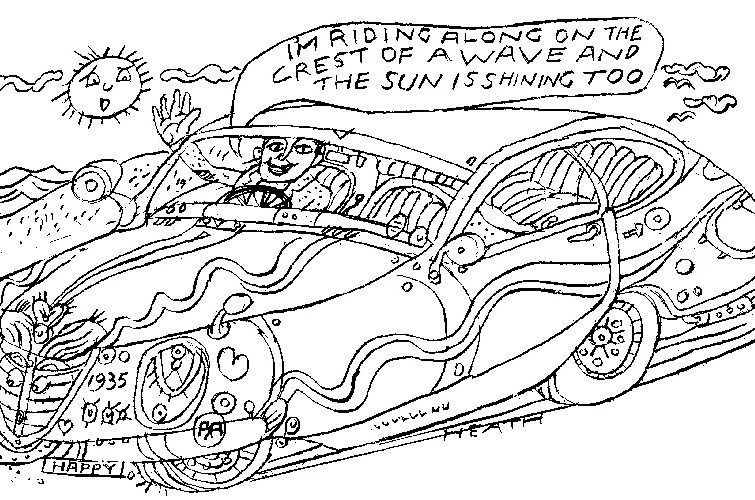

One of the more unusual works in the family art collection is a concept drawing of an automobile from 1937. The car, identified by the angular writing on its nose, is the LaSalle.

To call this a drawing of just a car does a disservice to the concept behind it. With its shimmering grilles and Futurist forms, the vehicle might as well be an open-cockpit fighter plane about to strafe a runway. Automobile enthusiasts, as I recently learned, consider the drawing to present one of the first known examples of a ‘ripple-disk single-bar flipper hubcap’. Clearly, here is a machine meant to do more than just deliver you from point A to point B. It is a vehicle for transporting desire, for mowing down all obstacles in your path, for getting you wherever you want to go with whatever means it takes.

My grandfather, James Ross Shipley, created this concept drawing when he was a young art-school graduate working in Harley Earl’s Art and Color Section at General Motors. The fanciful sketch reveals much about the creative origins of car design. The man behind it — behind the way we even think about ‘the car’ — was Earl, my grandfather’s boss and the industrial designer who made Detroit.

The bones of the automobile have changed little in over a century. Even the electric-car revolution, so far, has not altered the basic construction of an engine on a frame with four wheels. And before Earl, a car was little more than just that. You bought your vehicle unfinished and sent it to a coachbuilder for body fabrication. Earl began his career customizing the early cars of Hollywood in this way, but he also gave them something more than just a hood, a trunk, a windshield and some seats. When he arrived in Detroit, his genius was to turn the car body into an object of love, to convey more than mere conveyance, to make it all something on an industrial scale that we would want to acquire, occupy and control. He also expected us to trade it in when the new ‘model year’ came out — built-in obsolescence being another one of his great innovations.

Detroit Style: Car Design in the Motor City, 1950-2020, a new exhibition organized by the Detroit Institute of Arts, reveals the driving influence of American car design over the post-war period. As a constellation of car companies consolidated into the Big Three — GM, Ford and Chrysler — their design teams competed to capture the evolving American spirit in mobile form.

The exhibition tells this tale through ten vehicles, displayed along with the story of their designs, side-by-side with concept drawings and related automobile-inspired art. The exhibition begins with GM’s 1951 Le Sabre, a convertible of tapered nose and heavy chrome that resembles a fighter plane. With its wing-like hoodline and jetlike intake and exhaust grilles, the Le Sabre speaks to the power look of Earl’s GM. Glittering ornamentation is built right into its curving forms. Earl wrote in a 1955 brochure that he intended to make ‘these useful things beautiful, not in the sense of applying superficial ornamentation, but in developing a form of beauty exactly suited to the purpose’. ‘People like something new and exciting in an automobile as well as in a Broadway show,’ he added. ‘They like visual entertainment, and that’s what we stylists give them.’

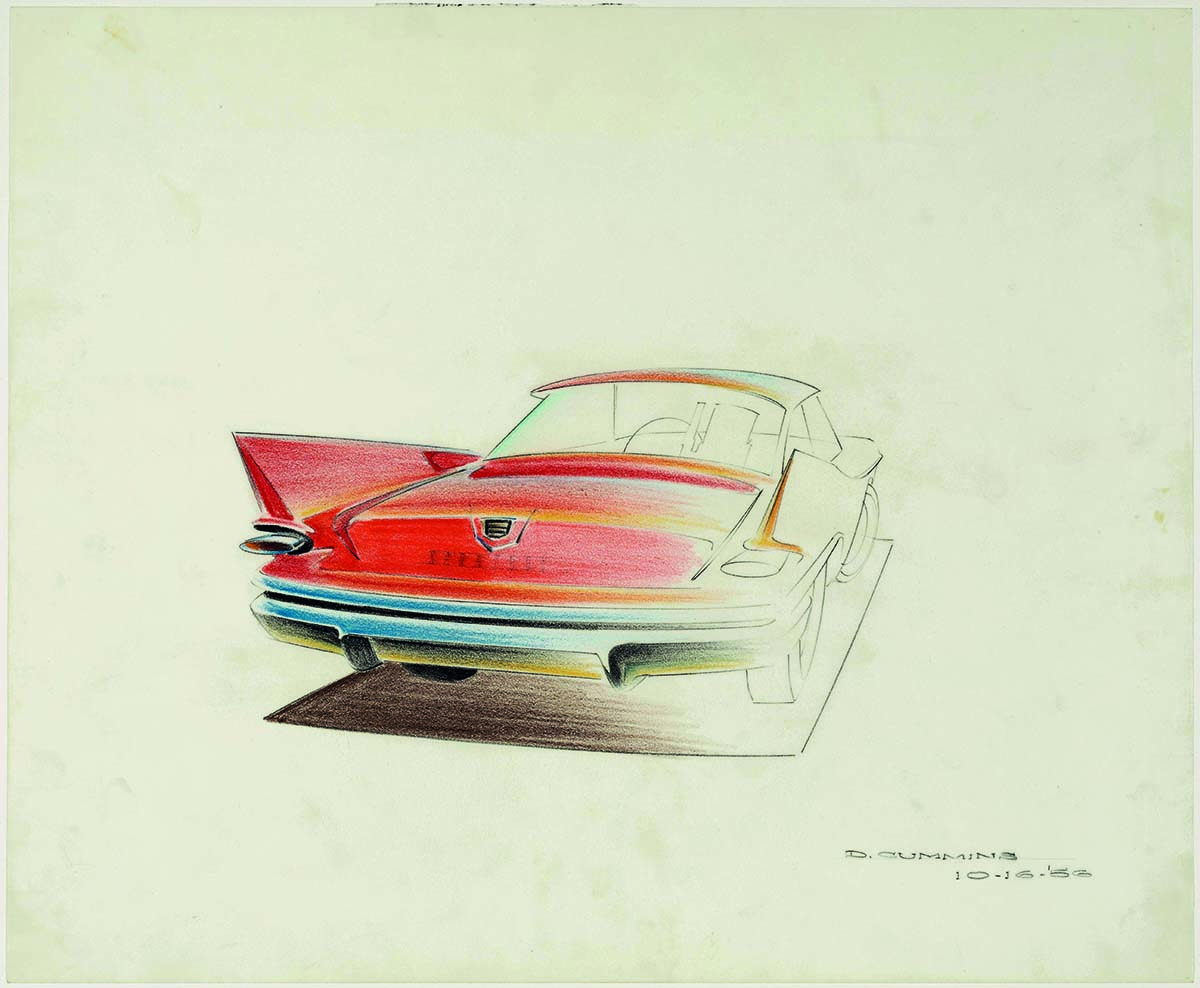

There is power in Le Sabre’s bulging forms and cut lines, but the overall massing is also heavyweight and over-the-top — all muscle, no brains. Compare this to the next model on display: Chrysler’s 300C of 1957. Rather than roaring through the air, here is a car that looks like it could float on water. In the 300C, Chrysler’s design team, led by Virgil Exner, championed a ‘Forward Look’. With reduced chrome and a single grille, the car’s bulk is now ‘concentrated toward the rear, crowned by the upsweep of the tail,’ Exner explained. ‘Big racing boats take the same general form.’ The Chrysler’s tail is not a wing so much as a line of wake. You could imagine this elegant vehicle motoring through the canals of Venice, with headlamps like lashy eyes beckoning you on.

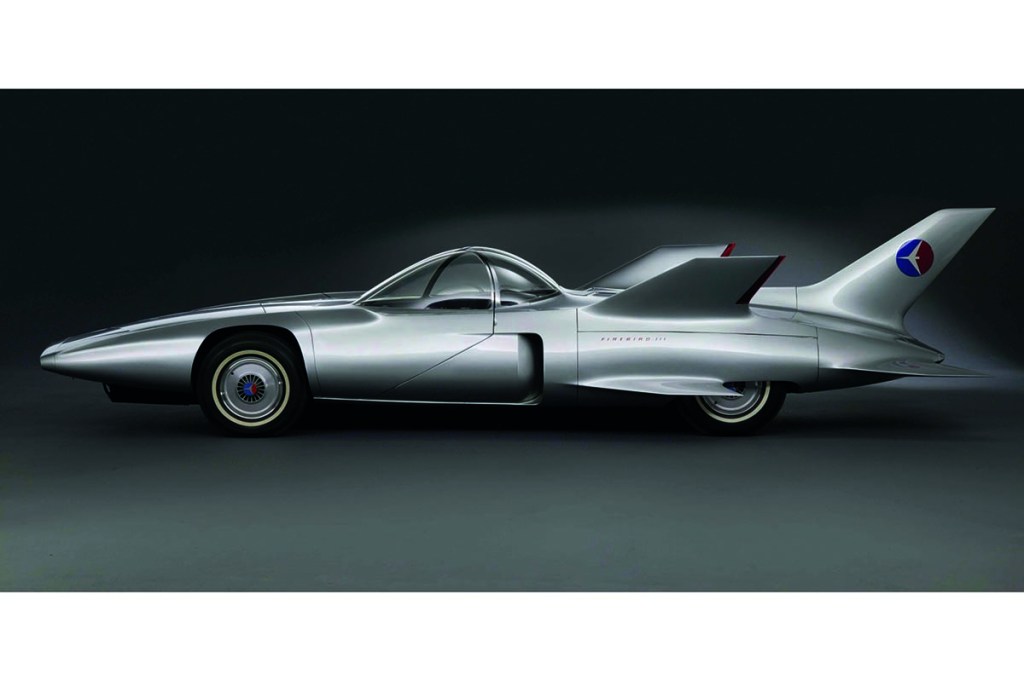

As the jet age became the space age, Earl set his sights higher. For his Firebird III concept car, he wanted ‘what you would expect the astronauts to drive to the launch pad on their way to the moon’. The result was the apotheosis of fin, as much Batmobile as automobile. This Firebird’s abstracted forms continued to influence 1960s car design even after its wings were clipped.

The Sixties proved there was more to car design than flying forms. Some cars took on natural shapes. The 1959 Corvette Stingray Racer, a stunningly attractive concept car from GM’s new head of design Bill Mitchell, conveys the teardrop shape of a sea creature. Meanwhile the 1967 Mustang, Ford’s wildly successful ‘pony car’, references the smoothness of a saddle mounted atop a galloping heart (made all the more apparent in the iconic equine grillework).

In the 1970s, Detroit doubled down on power. The 1970 Chrysler Plymouth Barracuda borrowed lessons from such cars as the 1966 GM Oldsmobile Toronado to represent strength in brutalist, hard-edged form. A straight beltline ties the body together from headlight to tail. A flat front end presents a menacing blackened maw with a hood scoop of simian nostrils.

A decade later, after an oil embargo or two, Detroit was ready to repent. With its chastened forms, the 1983 Ford Probe IV puts the car in an exercise leotard. Aerobics and aerodynamics now came to represent Detroit’s supposed new efficiency. Computers and wind tunnels, as much as the clay model, came to define car design. The 1987 Chrysler Portofino, a concept car designed by Sergio Coggiola at his Carrozzeria Coggiola near Turin, also shows the growing influence of European styling over Detroit. Here torsional forms replace lines of lateral speed. In a surprising Futurist move, the doors, hood, and trunk all rotate up to reveal an entirely open cabin.

By the 1990s, Detroit looked to the past as much as the future. Nostalgic designs appealed to the same car buyers who coveted the Detroit designs of decades before. As its name suggests, the 1998 Chrysler Chronos is a time machine back to the 300C and Exner’s Forward Look. In the Ford GT Concept of 2002 and the 2017 Ford GT, the final two cars of the exhibition, the end results are back to the future. The forward styling of the past now informs designs that are still to come.

I never got to ask my grandfather about his car-designing days. As he went on to become a professor of industrial design, all I heard of his time in Earl’s shop was that it was long hours for little pay. ‘Automobiles are hollow, rolling sculpture,’ said Arthur Drexler, MoMA’s curator of architecture, at mid-century. The automobile’s artifice is its art, but it is still an art of artifice — one designed, in the end, merely to sell you a new car.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2020 US edition.