Are the Rolling Stones the new Rat Pack?

Or put it another way: how did the Stones achieve this curious headlock on our affections? If anything, it seems to get stronger over time. In the band’s current US stadium tour, aptly sponsored by the old-age interest group AARP, a million customers are each paying $100 for a seat that allows you to aim a pair of binoculars at a distant video screen. Want an actual view of the stage? It’ll cost you up to ten times as much. Still, it’s all gravy. The last major Stones tour grossed $550 million at the box office. Add a couple of hundred million for all those souvenir T-shirts and Mick Jagger bobbleheads, and you’ve got roughly the same total as the annual operating budget for Pittsburgh, with enough left over to buy out the eight-seat Virgin Galactic for a morning’s space tourism.

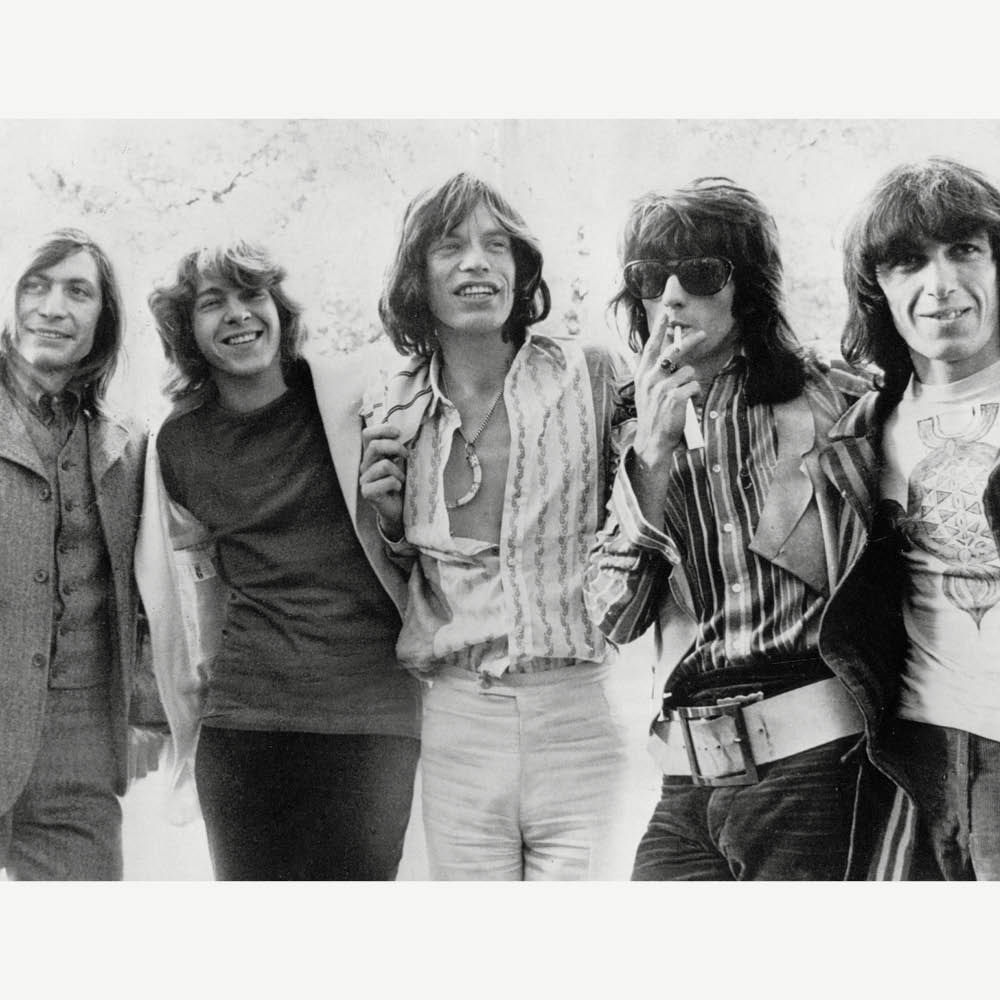

But to get back to the Stones and the Rat Pack. Am I alone in noticing the resemblance? Watching the three surviving band members go through their paces today brings memories of another trio of well-seasoned performers lurching around stage with a tumbler of Jack Daniels in hand, even if the cigarettes the Stones’ twin guitarists once smoked as relentlessly as laboratory beagles now seem to have gone the way of the more exotic stimulants.

