Madonna Louise Veronica Ciccone is embarking on her first greatest-hits tour, but she has forgotten why she was great. In her announcement video for the Celebration Tour, celebrating the fortieth anniversary of Madonna’s self-titled debut, the queen of pop and a random assortment of B-list celebrities — Jack Black, Amy Schumer, Diplo and Meg Stalter, to name a few — reminisced about the queen of pop fellating an Evian bottle in her documentary Truth or Dare. A few days later, Madonna introduced Sam Smith’s and Kim Petras’s striptease at the Grammys. “Are you ready for a little controversy?” Madonna screamed at the crowd, holding a dominatrix cane in the air. The audience was too bored to respond.

In the past few years, Madonna has tried to reclaim her sexuality and her belief that she is solely responsible for hornifying America. She kissed and straddled Drake at Coachella. She straddled Jimmy Fallon’s desk. She straddled a podium at a press conference for the Tidal music app. Like a dog in heat, she has straddled everything in sight lately. More tragically, Madonna — the woman who once refused victim status and sang, “I’m not sorry / I’m not your bitch don’t hang your shit on me” — celebrated the thirtieth anniversary of her Sex book (1992) with an Instagram post decrying the celebrities who fail to credit her art book’s groundbreaking status. “In addition to photos of me naked there were photos of Men kissing Men, Woman kissing Woman and Me kissing everyone,” Madonna wrote. “Now Cardi B can sing about her WAP. Kim Kardashian can grace the cover of any magazine with her naked ass and Miley Cyrus can come in like a wrecking ball.” Madonna has apparently forgotten Mae West’s Pre-Code sex romp I’m No Angel (1933), Marilyn Monroe’s Playboy spread (1953), Linda Lovelace’s mainstream porno Deep Throat (1972), Donna Summer’s Bad Girls (1979), and a zillion other sexual moments in pop culture.

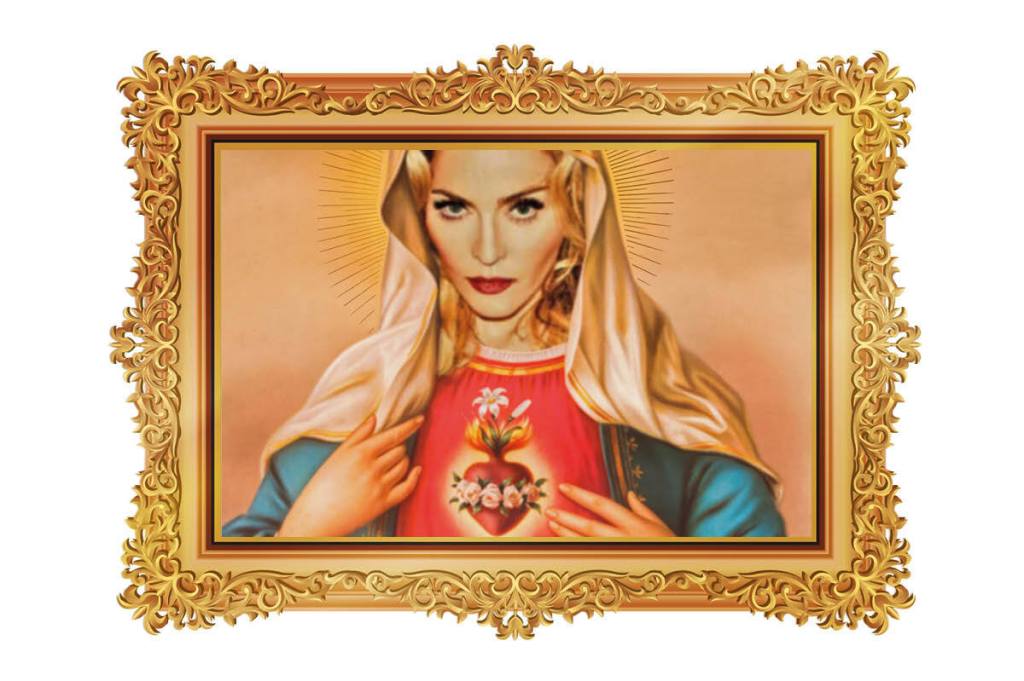

Madonna is so determined to take credit for the sexual revolution, she’s obscured her greatest accomplishment: transforming pop culture into working-class Catholic culture. To Catholic literalists who believe Vatican II was an abomination and think we should go back to Latin mass, it may sound sacrilegious to claim Madonna brought Catholicism to the WASP masses. She confessed via disco songs without penance! She simplified the scripture! She compared her vagina to holy water! She’s goofy! But she is a product the working-class Catholic American community, where Catholicism is a culture as much as an identity — and she transformed that culture into the dominant popular culture.

Born in 1958 into a Catholic Italian-American family in Bay City, Michigan, Madonna entered life as a paradoxical minority. As Harvard professor Jim Cullen writes in Restless in the Promised Land: Catholics and the American Dream, Catholic Americans were a quandary. They followed one of the oldest, most powerful, most corrupt institutions in the West (the Vatican) but lived in a nation founded by Protestants who loathed their church.

Catholicism stifled Madonna. She told New York Times reporter Stephen Holden in 1986, “When you go to Catholic school, you have to wear uniforms, and everything is decided for you… Since you have no choice but to wear your uniform, you go out of your way to do things that are different in order to stand out. All that rebellion carried over when I moved to New York eight years ago to become a dancer.”

And as anyone who attended Catholic school knows, Catholic school gifts students with a paradigm to rebel against while also instructing them in the history of great rebels, like Madonna’s idol Joan of Arc. In a 2019 NPR interview, Madonna described “growing up in the Midwest, not fitting in” and escaping through Catholic artists, like Frida Kahlo and Flannery O’Connor but also the Protestant confessional poet Anne Sexton. “One of the things that I think inspired [Sexton’s] writing, but that she received so much criticism for, was that she revealed too much about herself,” Madonna said. “She was too confessional.”

So, of course, when Madonna began creating music and performance art in the early Eighties, her rebellion still drew on a Catholic aesthetic. Public memory recalls Madonna pumping out manufactured bubblegum pop till her fourth album, Like a Prayer (1989), but even in the visuals for her second album, Like a Virgin (1984), she was recalling Catholic wedding dresses and the Catholic lion motif. Her third album, True Blue (1986), garnered controversy from the left and right for the Catholic anti-abortion lyrics of “Papa Don’t Preach” (“I’m keeping my baby”).

The left believed she was repeating the Church’s anti-abortion rhetoric, while the religious right accused her of promoting teen pregnancy. In the Times profile, Holden identified Madonna’s Catholic upbringing as inspiring everything from “Papa Don’t Preach” to the song “White Heat,” sampling “another mythic rebel, James Cagney,” the Catholic actor who made his name in the 1949 mob flick of the same name. But the most Catholic moment of all came on “Live to Tell,” which functioned lyrically as the adult-contemporary equivalent of a Catholic confession. “I have a tale to tell,” Madonna sings. “Sometimes it gets so hard to hide it well.” She may have simplified confession, but by simplifying Catholicism and wrapping it in pop music tropes, she brought working class Catholic culture into the cultural mainstream.

By the time of her Like a Prayer era, nearly every song referenced religion. Notoriously, Madonna kissed a black Jesus in the “Like a Prayer” video, generating so much controversy Pepsi fired her as their poster girl. The Blonde Ambition Tour went a step further, orchestrating an entire segment set in a church. In case anyone was too dull to grasp that “Oh Father,” a ballad about Madonna’s dad, was also a play on the fathers of the Catholic church, Madonna belted the song while dressed as a priest. The tour’s climax occurred when Madonna fingered herself while singing along to “Like a Virgin” while performing in Rome — a masturbation session that led to the Pope to call it “one of the most satanic shows in the history of humanity.” It was unclear exactly what her sin was. Was the Pope going to excommunicate everyone who had ever masturbated in Rome?

But the most Catholic aspect of her work was actually the confessionals she wrote. “Madonna writes or co-writes most of her material,” writes musicologist Susan McClary. On “Promise to Try,” Madonna sang about her mother dying of cancer when she was five. She set dance beats to testimony about ex-husband Sean Penn abusing her on “Till Death Do Us Part.” Like a Prayer is as confessional as Mary McCarthy’s memoirs, and the confessions were all Madonna’s. Pop music is about distilling a message for the masses, and Madonna was flattening her cultural tradition, like Warhol and his Brillo boxes, and confessing her life story, like many Catholic writers before her.

Religion continued to creep into her most sinful art. In a 1991 Rolling Stone cover promoting the pornographic “Justify My Love” music video and her impending sex-themed album Erotica (1992), Madonna confessed to Carrie Fisher, “Oh, I believe in [the afterlife]. That’s what Catholicism teaches you.” Even Sex featured a nude Madonna hanging over the water with her arms in the air like a crucified Christ. Madonna cannot escape the church.

Midway through her career, Madonna began having children (is there anything more Catholic than hoarding kids?) and trading Catholicism for eastern religions and, later, the Jewish mysticism of Kabbalah. But even in her conversion, she did so in the most working-class Catholic way. At the time she was developing Ray of Light (1998), Madonna watched a Gap Jeans ad that featured the slogan “sky fits heaven so fly it.” As Catholic Americans found religion in their church’s wax statues and Warhol found spirituality at the grocery store and in Hollywood, Madonna took a Gap ad phrase and made it into a spiritual dance song, “Sky Fits Heaven.”

Yet by 2006, the time of her promotional tour for Confessions on a Dance Floor, her contrarian antics matched her Catholicism for the final time. Midway through the show, a video about HIV played. Then “Live To Tell” began playing. A blinking disco crucifix rose from the floor, with Madonna hanging on the cross. It was incendiary, desperate, horny, goofy and very Seventies, but the second Madonna began singing, “I have a tale to tell,” her voice nearly breaking, it was clear that beneath all the sensationalism, she was moved like a nun at church.

As she ages, Madonna acts less and less like a nun, but she sounds more and more like one. When she’s discussing adopting children or getting stern with Cardi B, she’s reminiscent of an elderly sister berating a Catholic school girl.

The most edgy thing an It Girl can do in 2023 is join the church. New York City It Girls once flashed the camera to show their irreverence; now, in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Red Scare host Dasha Nekrasova reverted, and other It Girls joined the Catholic Church. Catholicism has become so mainstream that Baptist Britney Spears complained on Instagram she was shocked to learn she needed to undergo confirmation to hold a wedding in a Catholic church. She thought anyone could stroll into a Catholic cathedral and demand holy matrimony.

It’s unclear how Madonna feels about how Spears, Nekrasova and every other It Girl past and present wants to get confirmed. Last time she spoke about Christ, Madonna tweeted at Pope Francis II. “Hello @Pontifex Francis — I’m a good Catholic. I Swear!” Madonna wrote. “I mean I don’t Swear! It’s been a few decades since my last confession. Would it be possible to meet up one day to discuss some important matters [sic]? I’ve been ex-communicated 3 times. It doesn’t seem fair.” Perhaps, instead of kicking her to the curb a fourth time, Pope Francis should send Madge a thank-you note. She completed Warhol’s mission and turned pop culture into Catholic culture.

This article is taken from The Spectator’s June 2023 World edition.