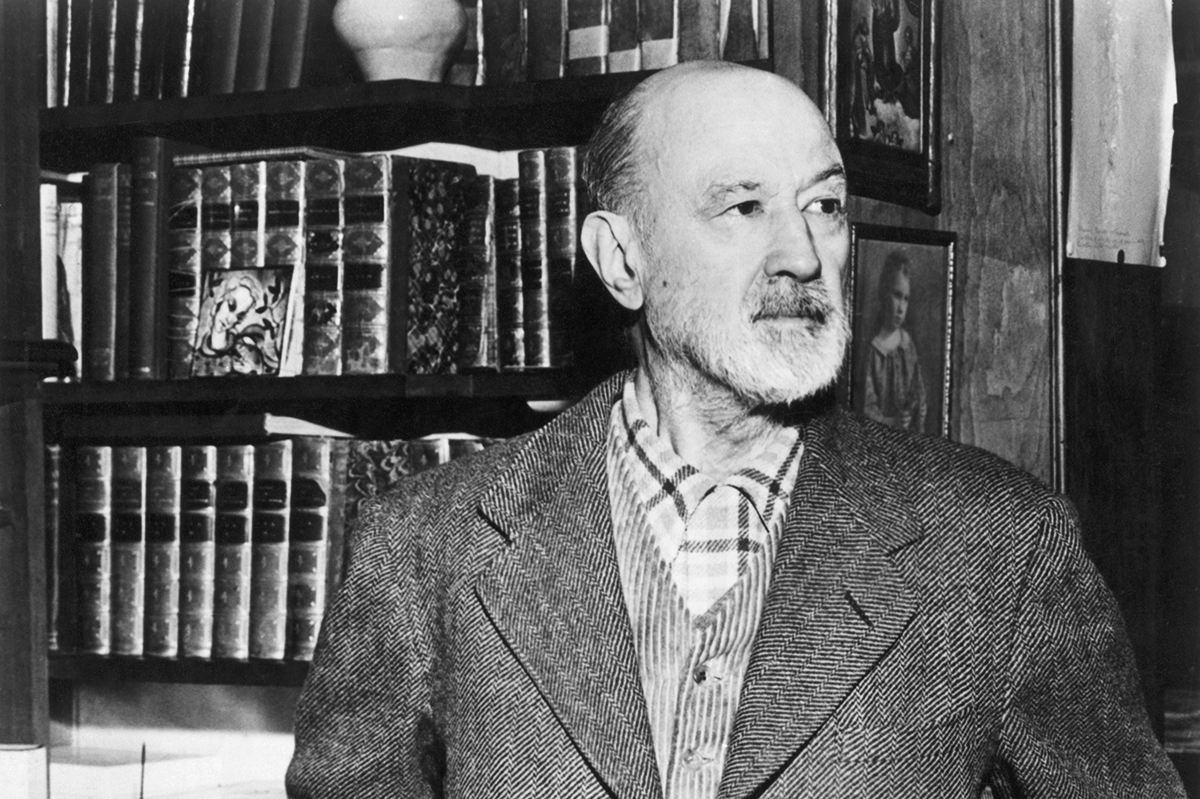

Dr John called James Booker ‘the best black, gay, one-eyed pianist New Orleans has ever produced’. Booker died in 1983, aged 43, ruined by drugs, drink and madness, and attended by legends of delinquency lurid even for a New Orleans piano ‘professor’. Though he had appeared on plenty of other people’s records and stages, Booker had recorded only three studio albums in his lifetime. Classified, recorded in October 1982 and now re-released on vinyl, was the last of them. It might not be the best of them, but it shows why Booker was one of the greats.

The studio was booked for three days, but Booker had a breakdown the week before and couldn’t get a good take down in the first two days. He revived on the third day and recorded the 12 tracks of Classified in four hours. He sounds dazzling and devious, mournful and ecstatic, lyrical and doomed — and frequently all at the same time.

The New Orleans professor plays southpaw-style, leading with his left. The left hand pumps the rhythm and the chords, jumping between bass notes and lower-mid-range chords in the ‘stride’ style, or rocking the ‘shuffle’, the boogie that is written down as a dotted feel but is forever about to tip into triplets. The right hand plays the melody and the solo and, among serious professors, another layer of mid-range ‘comping’. The effect is a flamboyant four-handed blues.

Booker has a clear aural signature, and not just because he alternates virtuoso blues with almost parodically perfect novelties like ‘Warsaw Concerto’. His left hand pushes the rhythm bass notes with anticipatory octaves and arpeggiates thick mid-range chords in a crisp strum. His right is behind the beat, with triplets and ornaments tumbling out of four-note block chords. He cuts up and down the stylistic tributaries of New Orleans piano: to Professor Longhair and Fats Domino, the fathers of the Fifties’ rocking style; before them to ‘Tuts’ Washington and Jelly Roll Morton; back even to before there was jazz, and New Orleans’ piano meant the creole style of Louis Gottschalk, who crossed the bamboula rhythm with French salon music.

Booker is no museum archivist, but he knows the forms. He opens ‘King of the Road’ in solo New Orleans style, with a torrential obbligato, in this case one that nods to ‘Eleanor Rigby’. He understates his moaning vocal with strict chords, percussive and high-stepping, then erupts into a ten-fingered finale, foot jammed on the sustain pedal as he howls ‘I’m a man of means’ with rising desperation, before subsiding into ‘I’m King of the Road’ in a yodeling sob. ‘Alright?’ he asks the producer. ‘A little different?’

James Carroll Booker III’s father was a dancer turned Baptist minister, and his mother was a church singer. At nine, Booker was hit by an ambulance and nearly lost a leg; hospital morphine began his addiction. He studied piano with ‘Tuts’ Washington, the last of the old-time professors who was still knocking it out in the bar of the Pontchartrain Hotel, but he also memorized solos by Erroll Garner, Chopin and Liberace. In 1962, Booker had a hit with the drug-themed ‘Gonzo/Cool Turkey’, then spent the rest of the decade with touring bands, including those of B.B. King and Aretha Franklin.

In 1970, Booker’s drug habit led to a year in the notorious Angola jail. Around this time, he lost his left eye. The recent documentary Bayou Maharajah recounts the stories. Perhaps the eye was removed with a spoon during an accounting dispute with a dealer in Harlem, or perhaps in Angola. Perhaps it was removed by record producers, as Booker sometimes said; but probably not, as Booker told Dr John, by JFK; and certainly not, as Booker replied when asked about his star-shaped eye patch, by Ringo Starr.

Booker’s star rose through the Seventies, despite his deepening drug and alcohol problems. In 1973 he recorded The Lost Paramount Tapes with Dr John’s band. After a show-stealing set at the 1975 New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, he recorded a second studio album, Junco Partner, for Island Records and began touring Europe.

In Europe, Booker played in concert halls as well as clubs. European audiences grasped the range of Booker’s playing because they knew Louis Gottschalk as well as Dr John. Some of Booker’s European shows have become posthumous live albums, almost all of them reflecting his talent better than the studio albums do. Other European shows, such as his tremendous gig at the 1978 Montreux Jazz Festival, can be seen on YouTube.

At Montreux, Booker slips from the stride lament Jelly Roll Morton’s ‘Winin’ Boy Blues’ (1938), which Booker had recorded that year for the soundtrack of Louis Malle’s Pretty Baby, into the rapid blues ‘Pixie’. Then, Booker, who had a habit of incorporating Beatles’ tunes into his gambits, opens a medley with an expansive, lazy ‘Penny Lane’ in which the moving bass decouples from Liverpool brass bands and returns to New Orleans funk. Back on his turf, he delivers a swinging ‘I Saw Her Standing There’ in which he turns McCartney’s predictable vocal phrasing against the rhythm, then segues into one of his own, ‘One Hell of a Nerve’.

He even appeared in Leipzig, East Germany, after smuggling his marijuana through the Iron Curtain in his curly wig. But Booker, like most black jazzers in the Seventies, couldn’t get arrested back home — unless it was for narcotics. Luckily, the New Orleans DA was a fan. In lieu of jail time, he sentenced Booker to teach piano to his young son. The boy’s name was Harry Connick, Jr.

Half of the dozen tracks on Classified are solos, and half are with Booker’s trio from his regular spot at the Maple Leaf Bar in New Orleans. Most of these tracks are New Orleans standards (‘One for the Highway’, ‘Tipitina’) or staples of the bar- room setlist (‘Angel Eyes’, ‘Hound Dog’). All are transmuted by Booker’s inspired subversions. The bump and grind of ‘Lawdy Miss Clawdy’ becomes an unrequited solitary stroll. Professor Longhair’s theme ‘Tipitina’ is sheared of its right-hand flourishes and reduced to a two-fisted rhythmic hammer. On ‘Angel Eyes’, Booker tears off a double-time, single-note solo phrase that lasts 14 bars, an appoggiatura on every other note in a neurotic parody of genius. On the closing-time ballad ‘If You’re Lonely’, he deliberately stumbles his right- hand rhythm against his left and leans on his impeccably steady trio like a drunk.

Booker was to Professor Longhair as Oscar Peterson was to Teddy Wilson or Nat Cole among swing pianists. Aided by classical training, Booker had the manual technique and imaginative stamina to summarize his inheritances and expand them. He accepts the virtuoso’s invitation to elaboration and the showman’s challenge to exhibitionism but, unlike Peterson or Art Tatum, he takes complexity as the scenic route to simplicity.

Peterson broadens the blues palette by expanding the harmonies through chordal substitution. Booker collapses the form. On ‘All Around the World’, Booker extends the ‘turnaround’ (a two-bar transitional sequence at the end of a section or chorus) into a repeated vamp, to expose the secret of the blues: the deceptive simplicities of the groove and the blue note. Booker takes the venerable ‘Baby Face’ — written, incredibly, in 1926 — faster than Fats Domino. He cuts its solo section down to two chords, then smashes out a high-speed ‘Lady Madonna’, four-to-the-floor with his left hand while the drums play a rhumba cross-rhythm.

‘Madame X’ with chromatic substitutions, Booker plays it straight and steady in the left hand, faithful to the ‘Spanish’ rhythm and changes. But his right flies around the upper keyboard, ornamenting not just the opening note of each phrase, but frequently also the closing note, and sometimes even a piquant note or two in the middle too. With a lesser sensibility, this rococo Spanish blues, light and airy as Tiepolo’s last ceilings in Madrid, might topple into camp. With Booker, we float away on his suspension of his disbelief.

It is a cliché that the blues should be played in mortal dread. In Booker’s case, this was no more than the truth. Until his mother gave him a saxophone, he aspired to join the priesthood; throughout his life, he would join his aunt Betty and her family at the St Rose de Lima church and accompany the choir. He was tormented by his addictions and his sexuality, and bound to a boundless talent. There is a hysterical jollity to his playing, a whistling past the graveyard.

On the final track, ‘Three Keys’, Booker exhumes the double roots of New Orleans piano in the rhumba creole of Louis Gottschalk. Each jerky change of key opens up a new vista. The music, like the river, will roll on forever, but the player is breaking down.

Booker disappears from sight and sound in a solo spot at the Maple Leaf, recorded for television a month before he died. The two-chord vamp ‘Papa Was a Rascal’ swings between minor sorrow and major exaltation with the desperate self-knowledge of the addict, but Booker follows it with the comically cheerful ‘New Orleans Piano Blues’. He executes the mock-Chopin theatrics of ‘Warsaw Concerto’ like a farewell to the world — only to change his mind and segue into a cakewalk. It is the setlist of a man unsure whether to live or die.

‘The Bible tells you are guaranteed to live to 70 if you do the right thing,’ Booker informs the drinkers in one of his erratic between-song improvisations. ‘My mother wasn’t no junkie. She died when she was 53.’

Booker was to play one more gig at the Maple Leaf, to five people. The night before his death, he failed to show for another date. He died in a wheelchair, waiting for the emergency room.

James Booker’s Classified is remastered and reissued by Craft Recordings. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2020 US edition.