The notion that Frank Sinatra’s touch of macho swagger and Dean Martin’s engaging slur might have been handed down to, respectively, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards seems only fitting, while Sammy Davis Jr. visibly lives on in the hammy, spindly-legged Ronnie Wood. It’s Robin and the 7 Hoods all over again, part drama, part shtick, above all offering a sort of vicarious buzz in seeing old codgers behaving badly.

Because they’re so brazen, so unapologetic and so astonishingly upfront about it, the Rolling Stones have gradually acquired special status as the officially tolerated moral slobs of the middle class. On some fundamental level, we need the Stones, if only as a living reminder that one of rock music’s chief initial functions was to act as an emotional pick-me-up for a weary public. What a sad lot most of today’s stars are by comparison.

As it happens, there’s another link between the Stones and the Rat Pack’s take on the Robin Hood myth, because both were unleashed on the American public exactly sixty years ago.

The Stones’ first contact with the US, in New York on June 1, 1964, came as something of a mutual shock. There was at least a modest welcome awaiting them at the newly-christened John F. Kennedy Airport, where the band’s management had bused in a couple of hundred local teenagers to greet them. Also on the upside, it was to be the sort of accessory-heavy tour that continues today, with a line of “exclusive merchandise” including everything from socks to underwear to newsboy caps. If a teenager could wear it, Mick and the boys were on it.

On the downside, there were the indignities of the band’s reception by the mainstream media. The Stones’ first major TV appearance came on the old Hollywood Palace show, hosted by Dean Martin himself — in retrospect, a logical baton-handing development, if less obviously so at the time. Martin and the Stones loathed one another on sight. The generational clash started the moment the band arrived and continued through their brisk performance of “I Just Wanna Make Love to You,” during which Brian Jones appeared to repeatedly flip off his host while playing the harmonica. Lurching towards the old-fashioned stand mike, Dino then delivered a monologue about the Stones having “low foreheads and high eyebrows” before introducing a trampolinist as “the father of the band — he’s been trying to kill himself ever since.”

On June 5, the Stones played their first live American concert at the 10,000-seat Swing Auditorium in San Bernardino. Thanks in part to name-checking the town in the opening number, “Route 66,” the band went down a storm. Such was the commotion that nobody on stage noticed when a teenaged boy flipped out, wrestled a policeman’s gun away from him and sent a bullet into the plywood floor just feet from where Mick Jagger was dancing around with his maracas. That aside it was a promising start, if not entirely representative of the Stones’s reception as a whole. After San Bernardino, the group played four generally less well-received shows in Texas, where they appeared before a backdrop of hay bales and horse manure at the San Antonio state fair. The band’s local warm-up act was a tank of trained seals, and immediately afterward a performing monkey, who, unlike them, was called back for an encore.

There was another upswing of the band’s fortunes back in New York, where they played two riotous shows at Carnegie Hall. Even before the band slouched onstage, the screaming reached the pitch of a jet aircraft. The night’s emcee, the local disc jockey Murray “the K” Kaufman, kept his introduc- tion short. “Lezz ’n’ gennelmun, the Rolling Stones. Let’s hit it!” It wouldn’t have mattered had he been reciting the Black Panther Party manifesto, because the words were lost in a cyclotron of hormonal abandon. Amid ear-splitting screams throughout, the Stones blasted out an eleven-song set, threw down their instruments and ran. That concluded the band’s freshman tour of North America. The five musicians weren’t entirely satisfied by the experience, and

Mick Jagger was particularly disenchanted by the advance arrangements in Detroit, where they performed in front of 371 customers dotted around the 14,000-seat Olympia Stadium. “We feel we’ve been given the business here,” he noted at a sullen eve-of-departure press conference. “We’ll never get involved in this kind of crap again.”

