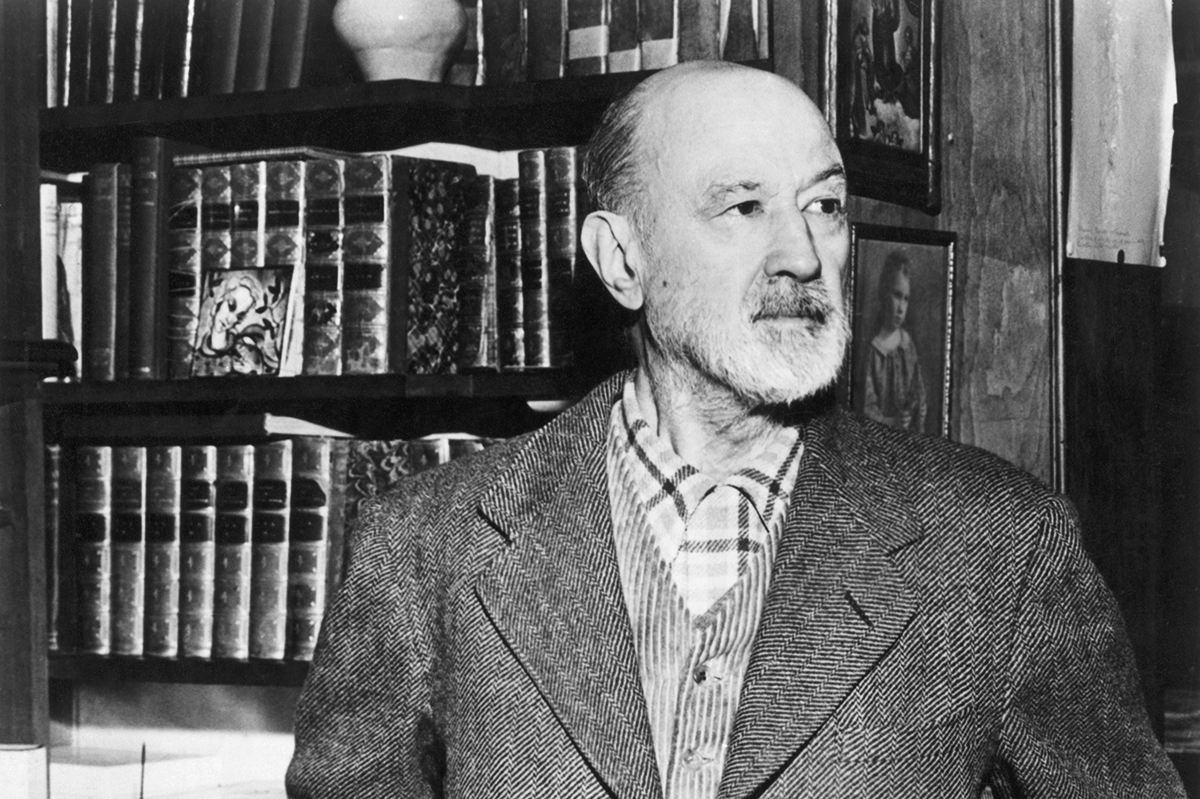

Imagine a John Le Carré thriller — one of the Cold War ones, not the tedious lefty morality tales — in which we meet Moisey Vainberg, a Polish Jewish composer who defected to Russia in 1943 while the rest of his family was wiped out in the Holocaust. He dresses like a mid-level bureaucrat and seems nervous about drawing attention to himself. That’s sensible, given that under Stalin he was thrown into jail for ‘Jewish bourgeois nationalism’.

Then he’s rehabilitated, his music enjoys a brief vogue, he’s performed by Rostropovich, Shafran, Gilels, Kogan and the Borodins — but he never boasts or promotes himself. A few recordings reach the West, but the critics wrinkle their noses. They think his stuff is well crafted, the mandatory Soviet bleakness flavored by Jewish idioms — but hasn’t a much greater Russian composer made that his hallmark, despite not being Jewish? And so Vainberg earns the deadly reputation of being a dime-store Shostakovich.

He takes it on the chin and straightens his tie. (I can see the late Bernard Hepton doing this to perfection in the BBC adaptation of my imaginary Le Carré drama.) He carries on writing his 22 symphonies, 17 string quartets, operas, film music, innumerable concertos, chamber works and solo sonatas. He knows he’ll never hear most of them, that to the ordinary Russian he’s just the guy who wrote the music to the Vinni-Pukh cartoons, the Soviet version of Winnie the Pooh. And that’s fine, because if children are gurgling to Vinni-Pukh then it’s less likely that he’ll have his head shaved and face nighttime interrogation in subzero temperatures. Once was enough. He doesn’t even complain when, in the mid-1970s, his friend Mstislav Rostropovich — the first champion of the Vainberg Cello Concerto — moves to America and stops playing Vainberg because he thinks he’s ‘a coward’ for staying put.

The Soviet Union collapses while Vainberg is in bed with Crohn’s disease, a hideous illness that doesn’t stop the manuscripts piling up. Now music critics in the West finally have access to a fair cross section of his work and they’re having a rethink, but it’s too late. He dies on February 26, 1996.

Then there’s a plot twist, one of the strangest in the history of classical music. Moisey Vainberg is resurrected as ‘the third great Soviet composer’ after Prokofiev and Shostakovich. In the process, his name changes. Moisey becomes Mieczysław — and quite rightly: he was told to call himself Moisey by a Soviet border guard who thought Jews arriving from Poland ought to have Jewish names. Vainberg is rendered as the more conventional Weinberg in the new Grove Dictionary of Music, which had previously declined to notice his existence.

Critical superlatives rain down on the composer’s freshly dug grave, though few people notice the surprising words on his gravestone, of which more later. The violinist Gidon Kremer and his Kremerata Baltica throw themselves into Weinberg’s solo, chamber and orchestral music with magnificent passion. The critic and scholar David Fanning publishes a groundbreaking study that points his colleagues towards musical buried treasure. Stephen Walsh, one of the big guns of Russian musical criticism, writes about ‘The Genius of Mieczysław Weinberg’. He hears Weinberg’s 1968 opera The Passenger and is astonished by ‘the brilliance and beauty of his writing for the voice. This is real singers’ music, music that soars, that floats, that talks, that serves the words in countless trivial and crucial ways.’ He also finds the Sixth Symphony ‘invariably striking, confident, highly personable, strongly fingerprinted… in every way a marvelous symphony’. And the ‘shimmering third movement’ of Weinberg’s Third String Quartet is ‘as beautiful a piece of quartet-writing as anything in Shostakovich’.

Walsh was writing in 2010. Since then, the Quatuor Danel has finished recording its Weinberg cycle, delicate and precise like its Shostakovich quartets; the more red-blooded Silesian Quartet is 12 quartets into its own cycle and the Arcanto Quartet has recently begin a third. In 1996, when Mark Morris published his Guide to 20th Century Composers, an incomparable survey of thousands of pieces of music, all he was able to say about Weinberg’s Piano Quintet was that it was ‘reportedly a fine work’: the composer’s blistering performance with the Borodin Quartet had disappeared from the catalog. Now you can choose between a dozen versions, including the original.

The best-selling Weinberg disc, however, is Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla and the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra’s 2019 recording of his slender second Symphony and epic 21st Symphony. The 21st was the last the composer completed. It’s subtitled Kaddish, after the Jewish prayer for the dead, and is dedicated to the victims of the Warsaw ghetto. In it we hear the bittersweet jauntiness of klezmer tinged with apocalyptic horror. The critical consensus was that here was a symphony worthy of its subject, the suffering of Jews in the 20th century. Alex Ross of the New Yorker declared it ‘fully the equal of the later symphonies of [Weinberg’s] longtime friend and mentor Shostakovich’. Gramophone magazine voted it Recording of the Year.

At this point I still hadn’t heard any Weinberg and was dragging my feet. We’d just had to endure an anniversary year of ridiculous claims for the music of Clara Schumann; now there was all this hype about a long symphony by a Shostakovich-lite featuring a wordless soprano. (Wordless singing is fine as a camp accompaniment to a B-movie, but in serious music it makes me sweat with embarrassment.) Also, the depiction of suffering is no guarantee of musical authenticity. I’m still haunted by Górecki’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, and not for the right reason.

Then a friend told me I really must hear Weinberg’s Piano Quintet. In less than a minute I knew that here was a composer touched by genius. Against a nervous rustling of strings, the piano picks out a unison melody shaped like no other: it’s enchantingly lopsided and immediately stolen by the strings, which slather it in neurotic harmonies. Then it’s reclaimed by the piano, whose simple octaves say: ‘Hey, this one’s mine!’ The strings launch into a fiercely dotted second subject around which the original tune quickly wraps itself. The themes flit between the piano and the strings, alternately fighting and melting into each other. And Weinberg sustains this startling level of inspiration throughout the work.

The finale begins with the strings sawing away while the piano throws down a catchy nine-note motif; they switch places, the piano hammering out repeated chords as the strings pelt us with the motif at ever-shorter intervals. Just as the Soviet savagery threatens to become unbearable, we’re bundled into an Irish jig, of all things, and the lopsided tune from the first movement joins in. Juxtaposing these ideas is a massive risk compositionally, but Weinberg’s gamble pays off. The whole thing is astonishing — not just the music, but the fact that one of the greatest piano quintets ever written was shoved into a drawer and forgotten about for decades.

So now I had no excuse to ignore the rest of Weinberg’s output. But where to start? I opened Spotify, which is full of new recordings of his work: there’s a musical gold rush going on. I clicked at random on the String Quartet No. 11. As in the quintet, the spikiness of Shostakovich and Bartok is softened by catchy motifs: Weinberg was a master of the earworm. Also, his ability to compress his inspiration, using contrapuntal tricks to say a lot in a short time, reminded me of Haydn. The 12th Quartet — there are no keys in the titles — was even more of a revelation: listen to the third movement, marked Presto, in which rising arpeggios slash across the page, creating an unhinged rocking movement that reminds me of nothing I’ve heard before. Yet some of the sparse harmonies do sound very much like Shostakovich.

But so what? Mozart sometimes reminds us of Haydn and vice versa.The two composers were friends and influenced each other, despite the 24-year age gap between them. One thing is becoming increasingly clear: Shostakovich drew on the work of his protégé, 13 years younger, not just in his use of Yiddish musical tradition but also as a source of ideas. As the Weinberg scholar Daniel Elphick points out, Weinberg began composing quartets before Shostakovich did. His Second Quartet of 1939 contains ‘tantalizingly close resembles to Shostakovich’s later works’, written decades later.

It’s true that Weinberg’s music is full of moments that could be mistaken for Shostakovich, and perhaps there are too many of them, but they’re only moments. Elphick writes that Weinberg ‘presents a central narrative of struggle, evasion, and self-reflection, while Shostakovich gives a narrative of confrontation and self-destruction’. To put it crudely, he doesn’t make you want to slit your wrists, as I long to do every time I hear Shostakovich’s last string quartet, No. 15, a series of six adagios — a breathtaking masterpiece but, as the conductor Kurt Sanderling put it, so ‘unfathomably terrifying’ that the composer didn’t want to traumatize anyone by dedicating it to them.

Alongside Weinberg’s compulsive desire to startle — for example, by beginning his glorious Seventh Symphony with a harpsichord solo, or by having the soloist in his Trumpet Concerto suddenly lapse into Mendelssohn’s Wedding March — is an equally compulsive quest for spiritual peace. You can find it (if you can stomach the wordless singing, which I can’t) in the conclusion of the Kaddish symphony, which after confronting horrors achieves a very un-Shostakovichian tranquility. And this from a composer who was tormented daily by imagining the deaths of his family, and especially his sister, in the Nazi genocide.

Weinberg was grateful to the Soviet Union for saving him from the Holocaust and seems to have believed that it could do no wrong. He brushed off the fact that it nearly murdered him for being Jewish; he was happy to write an opera, The Madonna and the Soldier, which, as David Fanning notes, is based on ‘the supposedly comradely fellowship between wartime Polish villagers and their heroic Red Army liberators’. Likewise, his Ninth Symphony celebrates Russia’s role in ‘liberating’ Poland. ‘He may well have been unaware of the atrocities committed by the Red Army in that process,’ writes Fanning, ‘and he would probably have been disinclined to believe it, had he been told.’

This supine attitude is presumably what Rostropovich had in mind when he was asked by the cellist Josef Feigelson why he’d never performed the 24 Preludes for Solo Cello that Weinberg wrote for him and replied: ‘He was a coward.’ Was that fair? Weinberg may have been indefensibly naive and overeager to please, but at least he never joined the Communist party in order to boost his career. Shostakovich did, and Rostropovich didn’t stop performing him after he defected. Perhaps the difference was that Western audiences wanted to hear Shostakovich but knew nothing of Weinberg, and the self-obsessed ‘Slava’ didn’t want to take the risk. It’s interesting to speculate that he could have changed the course of musical history if he’d built those 24 preludes into his repertoire at the height of his fame, because they’re arguably the most dazzling pieces written for solo cello since Bach.

Not that Weinberg would have cared very much. Of all the factors that contributed to his obscurity, of which Russian anti-Semitism was certainly one, the most puzzling was his lack of interest in promoting his own music. ‘So long as I am writing, the work interests me,’ he once said. ‘When the piece is finished, it doesn’t exist anymore. Its fate (whether ostracization by the Philharmonic Societies, lack of performances, silence in the press, scorn from the music critics) is all the same to me.’ It’s hard to make sense of this claim when you consider the overwhelming generosity of his music: all those melodies that delight the listener by dancing and twisting in the air. The writer Norman Lebrecht, not an easy man to please, says that if he goes for a month without the company of Weinberg, he feels the loss. I wouldn’t know: since my shamefully late discovery of Weinberg, I haven’t been able to stop listening to him.

It’s hard to believe that this elusive man, who until the 1990s was relegated to a walk-on part in biographies of Shostakovich, really thought that his music didn’t matter once he’d written it. I think he just meant it didn’t matter to him anymore, so pressing was his urge to create the next piece. In a letter to his wife in 1966, he wrote that ‘to be a composer isn’t a pastime; it’s an eternal conversation, an eternal search for harmony in people and nature. It’s a search for the meaning and duty of our short-lived existence on the earth.’

It’s possible to be a great composer and not find that meaning: Mahler comes to mind, and also the chronically haunted Shostakovich. But Weinberg appears to have done so. At the end of his life 25 years ago he took what must have an extremely difficult decision, one he never mentioned publicly; it understandably caused distress to some of his friends and has been insultingly brushed aside by a few commentators.

The words on his gravestone read: ‘He that believes in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live’. They are from the Gospel of St John. Although Mieczysław Weinberg’s music radiates pride in his heritage, he never practiced the Jewish faith; instead he spoke of his sense of God as ‘a sort of chorale that has been wandering around with me.’ Two months before the end, that wandering led him to a declaration of faith, and when he died it was as a Russian Orthodox Christian.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2021 World edition.