This article is in The Spectator’s January 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.

Somehow it’s fitting that in the era of Donald Trump, the blaxploitation genre, which emerged from the black nationalist movement during the original call for ‘law and order’ during the Nixon administration, has been making a comeback. In 2018, Sony released a remake of Superfly starring Trevor Jackson as pusherman Youngblood Priest and directed by Director X. But perhaps no film has done more to signal the revival of the blaxploitation genre than the latest Shaft film.

The franchise could scarcely appear hardier. It was Gordon Parks who first adapted the film from the works of the pulp novelist Ernest Tidyman. Tidyman conjured up a world of black pimps, strippers and gangsters who took it to the Man. His title, Shaft, accorded with widely held assumptions about the priapic foundations of black manhood. But if the film — and the title itself –– reveled in the libidinous world of the OG, it was also the new fusion of funk and soul with orchestral arrangements that also proved revolutionary. Perhaps no one did more to celebrate the image of black sexual potency than Isaac Hayes, the soul singer who wrote and performed Shaft’s orchestral funk soundtrack about the ‘black private dick/ That’s a sex machine to all the chicks’.

Last June Richard Roundtree, the original Shaft, appeared in the latest Shaft with Samuel L. Jackson, who played Shaft’s nephew in John Singleton’s 2000 Shaft remake, and Jessie T. Usher, here playing Shaft’s grandson J.J. While some of us may marvel at Shaft’s staying power, others recoil from Shaft the elder’s retrograde views about women, gay people and sex.

Whatever his shortcomings, at least this chauvinism and machismo is true to the brash spirit of the original, a ‘complicated man / Who no one understands but his woman’. More perplexingly, the new movie recycles the original Shaft theme but includes no new music from Hayes’s archive. His son Isaac Hayes III has somewhat hyperbolically called this a ‘cultural disaster’.

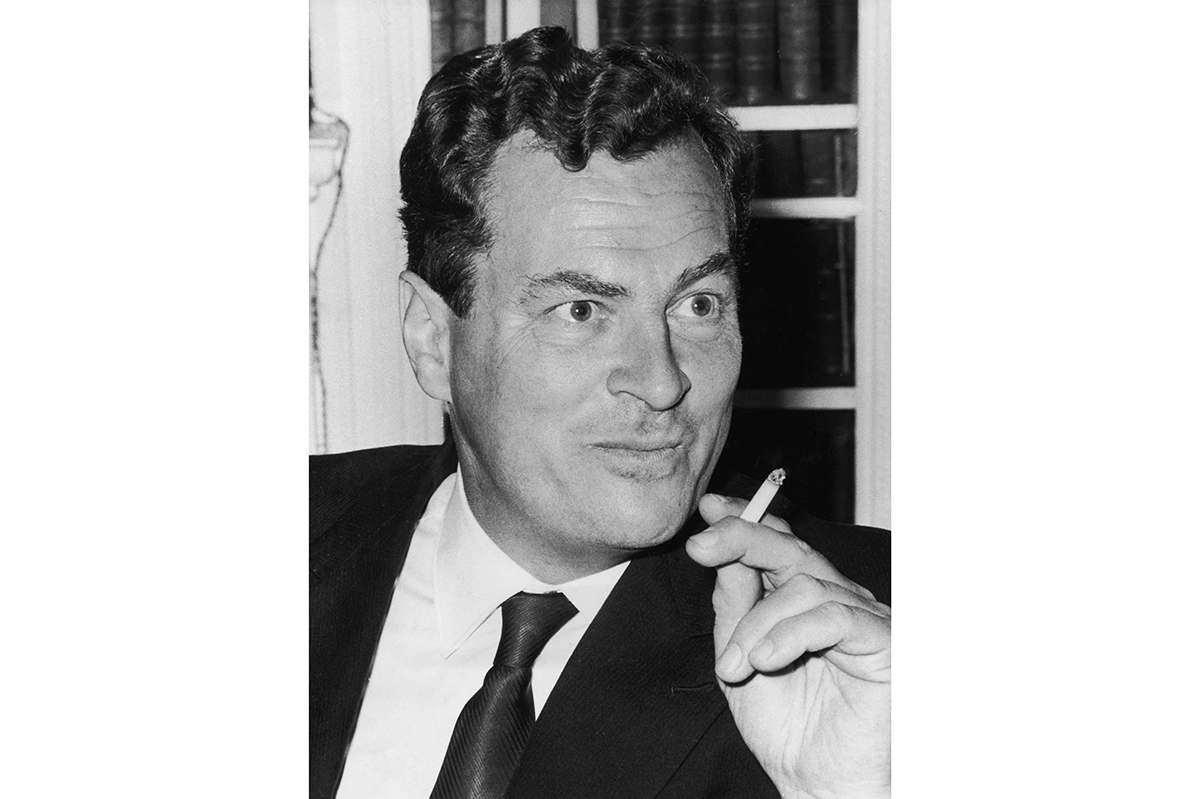

Hayes first made his name as producer and, with David Porter, songwriter at Stax Records in Memphis, where they wrote a string of hits for Sam & Dave, including ‘Hold On, I’m Comin’’ and ‘Soul Man’. In 1969 Hayes’s second solo album, Hot Buttered Soul, rocketed to the top of the charts. It remains legendary for the Bar-Kays’ extended jams on ‘By the Time I Get to Phoenix’ and ‘Walk On By’. In 1971, Hayes’s Shaft soundtrack displaced John Lennon’s ‘Imagine’ as Billboard’s number one. The theme song won Best Original Song at the Oscars, too.

‘At last we have a black hero of James Bond stature in John Shaft,’ Hayes explained. ‘Shaft looks at things from a black point of view. It tells it like it is.’ So did Hayes. As Emily Lordi wrote in the New Yorker in October, Hayes, who was born in a tin shack in Covington, Tennessee, ‘helped to register black voters in the South, pushed for greater black representation at Stax, and co-founded a group called the Black Knights to protest police brutality and housing discrimination in Memphis.’

The lubricious Shaft theme steals the show with its pulsing bass line, shimmering cymbals and crackling wah-wah guitar. But ‘Soulsville’, where Hayes echoes Rousseau’s observation that man is born free and everywhere in chains, might be more powerful: ‘Black man, born free/ At least that’s the way it’s supposed to be/ The chains that bind him are hard to see/ Unless you take this walk with me.’ Stax released the Shaft double album with a large poster of Hayes wearing dark sunglasses and a striped, vaguely Biblical robe. Perhaps it should come as no surprise that Hayes’s next album was Black Moses, a sobriquet that Hayes liberally applied to himself and was the nickname of the antebellum conductor of the Underground Railroad Harriet Tubman, herself the subject of the new movie Harriet, starring Cynthia Erivo. Hayes was nothing if not bold: his stage outfits included a gold chain suit and he drove around Memphis in a 1972 Cadillac Eldorado trimmed in 24-karat gold and lined in white fur.

Hayes, who became a Scientologist in the 1990s, achieved further unlikely fame as the voice of South Park’s innuendo-dispensing Chef before dying in 2008 at the age of 65. His sound lives on. Hayes samples underpin Beyoncé’s ‘6 Inch’ and Kodak Black’s ‘Transportin’’. A recent episode of the NBC series Bluff City Law set its tone with Hayes’s ‘Do Your Thing’. Eddie Murphy’s new comedy vehicle, Dolemite Is My Name, features three of Hayes’s former musicians: Willie Hall on drums, Michael Toles on guitar and Lester Snell on piano.

As Ahmir ‘Questlove’ Thompson of The Roots writes in the liner notes to Craft Recordings’ Shaft reissue, Hayes’s success forced every black-themed film after Shaft to have an ‘accompanying soundtrack by an artist trying to put the black experience on wax’. To return to Hayes’s music isn’t to enter a sterile time capsule, but to listen to a musical wizard whose sonic alchemy seems almost as virile now as when it was originally produced.

This article is in The Spectator’s January 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.