John Freeman’s gorgeously crafted novella, Hit and Run, is a gripping account of a few tumultuous months in a youngish man’s life. It is imbued with a black-and-white, noirish tinge, beginning as a detective narrative, moving through domestic drama and romance and eventually morphing into a ghost story, profitably exploring what these genres have in common. Based on real events, though it isn’t clear which elements are true, it shows how lives can unravel (and ravel) at the whims of fate, and at the same time demonstrates that everything is connected. This is a work about significant moments, about “a piece of time so sharp it carved a human being from existence,” glittering with reflections and refractions.

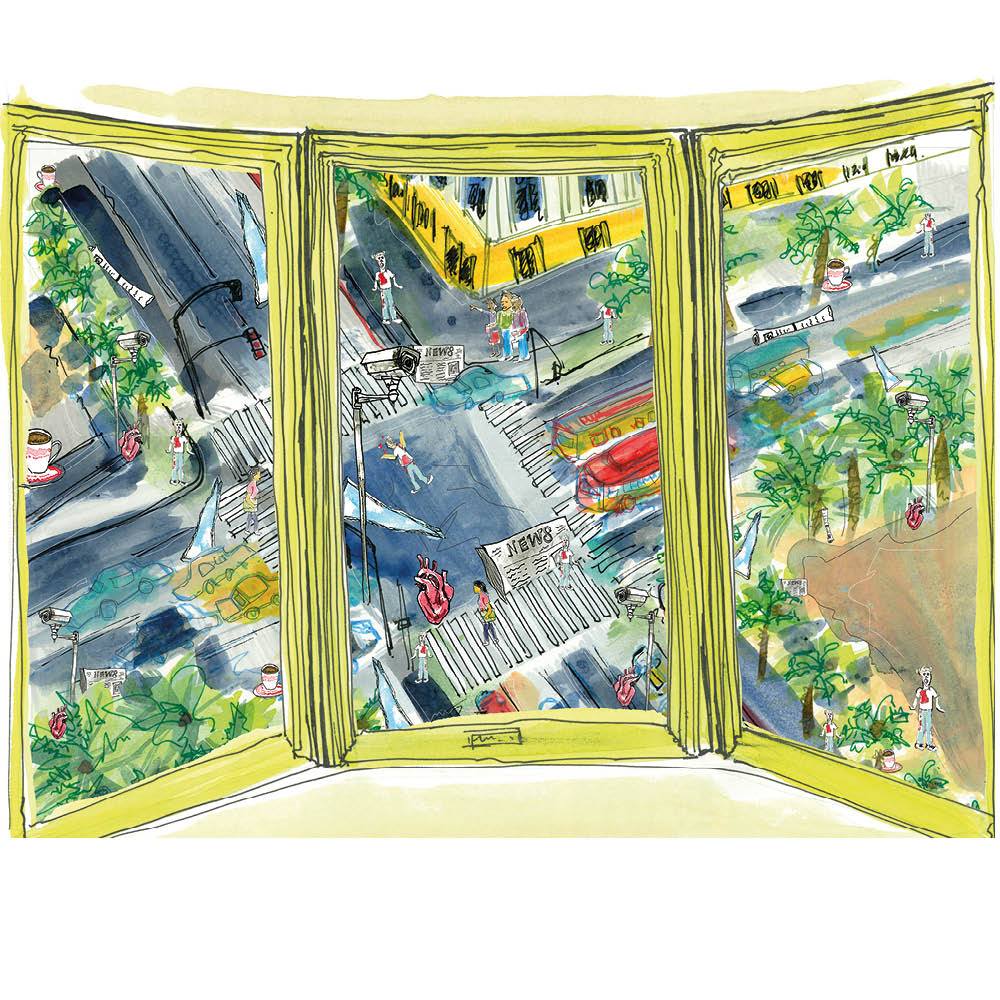

There are many plot strands running through this slim volume, all adroitly woven together, and all with themes of loss and care, change and surveillance at their heart. At the center is John Frederick, presumably an alter ego for Freeman, who appears to have a desirable life in a Sacramento that comes alive with waving palm trees. John Frederick writes for the culture section of an overseas newspaper — the dream! — and is recently married to the beautiful, faintly troubled Linda.

The tragedy that frames the work is what happens to a man called Philip, run down by a speeding driver at an intersection at 3 a.m. John Frederick witnesses it with some friends. The car vanishes; meanwhile, “there was a man splayed out on the center medi- an, a crowd of revelers laughing and teetering and pointing like one of those Hieronymus Bosch paintings.” The Bosch reference hints at the way this terrible event will draw John Frederick into an underworld of the mind, where the “more I grasped at reality, the more it frayed”; significant, too, is the image of the crossroads, places associated with other worlds and a sense that we are all potentially one step away from a life-changing event.

A series of coincidences underlines the novella’s themes: the morning after the accident, when John Frederick and Linda go and get a cup of coffee, Linda leans, unknowingly, against the car that killed Philip. It’s still smeared with blood. This tiny action also links her symbolically to the engine of destruction. The dead man turns out to be John Frederick’s “cousin’s boyfriend’s best friend,” a man everyone loved. Meanwhile, the owner of the car claims his nephew was driving it: attempts to find the nephew fall flat. And the car’s owner turns out to be Russian, which sends John Frederick into paranoia, wondering if at any moment a hitman will turn up at his door. Freeman asks: can we ever find what is true?

The investigation, with which John Frederick actively cooperates, at one point even helping the assistant district attorney look for footage of the accident, runs in parallel to another, as Linda begins spending rather too much time with her muscular personal trainer. John Frederick, racked by insomnia, spends nights working in a local bar and turns investigator himself. Using ethically dubious methods (he installs a keyboard tracker on his wife’s computer), it turns out that in some respects he’s not paranoid — he uncovers evidence that she’s thinking of having an affair with the trainer. This section is particularly tense, moving toward the inevitable confrontation. “We hadn’t even begun to write the thank-you cards for our wedding,” he notes mournfully. Linda comes across as selfish, unkind and fragile, but John Frederick is open about his own failings too.

As their marriage falls apart, John Frederick’s parents’ union is presented, by contrast, as one of remarkable resilience. His mother has been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, and when he visits them, he finds that “their living room has been turned into a full-time care center.” His father is selflessly looking after her: there is a very touching moment when John Frederick leaves and his father holds up his wife’s arm to wave goodbye, as if she were able to do it herself. And yet with powerful honesty, John Frederick admits that he was pleased to depart, and wonders why he is “so much more involved with the murder of a stranger.” The love between his parents is a beacon, even as his mother fails — and it points toward the hopeful part of the novella. This arrives when John Frederick meets the sophisticated Farah and swiftly falls in love with her; their relationship helps keep him from teetering into the underworld. When John Frederick moves into a new apartment, Freeman takes an unexpected turn and executes an absolutely chilling ghost story. Is it John Frederick’s paranoia? Is it the ghost of the dead man? Is he really being followed — or is there something else going on? We never quite find out, which makes it all the more deliciously eerie. Freeman’s writing is impeccable, clean and unfussy, sometimes ornamented with a striking, poetic phrase, marking plot points and alterations in scene and season with subtle compulsion. In the end, justice is achieved, but in an unexpected way. Like a shard of glass, this piece seems light, but will strike its readers deeply.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply