The once-explosive accusation that a rock ’n’ roll band is a sell-out, aimed at artists who make an accommodation with industry, has come to seem a little naive since it was first bandied about in the 1960s. Whether it’s that well-known monument to prudence Iggy Pop extolling the virtues of car insurance, the Zombies promoting Tampax or Bob Dylan shilling for Victoria’s Secret, they’re all at it these days. Elton John wants you to dial UberEats, the Stones will start you up with a $139.99 Keurig coffee machine, and by now it might be easier to list the names of rock stars who haven’t chugged Pepsi on TV than those who have. And you’d have to go even further back than the Sixties — Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 110,” in fact — to find the definitive lament about the corrupting marriage of art and finance:

Alas! ’tis true, I have gone here and there

And made myself a motley to the view,

Gored mine own thoughts, sold cheap what is most dear,

Made old offenses of affections new.

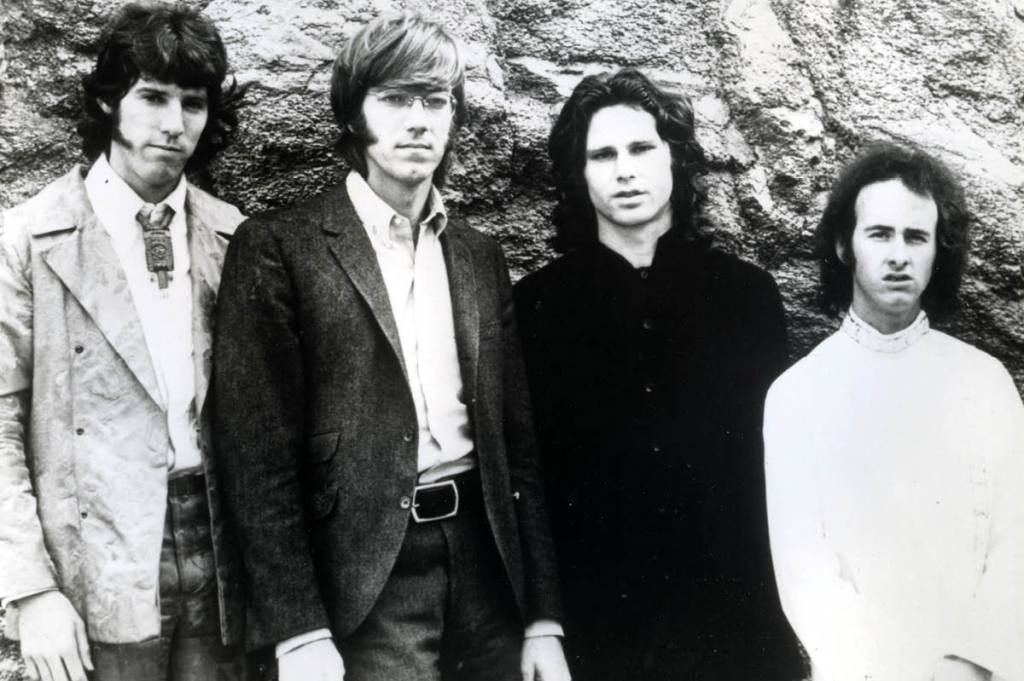

All of which brings us to the strange case of the Doors’ drummer John Densmore and his protracted legal battle against his former workmates about their appropriation of the band’s name. You may remember the group: in addition to the superbly proficient Densmore, there were the cloudy-haired Robby Krieger and Ray Manzarek, looking like a hip chemistry professor, on guitar and keyboards respectively; and up front, Jim Morrison, at least in the early days a pop Adonis in leather pants and silver concho belt, with a baritone howl that sounded like Frank Sinatra on quite a lot of acid. Between them they specialized in not so much songs as in edgy sonic pastiches like “Riders on the Storm,” “Strange Days” and the twelve-minute psychodrama of droning fairground organ, hypnotic drums and disturbing vocal interjections they called “The End.” Morrison died in July 1971, officially of a heart attack, although as usual on these occasions hardcore fans continue to insist that the real cause of their hero’s demise lies buried somewhere back among the chaos of his twenty-seven years alive, or for that matter that he faked the whole thing and is even now residing among the Navajo of rural Arizona.

“There was Jim, the wildly creative guy who couldn’t play a note of music but who heard whole concerts of stuff in his head,” says Densmore, still exasperated by the thought more than half a century later. “And then there was this other character I called Jimbo, a kamikaze drunk who came close to squandering the whole thing by behaving like a Skid Row bum.” Morrison always had a penchant for confronting his audience, but toward the end he seemed to be increasingly channeling his inner Benny Hill by shedding his trousers onstage or telling excruciating jokes about a blind man confusing a fish for his girlfriend. Some of his other concert repartee was even less elevated.

“We got to our final show at New Orleans in December 1970,” Densmore remembers. “It was a full-on Jimbo performance. He was cracking terrible jokes, rambling on as the three of us tried to get a song started. You could hear the audience groaning. Finally, I counted in ‘Break On Through,’ and we somehow fumbled through the rest of the set. It was a total embarrassment, and later I just turned to Robby and Ray and said, ‘That’s it. We’re not going out on the road with that lunatic again.’ Nowadays you’d try and get him into therapy. I’m sure Jim could have cleaned up with professional help. Why not? He was a smart guy. But we badly needed a break.”

Densmore wasn’t alone in his conviction, because just three months later Morrison left for Paris in an attempt to write poetry, address his health issues and generally decompress. He wasn’t completely disassociated from the demands of his career, however, because a few weeks later he called Densmore out of the blue to enquire about the sales progress of the Doors’ latest album L.A. Woman. “I told him it was going great, and he said that was cool, and perhaps we should get together and do another one. Maybe Jim could have cleaned up his act and come back, but we’ll never know. That was the last any of us heard of him until we got the call saying he’d gone.”

It’s hard not to rapidly warm to Densmore, who seems to have settled for the role of a wise elder statesman of rock ’n’ roll, equally willing to celebrate its highs and to wryly enumerate its lows. In the latter category there are stories about the Doors fans who crossed over from mere respect for their idols into the less edifying realm of obsession. “We had a guy who hung around our studio in LA who liked to burn his tongue with a cigarette in order to sound like he imagined Jim did.” Of the group’s brief attempt to continue as a three-piece following Morrison’s death, Densmore notes, “In retrospect, it was probably too much to hope that the soufflé could be made to rise twice.” And there’s his surely definitive comment on the essential dynamics of any working rock band, which he summarizes as “like polygamy without the sex.” Quite a few drummers seem to have something of a gift for deadpan comedy. Perhaps it’s to do with the timing.

More importantly, Densmore has also made a name for himself as one of the keepers of the original spirit of 1960s artistic integrity. “Making a living is one thing, but I never wanted to be part of a culture that celebrates ostentatious consumerism,” he says. In a modern pop landscape where some degree of corporate sponsorship is the rule, and total freedom of expression the exception, these words might seem quaintly archaic. But Densmore had at least one principled ally in the Doors lineup.

“It all started in 1968 when Buick offered us $75,000 — huge money at the time — to sell its new model. Robby, Ray and I agreed to it while Jim was out of town. He came back and went nuts. Or, being Jim, what he actually said was that if they aired the ad he would smash up a Buick on live TV with a sledgehammer. A bulb went off over my head at that moment. What a fantastic response, I thought. It’s one of the reasons I still miss Jim, if not Jimbo, to this day.”

In time, Densmore’s stand on licensing the recordings for commercial use would plunge him into a quagmire of litigation against his surviving bandmates, two personally amiable breadheads who saw no reason not to continue to tour under the Doors name, nor to license their music to another car firm for a cool $15 million. Some of the ensuing courtroom exchanges were as surreal in their way as any of Morrison’s more out-there lyrics.

“Among other things, they asked me if I was a communist, and whether I supported Al-Qaeda,” Densmore recalls, still sardonically amused by the experience. “As a matter of fact, I like making money as much as the next guy, but as I said to [Manzarek and Krieger]: ‘We’ve all got cool houses and a couple of cars in the garage. How much more of the stuff do you really need?’ They never really had an answer to that.”

In the end Densmore won on all fronts, which made it even less likely that the three surviving Doors would ever call each other up, grab a few session musicians, rehearse all the old hits with Eddie Vedder on lead vocals, and go out on tour again with banker-friendly ticket prices. And sadly the door closed permanently on even a partial reunion when Ray Manzarek succumbed to cancer in May 2013 at the age of seventy-four.

“We made peace right before the end, for which I’m eternally grateful,” says Densmore, who adds he’s also friendly these days with Robby Krieger. “We might even do something together, but I can assure you it won’t be called the Doors.”

Densmore wrote a book about the whole saga, called The Doors Unhinged — it’s out again now, and a terrific read — and donated the profits to charity. “Money is like fertilizer,” he tells me, in another of his striking aphorisms. “When it’s spread around, things grow. When it’s hoarded, it stinks.”

Somehow I feel moved to ask about the Doors’s legendary appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show to promote their song “Light My Fire.”

“Sullivan was in a panic about a line where Jim sings ‘Girl, we couldn’t get much higher’,” Densmore says, chortling at the memory. “He wanted us to change it to ‘Girl, we couldn’t get much better.’ Of course, Jim sang the line exactly as he wrote it. A producer came up to us afterwards, and yelled at us that we’d never play the Ed Sullivan Show again. ‘Hey, man,’ said Jim. ‘We just did the Sullivan show’.”

Perhaps there’s a larger truth about authenticity in the Doors’ story. I’m pretty sure Alice Cooper doesn’t wrap a snake around his neck when he’s out on the golf course, and I doubt Mick Jagger leaps about like Nureyev when he’s making his morning cup of tea. But with the Doors what you saw was really what you got. And that’s a legacy worth protecting.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply