For anyone who’s a little bit worried about the current state of the Union, Andrew Gimson’s book is a godsend. Donald Trump is often called the 45th president, but he’s actually the 44th — Grover Cleveland, president from 1885- 89 and 1893-97, is counted as the 22nd and the 24th. Among his 43 predecessors, you’ll find plenty of drunks, philanderers and incompetents. Suddenly, the teetotal President doesn’t look so bad after all.

Gimson is a British journalist, but don’t let that put American readers off. He’s worked for the Daily Telegraph and The Spectator and knows politics well. He previously wrote books about the 40 British monarchs since 1066, the 55 British prime ministers since 1721 and a biography of Boris Johnson.

In a healthy sign that Gimson is no hagiographer, Boris tried to pay him the equivalent of the biography’s advance if he promised not to write it and so reveal the racks of skeletons in his closet. Gimson went ahead and wrote it.

This charming, useful book is no hatchet job. Instead, it comes as close as possible to a fair description of the 44 presidents, delivered in plain prose that subtly delivers admiration and condemnation. Just after praising Franklin D. Roosevelt, Gimson quotes H.L. Mencken on FDR: he ‘had every quality that morons esteem in their heroes’. On JFK and Bobby Kennedy, he quotes Harold Macmillan on the first weeks of JFK’s presidency: ‘It’s rather like watching the Borgia brothers take over a respectable north Italian city.’

It’s telling that you can’t say whether Gimson is a natural Republican or Democrat. When it comes to British politics, he is, incidentally, a Conservative, but his wife, Sally, is a Labour party activist, prevented from standing as an MP by the extreme left in Jeremy Corbyn’s party.

You can only stand back in amazement at the Founding Fathers — and the astonishing robustness of the American political system — when you consider the mixed bag of presidents that followed. Yes, the Founding Fathers’ story has been told a million times, but Gimson retells it briefly and well. As he writes, George Washington ‘was not a king but was taking the place of a king, and the reverence with which he was regarded had to be kept in bounds’. The second president, John Adams, even proposed that Washington be called ‘His Majesty the President’.

That reverence isn’t surprising. Presidents have astonishing power — much more than the British queen and prime minister combined. It’s surprising then that, with all that power and reverence, so many presidents are forgotten today: ‘Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, the current President and perhaps half a dozen others, most of them within living memory, take almost all the light.’

Gimson has to tell the old familiar stories: Washington cutting down his father’s cherry tree; Abraham Lincoln calling on ‘the better angels of our nature’ in his first Inaugural Address.

But Gimson also drops in some unfamiliar ones — Jefferson dropping the custom of bowing to visitors and adopting the more democratic idea of shaking hands, for example. And Gimson is fully aware of the problems of the Founding Fathers — not least their slaveholding — while not trying to topple their statues.

There’s a serendipitous aspect to a chronological study. You get a feel for the changing attitudes in early America. James Monroe, President from 1817-25, was the first president to tour New England — something early Virginian presidents hadn’t bothered to do because, from their point of view, it was hostile territory. You also get a feel for the gathering tides in American history. Long before Lincoln comes to the White House, the slavery question is rising to the top of the presidential inbox.

The great presidents are given more attention by Gimson — none greater than Lincoln. Gimson is alive to Lincoln’s ambivalence on race, quoting his words, ‘I do not understand that because I do not want a negro woman for a slave I must necessarily want her for a wife.’ But Gimson is also alive to Lincoln’s gift for ‘choosing the time and place to fight, making his opponents look disreputable and incoherent, and allowing them to impale themselves on their own contradictions’.

Readers who, like me, have low, gossipy interests will be pleased with the presidential peccadilloes on show, too. Give me a naughty president rather than dull Rutherford B. Hayes (president from 1877-81), who kept a dry White House. As his Secretary of State, William M. Evarts, declared of one presidential banquet, ‘It was a brilliant affair; the water flowed like Champagne.’

Not surprisingly, the most powerful man in the world often had a powerful sex drive. John Tyler (president from 1841-45) married for the second time, at 54, a wife 30 years his junior and had seven children. Tyler, born in 1790, has a living grandson. The family still lives at Tyler’s Virginia farm, which the president called Sherwood Forest because, like Robin Hood, he was an outlaw — in Tyler’s case, from the Whig party.

There’s nothing like a good presidential sex scandal, even if it isn’t the president himself having the sex. Andrew Jackson (president from 1829 to 1837) took a noble stand in defense of ‘Pothouse Peg’, a tavern-keeper’s notorious daughter in Washington, DC. When Sen. John Eaton asked Jackson whether he should marry her, after her first husband killed himself, Jackson said he must if he loved her. The muckrakers piled in, saying, ‘Eaton has just married his mistress, and the mistress of eleven dozen others.’ And Henry Clay declared of Pothouse Peg, ‘Age cannot wither nor time stale her infinite virginity.’

The most enjoyable sex scandal before Bill Clinton involved Grover Cleveland, who, as a bachelor, had a child by a widow. Republicans taunted Cleveland by chanting, ‘Ma! Ma! Where’s my pa?’

When Cleveland became president, his supporters cried, ‘Ma! Ma! Where’s my pa? Gone to the White House. Ha, ha, ha!’

In a foreshadowing of the Clinton scandal, Warren G. Harding (president from 1921 to 1923) conceived a child by his mistress in a White House closet. As she put it, ‘In the darkness of a space not more than five feet square, the President of the United States and his adoring sweetheart made love.’

The difference between then and now is that scandals were then swept under the carpet and presidents remained married — Ronald Reagan was the first divorced president to enter the White House in 1981.

A presidential tour d’horizon also shows how vulnerable presidents are. Four have been assassinated — Lincoln, James Garfield, William McKinley and Kennedy. That’s almost one in 10 — not very reassuring if you’re a Secret Service agent.

All sorts of other terrible accidents and illnesses befall presidents. Zachary Taylor, president from only 1849 to 1850, died after officiating for hours under a boiling sun over the laying of the foundation stone for the Washington Monument. He tried to keep the heat at bay with iced water and cherries in iced milk, but they couldn’t save him.

William Henry Harrison was president for only a month in 1841 before being killed by the pneumonia he caught giving his inaugural address in bitter cold. The address — at 8,445 words — was much the longest ever given: a lesson to all speechifiers.

Joe Biden will take heart at how many presidents were once vice presidents — 13 in all. But, as someone who lost his wife and daughter in a 1972 car crash, Biden will know, too, that the great and the good aren’t spared family agony.

Franklin Pierce (president from 1853- 57) watched in anguish when, just before his inauguration, his son’s brains were dashed out in a train crash in full view of his horrified parents. The Lincolns lost their son Willie when he was only 11.

All these tragedies show that, surprising as it may seem, presidents also happen to be humans. And, like Donald Trump, plenty of presidents have been surprisingly insecure, too. James Polk (president from 1845-49) was so short and had so little presence that his wife encouraged the playing of ‘Hail to the Chief’ to signal his arrival. This had been done before but, under Polk, it became the custom.

If you think Trump is a trust-fund kid, consider the really posh presidents: Teddy Roosevelt, say, one of the seventh generation of his family to enter the world on Manhattan Island — his ancestor Claes Martenszen van Rosenvelt emigrated in 1649 from Holland to New Amsterdam before it was New York. Franklin Delano Roosevelt was Teddy’s fifth cousin, born from the same blue-blooded stock.

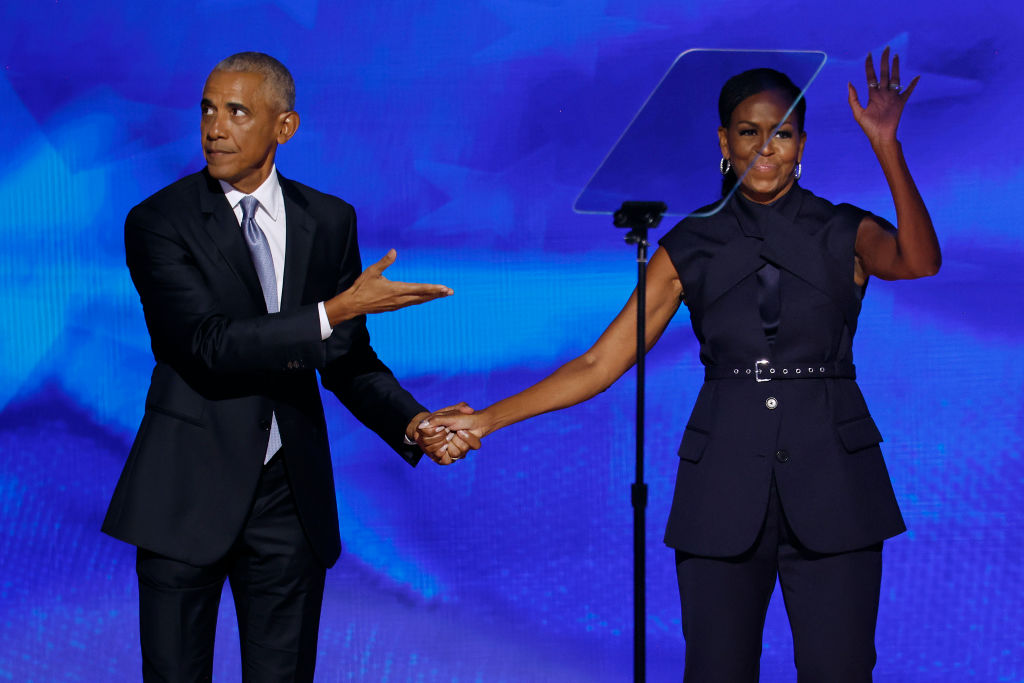

Gimson’s sketches of the post-war presidents are necessarily less remarkable, because anyone interested in politics is pretty familiar with their lives. Gimson praises Barack Obama for his exceptional manners and brilliant oratory, but acknowledges his presidency’s faint but unmistakable sense of anticlimax.

In the end, everything fades compared with the orange elephant in the room. Trump may be barbarous, Gimson says, but, in many ways, he’s no worse than some of his predecessors. Remember the licentiousness of JFK, the Vietnam horrors under LBJ, Nixon’s lies, Clinton’s morals and George W. Bush’s Iraq disasters.

With no disrespect to the mighty office, it’s hard not to agree with James Bryce in an 1888 book, Why Great Men are Not Chosen President. Bryce wondered why ‘this great office is not more frequently filled by great and striking men’.

This article is in The Spectator’s November 2020 US edition.