In January 1804 the West Indian island of Saint-Domingue became the world’s first black republic after the slaves toiling in the sugar fields rose up against their French masters and, at the end of a thirteen-year insurgency, proclaimed independence. Saint-Domingue was renamed Haiti (an aboriginal Taino-Arawak Indian word meaning “mountainous land”) and the Haitian flag created when the white band was solemnly removed from the French tricolore. Haiti’s is the only successful slave revolt in recorded human history. It was led by Toussaint Louverture, a Haitian former slave himself and emblem of slavery’s hoped-for abolition throughout the Americas.

Thousands of French settler colonists were massacred during the Louverturian struggle. The prospect of a free black state founded on the murder of its white community horrified Napoleon. Saint-Domingue, “the pearl of the Antilles,” was too valuable a colony for the First Consul to lose. Ancien-régime France owed its maritime prosperity to commerce with its great Caribbean dependency, whose cane plantations produced more sugar than all the British West Indies together.

The new French republic could not flourish overseas unless slavery was reinstated, Napoleon reasoned. In the winter of 1801, in flagrant violation of the principles of the French Revolution, he organized an expedition to overthrow the upstart “gilded African” Louverture and destroy the “new Algiers in the Caribbean.” Louverture was abducted from the bright exalting sunlight of the West Indies and shut away in a dungeon in the Jura mountains of France, where, in 1803, he died of pneumonia, aged sixty. He did not live to see the proclamation of the Haitian republic after yellow fever had devastated the French armies and put paid to Napoleon’s dream of a New World empire in the Caribbean. (“Damn sugar, damn coffee, damn the colonies!” fumed the Corsican.)

The aftermath of these revolutionary convulsions is the subject of Paul Clammer’s superb life of King Henri Christophe I of Haiti, who rose to prominence under Louverture but went on to rule in a climate of titanic if not deranged grandeur. In 1820, harried by a mutinous staff and enfeebled by a stroke, Christophe took his own life with a shot through the heart with a silver bullet (so it was whispered: the facts are questionable).

In his nine years as monarch he was determined to prevent a return to slavery under the French, and to that end he built a gigantic garrison fortress on a mountain top in the north of Haiti. Twenty thousand Haitians were said to have perished during the construction of the Citadel after Christophe sent them back to work in conditions of virtual servitude. Wagon axles were mortised into the bastions and worker-slaves were seen to spiral to their death over the ramparts, carrying hods of mortar. The Citadel, a pharaonic folly on a par with the Alhambra in Spain or the Taj Mahal, remains an architectural wonder of the West Indies.

Napoleon was not the only threat. In the south of Haiti the predominantly mixed-race population had broken free of Christophe’s kingdom to found a republic of their own. Haiti in the early nineteenth century was thus divided into two mutually hostile realms — a black monarchy under Christophe in the north and a mulâtre republic in the south under President Alexandre Pétion and his successor Jean-Pierre Boyer.

Christophe, the model for Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones (the play was originally titled The Silver Bullet), nevertheless was a forward-looking sort of autocrat, Clammer argues. Born into slavery in Grenada in 1767, he kept up a correspondence with William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson, as it was through these and lesser British abolitionists that he hoped Britain might recognise Haitian independence. Without the Royal Navy’s protection, moreover, there was no guarantee that the freedom Toussaint Louverture had won for his enslaved peoples might endure.

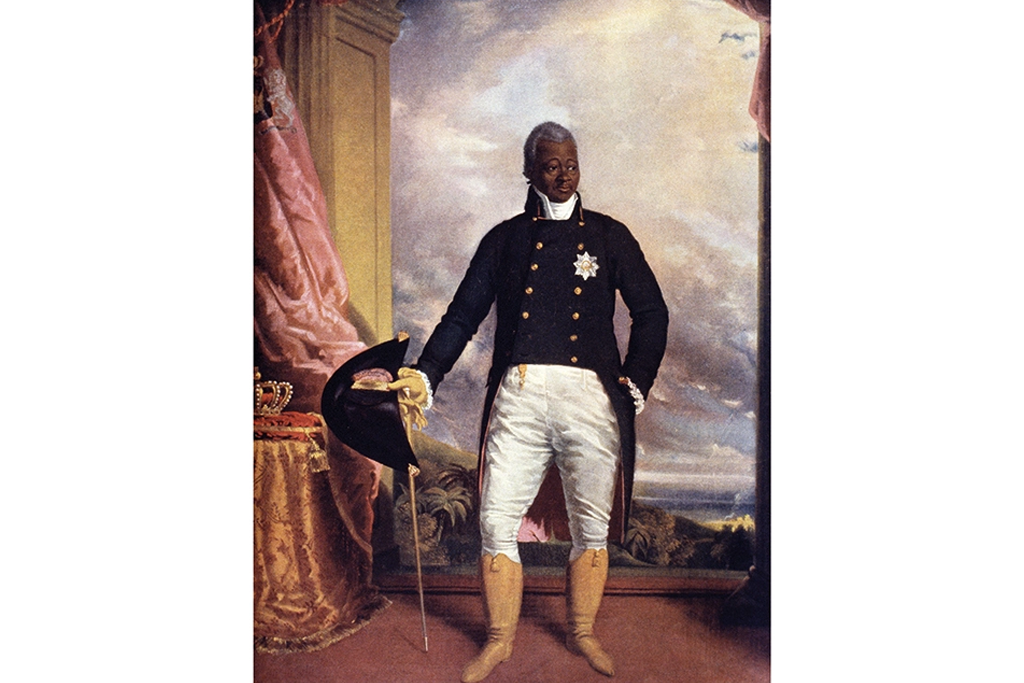

In pages of scrupulously researched history, Clammer rescues Christophe from the ideological and political distortions that often misrepresented him in the past. When O’Neill wrote of his African-American fantasy dictator Brutus Jones that “there is something not altogether ridiculous about his grandeur,” he was surely thinking of the portrait of Christophe that hangs today in a museum in the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince. Painted in 1816 by the English portraitist Richard Evans, it shows the Caribbean ruler as a heavy-set man with a powerful barrel-shaped chest, dressed after his hero King George III of England in a royal blue cutaway coat and white knee-breeches. In a bid to anglicize his domain in the north, Christophe set up a state printing press, a judicial system, a sovereign court with a hereditary nobility and a number of schools administered by the British. His ambition to educate a people newly emerged from the nightmare of slavery showed a visionary spirit at work.

On Christophe’s suicide, his widow Marie-Louise and daughters Améthyste and Athénaïre sought refuge, first in England with abolitionist friends of Wilberforce, then with Capuchin friars in Pisa, where they subsequently died, pretty well forgotten. Meanwhile, President Boyer took power, a venal and corrupt individual who quickly sent Haiti to Hades in a handbasket. With narrative verve and a deep understanding of the country’s extraordinary past, Clammer opens a window on to the life and times of one of the most tragic figures of the francophone Antilles, le roi Christophe.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.