The books that most vividly and expansively illustrate the human experience are not the ones that grapple with life’s most romantic or fantastical tribulations. Charles Baxter’s latest work is splendid proof of this abiding literary fact.

Baxter, a Minnesotan who is author of a multitude of novels and short story collections, returns with Blood Test, a book that delves into some quotidian yet disconcerting aspects of modern American life. He is well-known for 2000’s The Feast of Love, which garnered a National Book Award nomination, and 2020’s The Sun Collective, among others; his new offering continues his tradition of blending the mundane with the extraordinary.

Blood Test opens with deliberate sluggishness, reflecting the pace of life in Kingsboro, Ohio — a small city described by the protagonist, Brock Hobson, as “a cesspool of pollution, addiction, and potential Superfund sites.” This meandering exposition, however, is not a flaw but a clear sign of Baxter’s skill; its slow unfolding mirrors the predictable and structured life of Hobson, an insurance salesman and Sunday School teacher whose routine existence is suddenly disrupted by a shadowy genomics firm.

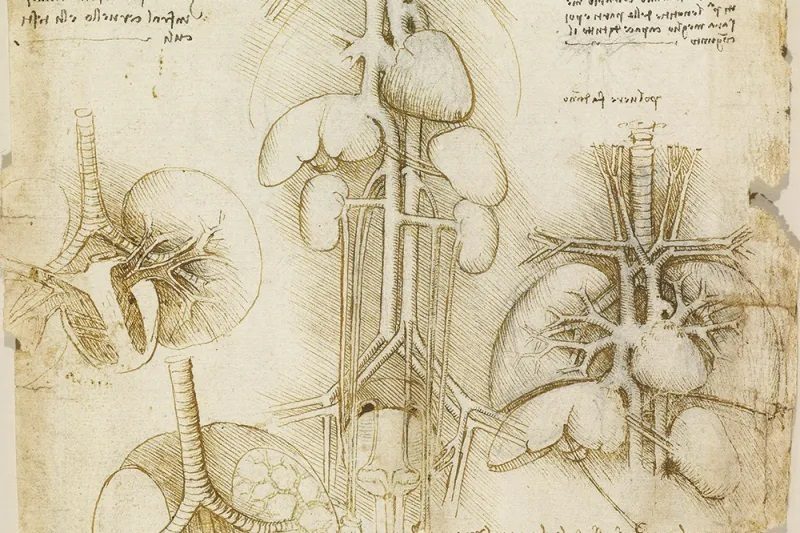

In combining a simple blood test with an assessment of personal attributes and survey responses, the Cambridge-based Generomics is able to predict the future behavior of its clients. That’s what its employees tell Hobson, anyway. As the novel progresses, Hobson grows skeptical of the firm and its proprietary algorithm, obsessing over his decision to become a Generomics customer even as he encounters problems in his personal life that are much more urgent.

Baxter’s prose is a pleasure; he maintains a pensive tone shot through with wit and cleverness: “I’m not philosophical, but even so I don’t understand anything” and “Women don’t like it when you make generalizations about them.” Such moments provide a needed counterbalance to the novel’s more serious themes: depression, suicide, even murder — or, to be more exact, some crude approximation of murder.

The moral implications of something as seismic as homicide are explored throughout Blood Test: Baxter shows temptation pulling firmly in one direction, while faith, fear and the sort of obstinate friendliness that seems innate to Midwesterners pull in another.

The novel overflows with painfully recognizable characters. Indeed, Blood Test’s vignettes are instantly familiar to anyone who has walked down a street in the post-pandemic years. While sitting on a public bench, for instance, Hobson meets a vagrant who introduces himself as Dr. George B. Graham the Third, a man who quickly descends into a psychotic (though admittedly diverting) tirade about the British royal family, Henry Kissinger and secret Antarctic mining operations. If you are an American with the nerve and moxie to venture out in public in this opioid era, encountering Dr. Graham will feel like replaying 4K GoPro footage in an Oculus headset.

To say that Blood Test has a strongly masculine perspective is tempting, but not quite fair. Hobson’s ex-wife, girlfriend and daughter are thoroughly developed, complex, and mostly likable characters, with interesting thoughts and impulses and outpourings of emotion. But it’s true that the novel’s overridingly male ethos feels unusual — even valuable — in an age of literary fiction that largely projects female experiences and overwhelmingly caters to female preoccupations. Joe Hobson, Brock’s fifteen-year-old son, embodies the confusion and nihilism of contemporary youth — especially of teenage boyhood — tortured by evolving conceptions of masculinity. The depiction of Joe is refreshingly fair and convincing, free from the awkward anachronisms that often plague works by older authors like the seventy-seven-year-old Baxter. Instead, Blood Test is imbued with up-to-the-minute references, from Childish Gambino tracks to TikTok trends, which convey an acute awareness of America’s current cultural texture.

Throughout Blood Test, Brock Hobson navigates the challenges of fatherhood, courtship and the oppressive forces of late-stage capitalism. Baxter’s exploration of these themes is nuanced, capturing the existential dread that permeates life for many in 2024, just as Hobson’s paranoia about the genomics firm mirrors broader social mistrust of technological determinism and corporate overreach.

The novel’s central conceit — a blood test that claims seemingly impossible predictive power — serves as a sharp satire of our data-driven, algorithmic age. Baxter critiques the invasive nature of technology through the intrusive investigations of the genomics company’s actuaries. This portrayal of a world where every intimate detail becomes a data point (and therefore a salable asset) is unsettling and thought-provoking, echoing contemporary concerns about privacy and data commodification.

In Blood Test Baxter has crafted a testament to his enduring literary talent as well as a remarkably relevant work that speaks to the lives led by normal people these days, a book that blends humor with profound social commentary, offering a severe yet thoroughly entertaining exploration of contemporary American life. It is a necessary novel for right now.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply