The climactic scene in the Italian director Paolo Sorrentino’s latest film, The Hand of God, finds the teenaged Sorrentino stand-in, Fabietto, being verbally attacked by an aging director named Capuano, the seaside at their backs. At this point in the film, the young Fabietto (Filippo Scotti), a sullen mama’s boy searching for meaning, has suffered an immense tragedy and is looking for answers. Enter the wise man.

The scene, like many in The Hand of God, is on the nose and borders on the melodramatic, but when Capuano (Ciro Capano) yells “how does this city not inspire you?” at Fabietto, he reveals the film’s emotional core. The Hand of God, like Sorrentino’s previous work, is highly stylized and aesthetically beautiful — a true visual feast. But if films like The Great Beauty and This Must Be the Place were detached and clinical, the opposite is the case here: The Hand of God transcends aestheticism and levels you with its beautifully emotional story of life, loss and, most importantly, coming of age.

The Hand of God takes place in Naples during the early 1980s, and from the opening scene — a long and languid shot of the coast — it’s clear that Sorrentino finds inspiration in the city and its denizens. The magic of Naples is lost on Fabietto, but Sorrentino, perhaps remedying his own youthful folly, presents the city as a working-class haven, where cigarette smugglers, soccer obsessives, and beautiful women of all shapes and sizes attack the day with an electrifying vigor. Naples is alive, but Fabietto, dulled and lifeless, fails to see the epiphanic life-altering moments he so desires. The tension in The Hand of God, a film that relies not on plot machinations but on atmospherics and aesthetics, hinges on a simple question: will Fabietto, after the tragedy that befalls him, accept the mystery of life?

In interviews leading up to the film’s opening, Sorrentino was open about The Hand of God’s autobiographical nature. The great tragedy of Sorrentino’s life, just like Fabietto’s, was the loss of his parents in a freak accident. One of the film’s marvels is how Sorrentino, through his proxy Fabietto, constructs a cinematic philosophy that his younger self seemingly took for granted. The key to filmmaking, Sorrentino seems to be telling Fabietto, is that of muse and melancholy. You must find your muses, embrace the melancholy in life, and be discerning enough to know that sometimes the greatest muse of all is the very melancholy that nearly destroys you. It can take a long time to learn this lesson, and even longer to have it shape your artistic impulses, which is why Sorrentino, middle-aged and critically acclaimed, created The Hand of God at this juncture in his career.

The film has a rare emotional breadth because Sorrentino’s dueling muses battle for supremacy while he exquisitely paints the coming-of-age picture.The most obvious of these muses is the female form. Fabietto is obsessed with his maternal aunt, the voluptuous and mentally unstable Patrizia (Luisa Ranieri), who disrobes in public whenever she pleases. Some of the film’s more memorable scenes take place in an Italian beach house, where Fabietto’s extended family comes together and the wonderful women of the clan put on a show. Fabietto’s mother, Maria (Teresa Saponangelo), juggles fruit and hogs the limelight, while another aunt, overweight and utterly charming, parades around her geriatric fiancé.

The great pleasure in these slice-of-life moments comes from Sorrentino’s ability to juxtapose the beautiful and the grotesque in such an alchemic manner that all the traditional standards of beauty are tossed out the window. Fabietto, disgusted and aroused, soaks it all in — his budding filmmaking sensibility taking shape, even if he doesn’t know it.

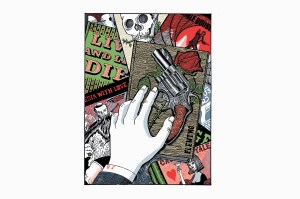

The flipside to Sorrentino’s female adoration is his infatuation with the Argentine soccer great Diego Maradona, whose specter floats at the periphery of the film. Fabietto’s fixation on Maradona reminds us of the male muses, often forgotten, who also form young men and push them to adulthood. Maradona’s famous goal known as “the hand of God” — in which he slyly punched a ball with his hand into the net in the 1986 World Cup — inspired the film’s title, and the athlete is present in one of the film’s most important scenes, in which Fabietto and his brother watch him achieve seemingly impossible feats during an open practice session.

“Perseverance,” the brother says: “that’s what Diego has.” In the film’s crucial scene, Capuano, the wise director who represents this masculine doggedness turned to art, challenges Fabietto on his commitment to filmmaking. Fabietto reveals the source of his pain, and Capuano, pleased, strips and dives into the ocean. He knows that Fabietto the filmmaker has finally been born.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2022 World edition.