To be a good illustrator, said Mervyn Peake, it is necessary to do two things. The first is to subordinate yourself entirely to the book. The second is ‘to slide into another man’s soul’.

In 1933, at the age of 22, Peake did precisely that. Relinquishing his studies at the Royal Academy Schools to move to Sark in the Channel Islands, he co-founded an artists’ colony and took to sketching fishermen and romantic, ripple-lapped coves. He put a gold hoop in his right ear, a red-lined cape over his shoulders, and grew his hair long, like Israel Hands or Long John Silver.

The incredible thing was that he had yet to receive his commission to illustrate Treasure Island. By the time the job came through, in the late 1940s, he had been sliding into more piratical souls for more than 20 years. Peake, by all accounts a gentle man, is probably best known today as the creator of Titus Groan and the dastardly Steerpike in his brilliant Gormenghast trilogy. He was also, however, an adroit and often unsettling draughtsman, producing the most brooding and memorable illustrations for Treasure Island and Lewis Carroll’s Alice books of the 20th century.

‘He drew all the time,’ recalls his son Fabian, a talented artist and poet in his own right. ‘He was an all-round artist, but often thought of himself as a painter.’

Last year, the British Library acquired his visual archive — 17 boxes containing more than 300 of his illustrations, preparatory drawings and framed works spanning the period from 1918, when he was seven years old, to 1962 — for a sum of half a million pounds. Among the papers are some of his earliest schoolboy sketches for the text of Treasure Island.

Growing up in China (he was born at Kuling in 1911), where his parents worked as medical missionaries, Peake learned the book by heart and depicted the pirates in watercolor dashing across the island. When he later came to write his own books, he would reverse this process, drawing his characters first in order to describe them.

‘Peake was synesthetic,’ explains Rachel Foss, curator of the new archive. ‘The act of drawing was often part of his literary process… It’s impossible to separate his art from his writing.’

Peake’s pictures, which join the Peake literary archive acquired by the library a decade ago, are currently being catalogued so that visitors can view them from 2022. What emerges most clearly from this collection is how far islands and sea travel inspired Peake throughout his life. From his final drawings for Treasure Island to his darkly atmospheric series for ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’, he was forever striving to capture the changing nature of coastlines.

Often, he balanced his islands on waves, as if they were mere spumes. In ‘Floating Islands’, one of the earlier drawings in the archive, settlements rest precariously on huge, white, Hokusai-like crests. One thinks of the Bellman ‘Supporting each man on the top of the tide/ By a finger entwined in his hair’ in Lewis Carroll’s ‘The Hunting of the Snark’, a poem Peake illustrated in 1941. The image (a pun on his name?) recurs in Captain Slaughterboard Drops Anchor, Peake’s picture book of 1939, where the pipe-smoking pirate with a gappy grin and rings in his ears sails up the peak of an enormous wave to reach a mysterious island.

Like his best characters, Peake’s islands perturb while they entice. No sooner do Slaughterboard and his crew make landfall than they happen upon carnivorous looking plants and a peculiar Yellow Creature ‘as bright as butter’. Slaughterboard, tired of marauding, takes the creature aboard his ship, before deciding that he would prefer a leisurely island life in its company. The island and creature are depicted with a yellow wash. The other characters — even the purple monsters — are done in black pen and ink alone.

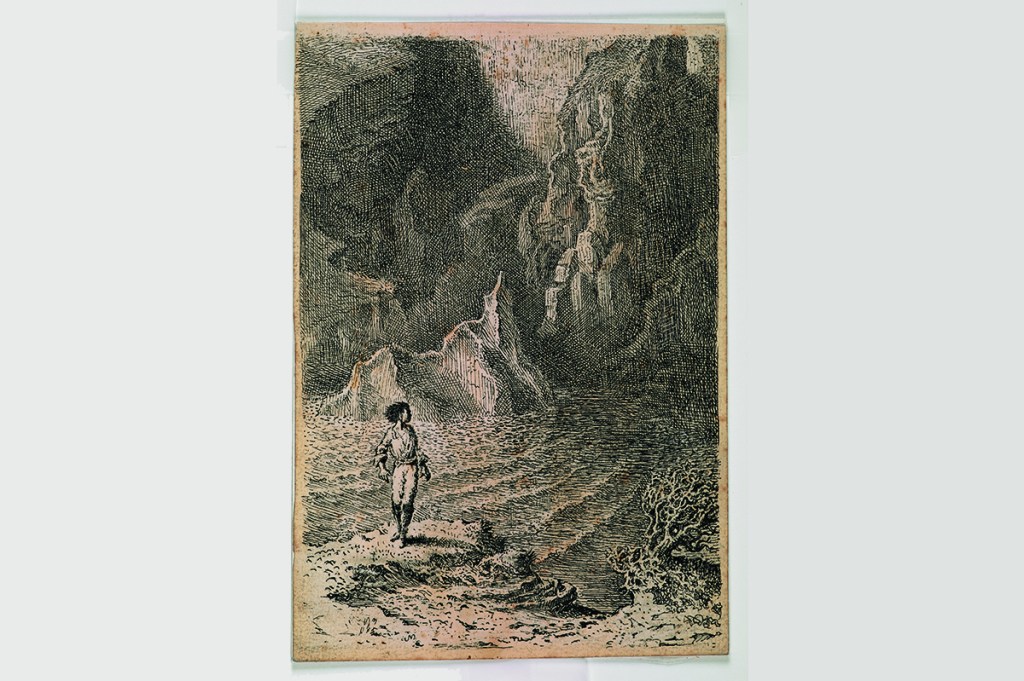

The Snark — a slow-witted being with a flavor ‘meager and hollow, but crisp’— inhabits another faraway island. Here, towers of rock, seemingly hewn by hand, envelop the motley crew — Billiard Marker, bewigged Barrister, Beaver — in sinister shadow.

Remote Gormenghast, inspired perhaps in part by Arundel Castle and the walled cities of China, resembles ‘an island of maroons set in desolate water beyond all trade routes’.

In the mid-1930s, Peake temporarily gave up his own island life for London, where he met his wife, the artist Maeve Gilmore, while teaching life drawing at Westminster School of Art. With the coming of war, he was commissioned to paint glass-blowers in Smethwick. His drawings of puff-cheeked craftsmen and oil paintings of workers juggling their wares in a ‘ballet of glass’ are exquisite. He ended his war drawing the last of the prisoners at Bergen-Belsen — the most harrowing commission imaginable.

Peake’s return to Sark with his wife and young family in 1946 was very much an act of escapism. ‘The island represented the romantic ideal,’ says Fabian. ‘My parents were young artists who wanted to do something exciting with their lives.’ Living in a large but rundown house called Le Chalet, Mervyn Peake began work on Gormenghast.

Preparatory drawings for the characters clearly reveal the influence of Goya and Dürer as well as Rowlandson and Blake. Steerpike, his eyes ‘close-set and the color of dried blood’, has the skinniest of faces, with shifty eyes and a tight mouth. Looking at his portrait, it is little wonder that Titus, Earl of Groan, is so desperate to escape his birthright in the books.

Peake, by contrast, seldom felt claustrophobic on Sark. He described the diminutive island as a ‘strange, wasp-waisted ship of stone’, suggesting that he saw it less as a destination than as a vessel suspended in time. Indeed, by the time he came to write of the island’s moonlit rock running down to the shadows of the sea in Mr Pye, his novel of 1953, he had returned to London.

While his work won many admirers in his lifetime, including Anthony Burgess and Elizabeth Bowen, Peake never felt that he had arrived. He struggled financially, taking just £5 for ‘The Hunting of the Snark’ and, on the bad advice of Graham Greene, a one off payment of £10 for designing the logo for Pan Books when he might have earned royalties on every book printed. By 1957, he had pinned his last hopes on a play, The Wit to Woo, only to receive catastrophic reviews.

Peake’s ensuing breakdown may well have marked the onset of his battle with Parkinson’s and a related form of dementia. Over the coming months and years, he found himself ostracized, as former friends and editors shamefully turned their backs on him. The fanciful rumor that he had driven himself mad through his pictures and stories found a certain currency. ‘All that darkness, dear, gets to you in the end,’ said Quentin Crisp.

Peake, still only in his fifties, endured electric shock therapy to treat his illness, so little understood at the time, with disastrous results. In the end he was institutionalized. It was then that his work really began to take off.

Peake had been planning a spin-off to his Gormenghast books when he became unwell. In Titus Awakes, completed by his widow, the hero leaves Gormenghast and finds work in an institution, where he encounters an artist who is losing his ability to walk and draw.

He sees the artist discharged after a misdiagnosis and goes after him until he reaches an unnamed yet familiar island. Sark, the ship of stone, was summoning its kindly pirate on his final voyage.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2021 US edition.