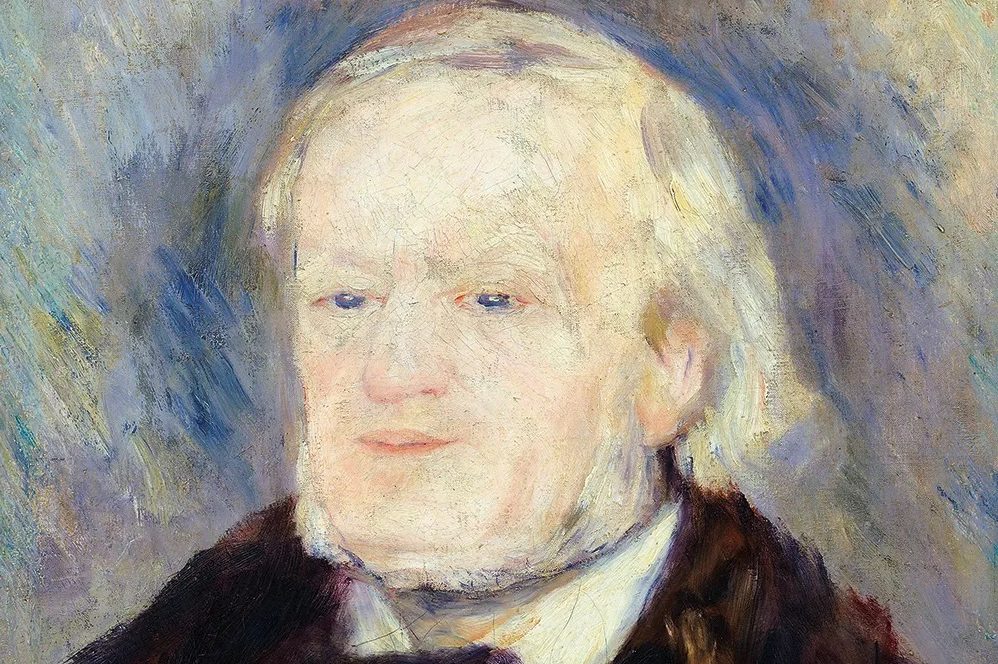

No surprise: the greatest musical experience of my life was Parsifal at Bayreuth in 1962. I thought at the time that I would never again be so moved by a performance of anything. I have kept an open mind ever since, and still it takes me no time or effort to answer the question. Obviously I can’t discuss here why I regard Parsifal as a supreme work, but even if I thought that Wagner had written greater ones, or that some other master composer had — in fact, I do think there are several works by four composers that are as great as Parsifal, though at that altitude rankings and comparisons become absurd — what I experienced in Bayreuth that year was unique and unpredictable.

One of the things that made the Bayreuth experience exceptional, which is wholly missing today, was the town itself. It was extremely provincial and charming at that time, without a university and lacking the hotels (that are actually conference centers) with which it is now swamped. When you booked tickets for the festival in the 1960s, you also booked accommodation, and a friend and I were allocated a room each in Tannhäuser Strasse 17, behind the Festspielhaus. Anja Silja, early in her career and with waist-long hair, was staying downstairs, and was shockingly informal in clothing and manner. There was an atmosphere, wholly missing nowadays, of friendliness and informality: in the intervals we walked into the area marked ‘Only for artists’ and lined up with the performers for beer and sausages. None of that is an artistic experience, but it indicated what people had really come for, in a way that nothing now does.

Anyway, it was the first performance of Parsifal that year. As is still the case, the lights went down, you couldn’t see the conductor enter, thanks to the covered orchestra pit, and — certainly if the conductor was Hans Knappertsbusch, arch-Wagnerian, as it was on that occasion — after an indeterminate time the Prelude began. This was the period when Wieland Wagner’s revolutionary production of Parsifal, unveiled in 1951 and modified each year, was still going strong. It was characterized by the predominance of lighting of extraordinary subtlety and evocativeness, and very little scenery. Wieland may have inaugurated an era in operatic production, but he imposed no, or very little, interpretation on the works, presenting them as beautifully as possible, so that the experience really was a unified and elevating one.

The cast that year was mainly excellent, above all thanks to the glorious singing and acting of Hans Hotter, my operatic and song idol over many years. He sang Gurnemanz, an Evangelist-type role, but with economical and moving gestures. The rest of the cast was adequate, the conducting — as can be heard on the Philips recording from that year — transcendent. Act I was, as it is likely to be, or was until the incursions of Regietheater, extraordinarily moving. After the hour-long interval we trooped back, expecting Act II to begin, but instead we had to wait for about 20 minutes. There was no announcement, but finally the lights lowered and the remarkably unpleasant Act II began. Kundry, the only female role in the drama, has only a small part in Act I, but an enormous one in Act II. Act I’s hadn’t been impressive, but the scream at the start of Act II was terrifying, and clearly that of the — to me — greatest Wagnerian soprano of the time, Astrid Varnay. She set Parsifal (the mediocre Jess Thomas) on fire and the result was an Act II such as I have never heard — incandescent and frightening.

The usual transition from Act I to Act II is one I can find hard to adjust to, the music of the two being so different and in the case of much of Act II downright ugly. In that single performance the issue didn’t arise; it was so intense and involving. When we got to the bottom of the stairs after Act II — no applause in those days for any of the acts, at Bayreuth or elsewhere — we saw a small typed notice stating that the announced Kundry had had a nervous collapse in the interval, and that, at no notice and two years since she had sung the role, Astrid Varnay had been called from her hotel and sung and acted — and how! — the role.

That performance wasn’t saved: if it had been it would be one of the sensations of Wagner performance history, and the most riveting Act II Knappertsbusch had ever conducted. Still, the level of inspiration was maintained in Act III, Wagner’s greatest achievement, and the performance remains unforgettable, as some of my patient and weary friends will agree, having heard me fail to forget it.

This article was originally published in

The Spectator’s 10,000th UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.