And to be fair, they haven’t. The numerous Stones tours since then have been an exercise in steadily accumulating comforts (like the backstage vases of precisely arranged, dethorned white roses stipulated in their current contract rider), as well as proof positive that Jagger and company were the first to realize that the business of jetting around the world banging out your old hits would become divorced from actually making records: you no longer need to do the latter to make millions doing the former. These things are necessarily subjective, but there are apparently sane Stones fans out there prepared both to pay the equivalent of a month’s rent to see the band in concert and to unblushingly tell you that the last really good album they made was 1972’s Exile on Main Street.

All of which raises the question of how, exactly, the Stones have kept the show on the road when almost all their contemporaries, Paul McCartney excepted, have long since given up the struggle, or at least settled on a life of cringe-inducing appearances flaunting their beer-guts and dodgy hairlines on the nostalgia circuit.

For one thing, it probably doesn’t hurt that for much of the past sixty years Mick Jagger and Keith Richards have had access to the very finest medical and (especially in Keith’s case) legal back-up money can buy. When in 2019 Jagger needed a heart-valve operation he was immediately flown by private jet to a New York hospital and was later able to recuperate first at his beachfront home in Florida and then at his château in the Loire Valley, which was also where he rode out the Covid pandemic. And good luck to him; he’s earned it. But it’s not exactly the six-month wait for a similar procedure on Britain’s National Health Service, followed by a convalescence, or lockdown, in one’s suburban abode.

Similarly, when in 2006 Richards fell while relaxing in the branches of a palm tree in Fiji and hit his head on landing, a full-scale emergency team swung into action. An air ambulance flew the veteran guitarist to the nearest major hospital, in New Zealand, where surgeons drained blood from the patient’s brain, reattached his scalp and put him on a morphine drip, thought to be a not wholly unfamiliar experience for him. Remarkably, Keith was back on the road with the Stones just weeks later.

But perhaps the secret to Jagger and Richards’s longevity goes further back than that — and has its roots in the values with which they grew up in the bracingly austere years of postwar Britain.

In Jagger’s case, this involved a childhood in suburban London characterized by hard work, service to others, a carefully rationed diet and a grueling exercise regime supervised by his physical education-buff father Joe. For at least the first twenty years of his life, Mick’s routine took place amid a welter of sporting equipment and barbells — and was punctuated by twice-weekly attendance at the local Anglican church, where he was known not so much for his singing voice as for his volunteer work and a quiet determination to make something of himself.

In 1962, Jagger’s school-leaving report called him “a lad of good general caliber” with “a quality of persistence when he makes up his mind to tackle something.” More than sixty years later, it would be hard to quibble with that core assessment of his character.

Similarly, some discrepancy exists between the raised-by-wolves legend of Keith Richards’s upbringing and the reality, with its emphasis on duty, rank and sound traditional values. Richards’s paternal grandparents were both well-respected town councilors in the London borough of Walthamstow, where his grandmother served as the first female mayor. His pater- nal grandfather was a decorated World War One hero. Richards’s father was among the first troops to hit the Normandy beaches on D-Day and was badly wounded as a result.

Perhaps there was a touch less emphasis on physical fitness than across town at the Jaggers’, but Keith still grew up with the benefits of a largely fat-free diet, as well as a fundamental sense of patriotism and service. As a nine-year-old, he was remembered as an “angelic-looking” chorister (yes, this is Keith Richards we’re speaking about) performing for the newly crowned Queen, earned his merit badges as a Boy Scout, and later showed a pronounced streak of English romanticism by spending his first songwriting money on the thatched cottage in the Sussex countryside where he still lives today.

As Richards himself once put it, in his inimitable style: “I can be the cat on stage any time I want. But really I’m a very placid, nice guy — most people will tell you that. It’s really just to placate this other character that I work.” A prince of darkness, perhaps, but a prince nonetheless.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply