February 15, 1981, the day after Valentine’s Day. At 11 on a Sunday morning, a man’s body was found slumped in the passenger seat of a beige 1971 Mercury on a residential street in the Forest Hills section of San Francisco. All four doors were locked. A Valium bottle was in the pocket of a coat on the back seat. There was no ID: the body went to the morgue as John Doe #15.

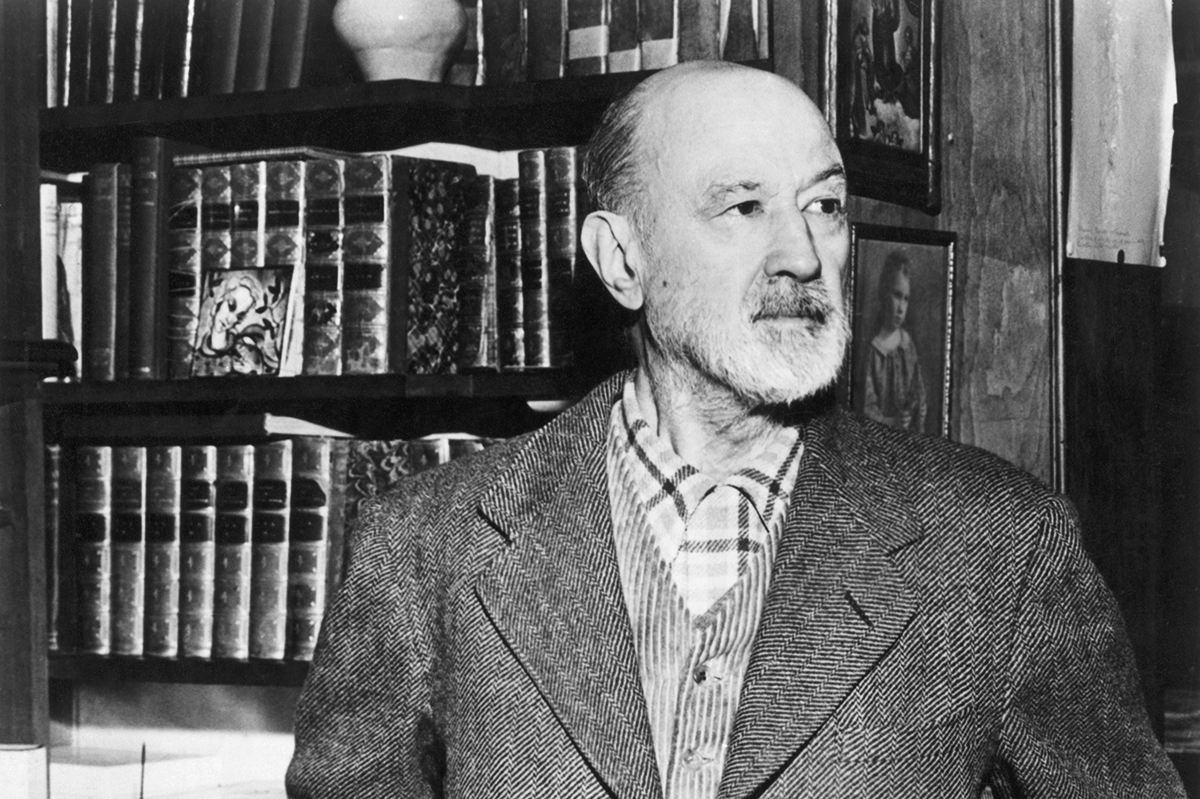

The dead man was 37-year-old Michael Bloomfield, a pioneering guitarist who brought blues to the mainstream and set Bob Dylan’s music alight. The cause of death was registered as cocaine and methamphetamine poisoning. Questions remain unanswered about how he died; why methamphetamine, which he avoided, was in his system; and why he was in a part of town where he knew no one.

Bloomfield’s career was blighted by his fear of fame, lifelong insomnia and undiagnosed bipolar disorder. These issues haunted him like hellhounds on his trail. Some of Bloomfield’s friends claimed the Valium was planted on him. Others think he overdosed on heroin or a synthetic designer opioid at a party, and a panicked dealer drove to the spot and pumped him with cocaine and methamphetamines to wake him. ‘The police inquiry hit a dead end very quickly,’ his producer Norman Dayron recalled. ‘Essentially, a blues musician was found in his car.’

It was a pitiful end for the man who had turned the blues into rock and rewritten the vocabulary of the electric guitar. Bloomfield’s distinctive, fearless, revolutionary and sweet style kickstarted the very idea of a rock soloist and changed a generation’s thinking about music. ‘Whether it was an acoustic guitar, a Telecaster, a Stratocaster, or a Les Paul,’ Carlos Santana said, ‘you heard three notes, you heard one note, you knew it was Michael.’

Michael Bernard Bloomfield was born in 1943 to a wealthy Jewish family and raised in the Chicago suburb of Glencoe. His father, Harold, ran a firm manufacturing kitchen appliances. His mother Dorothy (known as Dottie) had been an actress and model.

‘From the day he was born, Michael was never a conformist,’ said Dottie. It was clear he wouldn’t go into his father’s business once he began playing guitar aged 13. Despite being left-handed, he learned to play right-handed. Later that year, he got a portable transistor radio for his bar mitzvah. The kid who struggled at school and rebelled against his father’s authority found comfort in the black music he heard over the airwaves. Within two years, he was, in his words, ‘a monster’ player.

Soon, Bloomfield was venturing to the South Side with his family maid to black blues clubs. At 17, he was regularly sitting in with blues masters from Howlin’ Wolf to Buddy Guy and Junior Wells. ‘I would go down there thinking I was really some hot stuff, you know, ’cause I had some fast fingers and I had plenty of licks, but I didn’t have no soul or nothing. All I had was speed and some brash Jewboy confidence.’

Muddy Waters had a particular impact on Bloomfield. ‘He was like a god to me,’ he later recalled. ‘I’d hear Muddy’s slide. I’d be tremblin’. I’d be like a dog in heat.’

‘He was a fat little Jewish kid then,’ Bloomfield’s friend Fred Glaser recalled. ‘Muddy would say, “My friend Michael Bloomfield from Glencoe is going to come up here and play the guitar and I want you to listen to him real good, and want you to give him a nice, big round of applause when he finishes. He’s a great musician and a good friend of ours.” And everybody would laugh and say, “Come on, man, get that fucking kid off!” They’d laugh at him. And then he started to play, and they’d shut up… minutes into a song, he started taking off, and people would sit back and listen and start dancing. And they realized he was great. They started applauding him.’

‘When I first heard Michael,’ said Waters. ‘I knew he was gonna be a great guitar player.’ Waters described Bloomfield as his ‘son’, and the pair became so close that Bloomfield would babysit Muddy’s grandkids.

Besides Chicago electric blues, Bloomfield was equally fluent on acoustic guitar. By the time he was 19 he was managing a folk-music coffeehouse, The Fickle Pickle, which he used to search out old bluesmen. ‘He’d find these guys, get out in the ghetto and search for them and get them gigs,’ longterm collaborator and friend Nick Gravenites recalled. ‘While they played, Mike would be there watching their every move, learning at the feet of the master blues stylists of America. This was an extraordinary situation that can never be repeated, and it helps to explain Mike Bloomfield’s mastery of the blues guitar.’ He was also traveling across America with Big Joe Williams. Big Joe had been a notable artist in the Thirties and Forties and wrote the classic ‘Baby, Please Don’t Go’ (covered by the Doors and Van Morrison). The young Jewish kid and the elderly bluesman struck up a genuine friendship. Williams ushered Bloomfield into the company of his fellow bluesmen: ‘I’d say, “Listen, Joe, d’you know where Tampa Red’s living?” Joe would say, “Sure I know where Tampa’s at — I’ll take you right now.”’ The unusual pair traveled to see a variety of the Delta blues masters, including Kokomo Arnold, Lightnin’ Hopkins and J.B. Lenoir.

The dynamic between them was volatile, occasionally violent. In his 1980 book, Me and Big Joe, Bloomfield recalls how a drunken fight in St Louis resulted in Joe stabbing Michael’s hand with a penknife. They separated until a few weeks later, when Bloomfield saw Joe in a bar. ‘Well, Michael,’ Joe said, ‘we really had ourselves a time in that St Louis, didn’t we?’ Bloomfield agreed and played a few arpeggios on Joe’s guitar, before handing it back. ‘That sound good, Michael,’ he said. ‘You play on some.’

‘Joe’s world wasn’t my world,’ Bloomfield wrote. ‘But his music was. It was my life; it would be my life. So playing on was all I could do.’

In March 1964, aged 21, Bloomfield was signed to Columbia by John Hammond, who discovered Billie Holiday and Bob Dylan. But Hammond was unsure how to market Bloomfield because of his lack of singing ability. ‘He could not have competed with the Rolling Stones,’ Hammond reflected. ‘He was no Mick Jagger, but he was a hell of a guitar player.’

Columbia shelved Bloomfield’s early recordings. In early 1965, however, Elektra Records recruited Bloomfield to play lead guitar for the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. They were America’s first interracial blues outfit, with Paul Butterfield on harp and vocals, Elvin Bishop on guitar, Mark Naftalin on keyboard and Howlin’ Wolf’s old rhythm section, drummer Sam Lay and bassist Jerome Arnold.

Then Bob Dylan called and asked him to play on Highway 61 Revisited. Al Kooper, who had been invited to play guitar at the sessions, describes how Bloomfield came into the studio from the rain with a caseless Telecaster and the electroshocked hair he called his ‘Isro’. He sat down, wiped the Tele with a towel and plugged in. Kooper put his instrument down, awestruck.

Bloomfield had no idea what the sessions would hold: ‘No one knew what they wanted to play or what the music was supposed to sound like.’ Dylan, who was searching for a mercurial sound similar to the Byrds, told Bloomfield bluntly, ‘I don’t want any of that B.B. King shit.’ The results changed the course of American music. Highway 61 was one of the defining albums of the new rock genre, and though the lacerating licks that punctuate the end of Dylan’s verse and chorus are in the traditional call-and-response places of the blues, Bloomfield’s playing is powerfully original.

In July 1965 the Butterfield Blues Band played the Newport Folk Festival. Folklorist Alan Lomax introduced them with a diatribe about white boys amplifying their instruments. Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman, who was hoping to manage Butterfield’s band (he later managed Bloomfield), confronted Lomax, and the two wrestled. The hype this created, combined with his growing dislike of folk orthodoxy, convinced Dylan to go electric for his set two days later. He recruited Bloomfield and they assembled a band. Dylan’s set was booed by folk purists.

Little wonder they couldn’t comprehend it. Bloomfield was hunched over his white Telecaster playing spellbindingly fierce lines that were as loud as Dylan’s microphone. Gravenites described Bloomfield’s playing as ‘like a hungry wolverine on a carcass.’ The evening of July 25, 1965 was a turning point in the history of the electric guitar and Bloomfield was the sound of the future.

Dylan asked Bloomfield to stay in his band, but Bloomfield worried he wouldn’t get enough of a chance to play blues and so he turned Dylan down. And play the blues he did — and then some. He showcased his breakneck improvisation and melodic phrasing on Butterfield’s eponymous 1965 debut album. The record brought the blues into the mainstream. When they toured England, Eric Clapton was taken aback, describing Bloomfield as ‘music on two legs’. Watching the band live convinced a young Santana he needed to follow in Bloomfield’s footsteps: ‘It was enough for me to say, this is what I want to do and want to be for the rest of my life.’

The impact of America’s first interracial blues band cannot be overstated. At a time of civil rights unrest, here was a racially mixed band playing deadly serious blues.

But it wasn’t simply what they played that mattered, it was the fact they shone the spotlight on their heroes. Bloomfield convinced legendary promoter Bill Graham to book black artists such as B.B. King. ‘He is wonderful,’ King said of Bloomfield in 1968. ‘Until the days of rock ’n’ roll, a lot of the places would not accept us… But the doors are open now because of people like Mike, Elvis Presley and the Beatles.’

Butterfield’s second album, East West (1966), was equally hugely influential, not least because of the 13-minute Indian-inspired title track that was far removed from the 12-bar blues that dominated at the time. But the relationship between Butterfield and Bloomfield became strained. Bloomfield was also an insomniac, and touring affected his mental health. ‘Michael hated every minute of it,’ his wife Susan Bloomfield said.

These factors, combined with Bloomfield’s desire to make a record with horns, led to him leaving to create the Electric Flag. He recruited singer Nick Gravenites and the bassist Harvey Brooks and pinched future Hendrix drummer Buddy Miles from Wilson Pickett’s band. (Miles would later say that he felt ‘more at home’ playing with Bloomfield than Hendrix.) Augmented by a horn section, they signed to Columbia and debuted at the Monterey Pop Festival of 1967. The reviews were glowing, but Bloomfield was disappointed, describing the crowd’s enjoyment as ‘festival madness’.

Bloomfield was an extraordinary player, but by his own admission he wasn’t an entertainer. Despite being photographed at the festival with Jimi Hendrix and Jerry Garcia looking relaxed, Bloomfield, who had hitherto been considered the greatest player in America, was unnerved.

In March 1968 the Flag released A Long Time Comin’, to mixed reviews. Critics were disappointed to find Bloomfield buried in the mix on the soul numbers that dominate the album. When he steps out of the shadows, however, on ‘Killing Floor’, ‘Texas’ and ‘Easy Rider’, his virtuosity is distinctive. The album should have opened an exciting new chapter, but instead it seeded Bloomfield’s slow decline into obscurity.

A few months after the release of A Long Time Comin’, Bloomfield quit. Together with several band members, he got hooked on heroin. Bloomfield claimed he doped to medicate his insomnia. His marriage fell apart. Shortly afterwards, Al Kooper approached Bloomfield to contribute to a studio jam session. Bloomfield played with Kooper for one day and fled, leaving his old friend with half an album’s worth of remarkable instrumentals. One Coltrane-like raga, ‘His Holy Modal Highness’, went beyond the obvious blues phrasing and showed that, like Hendrix, in his more expansive moments Bloomfield could push boundaries in a way few could. Until then, Bloomfield’s spellbinding playing had mostly been caught in live shows; his studio work, while brilliant, hadn’t grabbed the same lightning bolt. But here, with Kooper, his true virtuosity was caught on record, perhaps for the first time.

Kooper drafted in Stephen Stills to finish the other half and released it as Super Session. It became the best-selling album of Bloomfield’s career, but he dismissed it as a ‘scam to make money’. He wanted to be a bluesman; he disdained popularity. ‘The guy in America at the time was Mike Bloomfield. There was no one else,’ Clapton said of meeting Bloomfield in 1966. ‘You know why? He was serious. There was no bull involved. It didn’t have anything to do with being on TV or showbiz or popularity.’

At the close of 1968, Bloomfield played on Janis Joplin’s I Got Dem Ol’ Kozmic Blues Again Mama! The following year, he recorded a live record, My Labors, with Gravenites at the Fillmore East. It features some of Bloomfield’s finest playing, if not some of the greatest live rock playing ever recorded. Bloomfield also celebrated his close friendship with Muddy Waters on the latter’s 1969 album Fathers and Sons. And he produced and played on Otis Rush’s Mourning in the Morning.

His solo debut, It’s Not Killing Me, also released in 1969, was critically panned. It’s an unremarkable album, with some nice, barroom blues numbers. The failure of the record, combined with a manically busy year, a divorce, exhaustion from touring, producing and playing, and his continuous battle with insomnia, sent Bloomfield spiraling into a deep depression. He quit playing for 18 months and became a full-time junkie.

Distressed at her son’s rapid deterioration, Dottie enlisted B.B. King to bring him back from the brink. With the help of his hero, he picked up his guitar again. In March 1971 he recorded with Woody Herman’s jazz orchestra, on Miles Davis’s recommendation. ‘When [Bloomfield] plays for blacks, his shit comes out black,’ Davis remarked. In 1973, Bloomfield recorded the album Triumvirate with Dr John and John Hammond Jr. In 1976, he made If You Love These Blues, Play ’Em as You Please, which he described as his best record.

As the decade progressed, however, Bloomfield’s output became sporadic and unreliable; there are various records cut cheaply that are best left forgotten. Still, there were worthy moments. Two live recordings from 1977, Shake, Rattle and Blues, featuring Big Joe Turner, and I’m With You Always find Bloomfield in great form. His final record of note, Bloomfield/Harris (1979), was a lovely collection of acoustic gospel instrumentals.

Bloomfield’s father was a depressive, and the family had a history of suicide. Avoiding the limelight kept his fragile mental health in check. ‘I used to be a very crazy guy, and I had pain almost every day for years and years and years,’ Bloomfield told biographer Ed Ward in 1973. ‘It never stopped. I don’t know if you’ve ever been crazy or ever really lost your mind to the degree that you hurt every day, physically, man, so that you would do anything to stop it.’

In 1979, Bloomfield entered a mental hospital to come off Placidyl, a hypnotic prescription drug he used to replace heroin. Many close to him believe he was bipolar. ‘Drugs were self-medication’, his friend the writer Larry ‘Ratso’ Sloman said. ‘He wasn’t trying to get high so much as get low.’ Later, he replaced heroin with alcohol.

Three months before he died, Bloomfield came out of retirement to play ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ and ‘The Groom’s Still Waiting at the Altar’ with Dylan at the Fox Warfield Theatre in San Francisco. Dylan was as surprised as anyone that Bloomfield showed up for one last round. Two days earlier, knowing that Bloomfield lived in the neighborhood, he asked singer Maria Muldaur to take him to see him. Aware he was in a bad place, she reluctantly agreed. They found a lucid Bloomfield in his slippers, who was so happy to see Dylan, Muldaur said, that he ‘just threw his arms open and gave him a big hug.’ Dylan tried to persuade him to play one of the Warfield shows; Bloomfield declined. Later, as Dylan went to leave, Bloomfield handed Dylan, who had converted to Christianity, a Bible. ‘This has been in my family at least for a couple of generations,’ he said. ‘It was my grandmother’s and probably her grandmother’s before that.’

Dylan regrets to this day that he could not save Bloomfield. In 2009, when a Rolling Stone interviewer asked if he had ever played with the perfect guitarist, he replied, ‘The guy that I always miss and I think would still be around if he stayed with me, was Mike Bloomfield. He could just flat-out play. He had so much soul.’ In Martin Scorsese’s documentary No Direction Home, Dylan goes even further, calling Bloomfield ‘the best guitarist I ever heard’.

Blues was not a fashion statement or a phase for Bloomfield. It was his everything. And in the end, it was perhaps his undoing. In this he shares something in common with another blues great: Peter Green. Both were Jews with a prowess that drew genuine respect and admiration from not only their peers, but their heroes. Unlike Green, however, Bloomfield is forgotten in the canon of rock greats. Perhaps, in part, because the band that Green led, Fleetwood Mac, went on to sell out stadiums. Had the Butterfield Blues Band gone on to global success, maybe things would be different.

Forty years since his untimely death, few have blazed a trail through the blues like Michael Bloomfield did. At the 2015 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame ceremony, in which he was inducted, a tribute came from an unlikely musical corner: Tom Morello of Rage Against the Machine played Bloomfield’s lines on ‘Born in Chicago’, showing just how widely felt his influence has been.

There aren’t many live videos of Bloomfield, but one that exists on YouTube is of him playing Robert Johnson’s ‘Come On in My Kitchen’, recorded months before his death. The song is a lament of bad luck — a number Bloomfield must have felt in tune with as he battled with his mental health. Gravenites came to believe that Bloomfield was in some way a prisoner of the blues and its mythology.

‘Michael was a young Jewish guy, he was known as a young Jewish guy, and when he was a young guy, he didn’t want to — y’know, his heroes were Elvis Presley, guys like that — goyim, with slicked back hair who had alcohol problems and shit like that. I think by the time Michael finished it all up, there he was, he was drinking wine in the alley, wearing a long coat, looking like the goyim on the street.’

As you watch the magisterial Johnson cover, this strange comment begins to make sense. There he is, a washed-up junkie singing the blues, looking as far removed from his origins as possible. His younger brother, Allen Bloomfield, suspected around the time he died that Michael felt he had played his last, and the rest should be silence: ‘Michael was raring to clock, get loaded, float along and kick back, never doubting the situation… He tied off with a hangman’s noose. Then he overdosed on a drug he never used, detested due to his bipolar illness, and punched out.’

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2021 World edition.