnesses to shame.”

And yet, as those hundreds of people settled into the auditorium, it soon became clear that this was not the harmless hardcore romp The Opening of Misty Beethoven had been. Instead, the unholy cornucopia that made its way through the battling visions of Vidal — who took his name off the finished film — its director, Italian erotica auteur Tinto Brass, and its all-powerful producer, Penthouse supremo Bob Guccione, was, to say the least, a challengingly unpleasant watch. Two of its nominal stars, John Gielgud and Peter O’Toole, are barely in the picture, dying after the first twenty minutes or so, and the film’s sexual and pornographic content is nullified as erotica by the sheer unpleasantness of its violence.

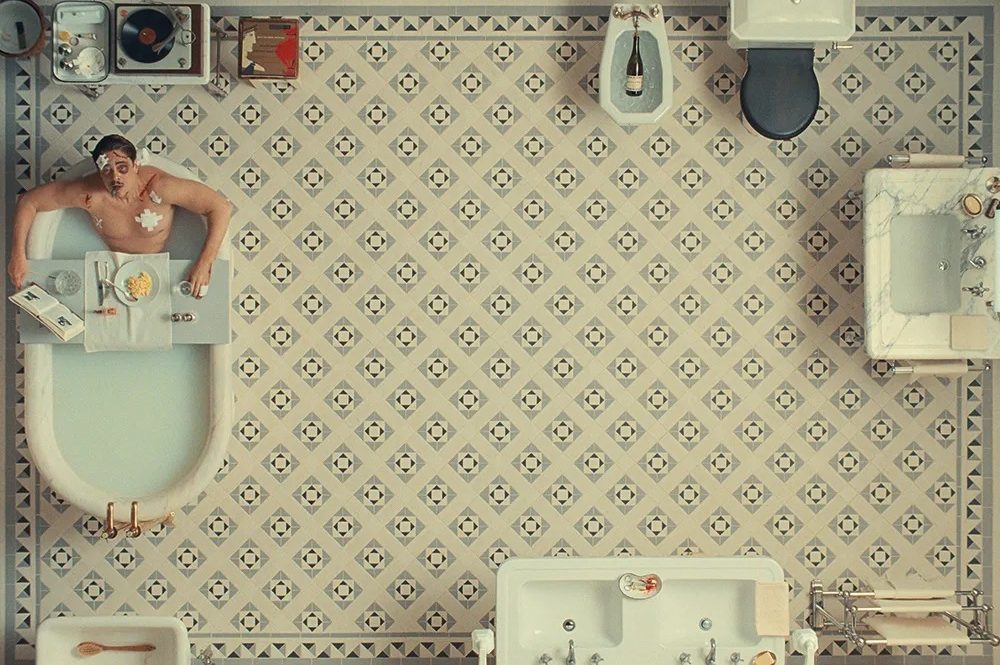

One moment, there may be a relatively tame sex scene involving the film’s Caligula, Malcolm McDowell, and one of his co-stars — Helen Mirren (as his lover Caesonia) or Teresa Ann Savoy (as his sister, Drusilla: it’s that sort of film). The next, there’ll be a jarring, unpleasantly filmed hardcore scene, shot to horrify rather than to titillate.

Or there are scenes of explicit and bloody nastiness that remain hard to watch today, despite or because of their ingenuity. At one point, for instance, Caligula’s enemies are massacred by a threshing machine that operates like a combine harvester, decapitating hapless men buried with only their heads visible, as the deranged emperor shouts, “If only all of Rome had just one neck!”

Caligula has never been regarded as a good film so much as a cautionary cinematic tale. It was conceived by Guccione as an attempt to obtain the artistic respectability he longed for — hence the casting of British Shakespearean actors in the lead roles and the hiring of Vidal — but out of hubris or a failure of nerve, he recut the picture after Brass delivered a final version, and reshot inserts featuring Penthouse stars having sex on screen, none of which had any relevance to events in Rome.

When it was eventually released in Britain and America in heavily edited form, it was regarded as a career-ending disaster for many concerned, especially McDowell, who, after a glorious decade in which he had appeared in such highly regarded classics as If…, its spiritual sequel O Lucky Man! and, of course, Stanley Kubrick’s seminal A Clockwork Orange, found himself demoted to appearing in B-movies for the next few decades, until a welcome reassessment of this fine actor as an elder statesman of cinema followed, along with better roles.

There, under normal circumstances, the whole sorry matter would have rested. But there is something about Caligula that has continued to fascinate everyone from cinematic historians and critics to the prurient alike. For a start, there is no such thing as a definitive version of the film, given that the various cuts that have proliferated since its initial release forty-five years ago are all different. There is the original, X-rated 156-minute version, released in US cinemas to critical opprobrium; an incomprehensible, heavily edited R-rated cut that had to be stripped of all its explicit sex to be releasable on video and which runs around 100 minutes; and now the so-called “Ultimate Cut,” which has been painstakingly reconstructed from the original raw footage by the musician and art historian Thomas Negovan into a new, 172-minute version. It premiered in Cannes last year and has now been released in US cinemas; it will debut on streaming services in due course.

While Guccione, who died in 2010, inevitably had no input into the new version, the now ninety-one-year old Brass has decried it, calling it “a version [in] which I did not take part and which I am convinced will not reflect my artistic vision… If I can’t edit a film, I don’t recognize it, and I have not acknowledged authorship.” Negovan, however, took a rather more scientific approach to the reconstruction, saying “[Penthouse] asked me if I would go and look [the original reels] over, and to tell them if there was anything there that would be worth uncovering. I remember opening one of the boxes and being hit with the smell of vinegar with the film rotting. There was other material in the way of negatives that looked as if they had never been cut and had come straight out of the camera. And at that point I said, ‘This looks significant.’ I had never seen Caligula but I knew the story. I thought it would be criminal to close up these lockers again. That is how it started.”

Negovan’s version of the picture, which has been generally favorably received by critics, is an oddity seldom seen in cinema. On the one hand, it is clearly Caligula — it has the same actors, same storyline and same shocking scenes of sex and violence — but on the other, it is an entirely fresh cinematic experience, with a newly recorded score (by Troy Sterling Nies), different takes and new versions of existing scenes. Large amounts of previously deleted footage have been reinstated.

The most obvious beneficiary of the restructuring is Mirren, whose character is transformed from an insubstantial mistress-type into a scheming and far more interesting protagonist, thanks to considerably more screentime, but the central figure of Caligula is now given a far more compelling arc, too. McDowell is no longer playing someone irredeemable from the outset, but is instead closer to Vidal’s original conception of Caligula as utterly corrupted by unlimited power: a far more interesting role to embody.

No wonder, then, that the actor has praised this new “Ultimate Cut” of the film, saying, “one of my best performances has come to light after forty-seven years” and that “[Caligula] has re-emerged from the total mess of the Guccione porn film into a truly beautiful film… it’s now something I can be proud of.” Mirren, the other surviving star of the debacle, has yet to make a public comment on the new version, but famously described the original as “an irresistible mixture of art and genitals,” indicating that she has long since managed to achieve a degree of amused detachment from the excess and controversy that surrounded its release. This pales in comparison to Gielgud’s take — the greatly respected actor apparently enjoyed the film so much that he paid to see it twice at the cinema, and said to McDowell, when asked if he’d seen Oscar-winner Danilo Donati’s suitably opulent production design, “Oh, it’s wonderful. I’ve never seen so much cock in my life.”

The unkind might suggest that, even in the most artistically respectable version that is ever likely to exist, Caligula remains nothing more than a load of old cock, an overblown and frequently sickening exercise in artistic excess that pales in comparison to the BBC’s far lower-budget I, Claudius. These people may have a point. Yet at a time when we’re going through a mini Roman-renaissance of sorts, with Roland Emmerich’s series Those About To Die released on streaming and Ridley Scott’s feverishly awaited Gladiator II in cinemas next month, it is bracing to have a piece of cinema as out-there and uncompromising as Caligula to debate and discuss.

It’s said that the average man thinks about the Roman empire far more often than seems entirely necessary; this obsession is treated with mystification and dismay by those around them. If this strange, unforgettable film can embed itself in hearts and minds, as it surely must, there will be some very unusual memes going around over the next few years. That, undeniably, has to be worth saying “Hail, Caesar” to.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply