In March 2014 Gabriel García Márquez went down with a cold. The man who wrote beautifully about aging was approaching his end. As his wife told their son Rodrigo: ‘I don’t think we’ll get out of this one.’

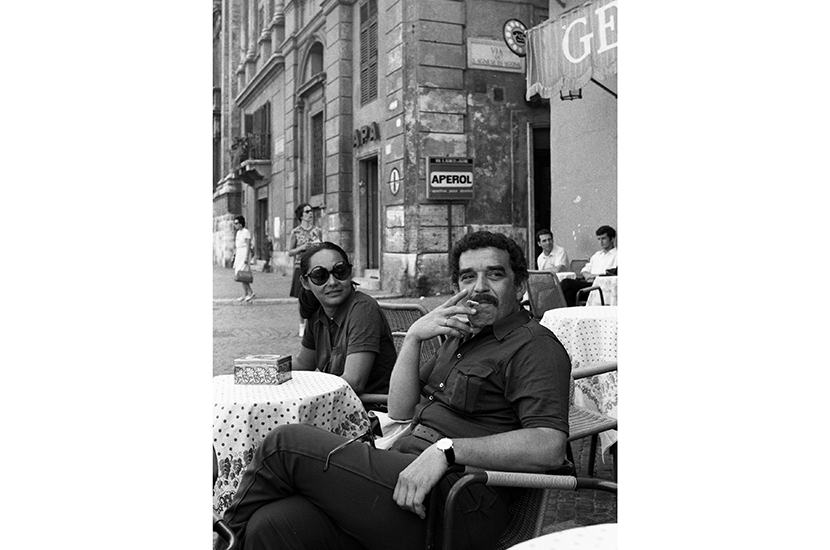

In A Farewell to Gabo and Mercedes, García, a film director and screenwriter, remembers his father and mother — one of the world’s greatest novelists and his muse. Comprised of short chapters, some of which reflect the journal he wrote while traveling back and forth between his LA cutting room and the family home in Mexico City, the book turns the venerable writer into a lively protagonist. The García Márquez who emerges is a quintessentially García Márquezian character.

His final days arouse particular interest because of the prevalence of aging and death in his novels. The Autumn of the Patriarch focuses on a debilitated but tenacious dictator; The General in his Labyrinth describes the final journey of the ailing Simón Bolívar; and Love in the Time of Cholera concludes with the gerontic love affair of Florentino Ariza and Fermina Daza.

In his dotage, García Márquez has the spry humor characteristic of his novels. When he wakes to find himself surrounded by half a dozen women — housekeepers, nurses and secretaries — he says, without missing a beat: ‘I can’t fuck all of you.’

He wasn’t always so sharp. For months, the elderly Nobel laureate had suffered from such severe dementia that he thought an impostor was standing in for his wife. And when his housekeeper informed him that the two people he’d just seen were his sons, he was amazed:‘Really? Those men? Carajo. That’s incredible.’

It’s hard not to contrast his dementia with his fiction, which is premised on memory. ‘Memory is my tool and my raw material,’ he once said. ‘I cannot work without it.’ Both Love in the Time of Cholera and One Hundred Years of Solitude begin with memories: the scent of bitter almonds which reminds Dr Urbino of unrequited love, and the colonel’s recollection of that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice. One Hundred Years of Solitude even features an amnesia epidemic.

In the writer’s final hours there is an extraordinary moment of life imitating art when a bird is found dead in the house. The logical explanation, says his son, is that ‘the bird flew in, became disoriented, crashed against the glass and fell dead on the sofa’. Astonishingly, the episode mirrors the scene from One Hundred Years of Solitude when, after the death of the matriarch Úrsula, birds fly into walls and fall dead on the floor. What’s more, like Úrsula, her creator died on Maundy Thursday.

García’s memoir then turns seamlessly to his mother — a titanic, e-cigarette-smoking, matter-of-fact woman who passes on the news of her husband’s death to a friend ‘as if she were talking about a food delivery’. She silently watches the obituaries on television, engrossed. After the funeral, during which the Mexican president referred to her as ‘the widow’, she threatens to tell the first reporter she meets that she intends to remarry post-haste. ‘I am not the widow,’ she huffs. ‘I am me.’

The third protagonist of the memoir is the somewhat reluctant author: ‘I am appalled that I am thinking of taking notes, ashamed as I take notes, disappointed in myself as I revise notes.’ If he is writing for consolation, that task is made harder by what he calls ‘God’s sense of humor’. During his father’s final month, García is editing a film about the death of a father.

The son’s prose can only suffer from comparison with the master, but overall this is a powerfully written, if not always beautiful, memoir. Even when the material is undercooked — such as the chapter in which he comments on his father’s relationship with success, which seems to end mid-thought — it retains the raw energy of a son dealing with grief. It also helps fill in the canvas of his father’s life. By providing an intimate portrait of the writer as an old man, it complements Living to Tell the Tale (2002), García Márquez’s memoir of his adolescence and early writing career, and Gerald Martin’s definitive 2009 biography.

García Márquez maintained that his novels were inspired not by magic but by reality. His son’s memoir shows that, when it comes to his father’s life, it is impossible to separate the two.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.