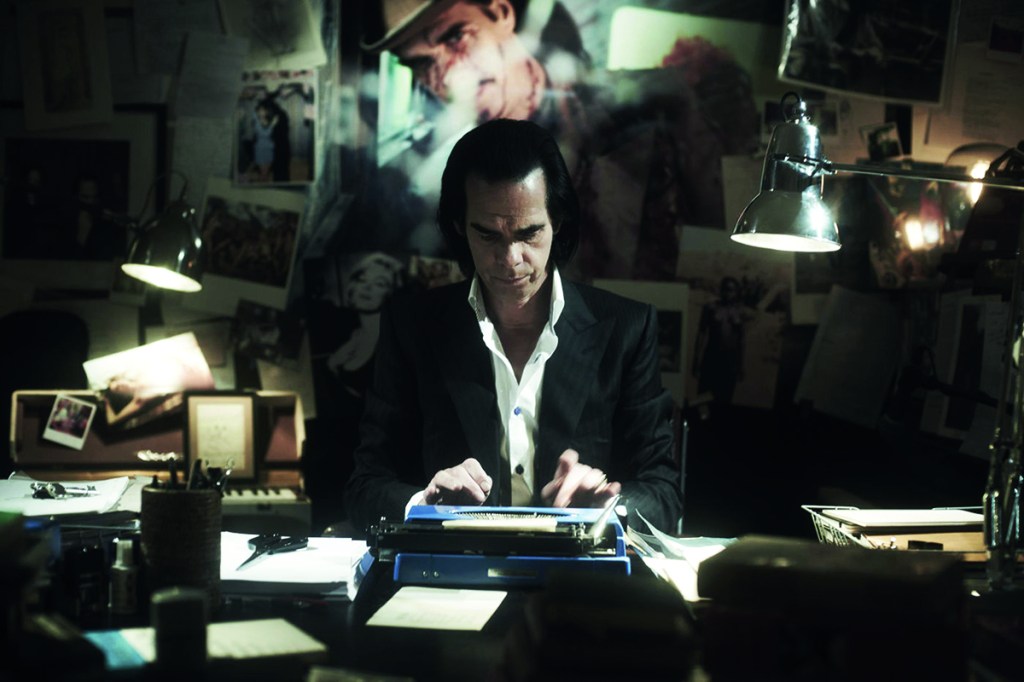

The musician, novelist and occasional ceramicist Nick Cave is the most literate of that often-decried breed, the rock star. Over the course of a forty-year career that began with the raucous punk act the Birthday Party and continues to this day with the Bad Seeds, in addition to eclectic solo and film-scoring work, he is restlessly innovative. Not only has he written countless lyrics that approach Dylan or Cohen-esque levels of profundity, but he has written film screenplays, novels and even a loose collection of musings about life on tour, The Sick Bag Song.

Yet he shows no interest in writing the autobiography that many might have expected from him. In Faith, Hope and Carnage, a series of wide-ranging and in-depth conversations between Cave and his long-standing friend, the journalist Seán O’Hagan, he is explicit about his distaste for biography of any kinds, saying “I find my own story, my own history, unbearable, mostly — at least the one that is constantly trotted out. Not that I feel ashamed of it; rather, I find it wearying, exhausting. I don’t like biography as a form, really. I don’t tend to read it.”

Therefore, it is this book that is likely to be the closest that Cave’s millions of admirers ever come to a candid account of his life, told through long, often soul-baring detail. Some might be surprised that a figure who has traded on mystery and persona throughout his career has now, in his sixties, become so transparent about himself. Yet, in truth, this has been a process that Cave has been exploring for many years, with his “Red Right Hand Files” — where he regularly answers questions that his admirers send to him with a mixture of humor and candor — and even a series of events, “Conversations with Nick Cave,” where he took to the stage and allowed audience members to ask him anything that they pleased. These were largely litanies of praise for the musician, although I have to applaud the humorist who stood up at one event in Brighton, England, and said “Nick, I live in your old apartment. Where’s the water valve?” Cave was, by all accounts, most amused.

There is a reason for this accessibility and almost fervent desire on Cave’s part to speak his mind. In July 2015, his fifteen-year old son Arthur took LSD and had a fatal accident after falling off a cliff, not far from his family home in Brighton. It was a traumatic occasion for Cave and his wife, the fashion designer Susie Bick, but it also sparked a new phase in his career, producing remarkable albums such as 2016’s Skeleton Tree, 2019’s Ghosteen and his lockdown-recorded collaboration with Warren Ellis, Carnage, as well as giving him the impetus to become a different kind of public figure. He eschews interviews with journalists, preferring to communicate directly with his admirers, whom he adores; he announces here that “as far as the fans were concerned, yes. They saved my life. It was never in any way an imposition. It was truly amazing. And what you remember ultimately are the acts of kindness.”

As the title might suggest, there are three dominant themes throughout Faith, Hope and Carnage, and one of them is the loss of his son. Arthur is a persistent presence throughout the book, first appearing on the fourth page, when Cave says “Arthur died and everything changed. That sense of disruption, of a disrupted life, infused everything… it is difficult for me to go back there, but it is also important to talk about it at some point, because the loss of my son defines me.” He talks of his boy with great affection, even reverence, but also discusses the effect that his death has had on his life and art, saying “The loss of my son is a condition, not a theme. It’s a condition and, as such, it infuses everything. My relationship to words has changed, for sure, but so has my relationship to all things.”

Yet despite Cave’s brutal candor — there is an account of his discovering his son’s death and viewing his body that is heartbreaking to read, and must have been utterly devastating to recall, and to share in this kind of book — there are still moments of recalcitrance. At one point, O’Hagan encourages him to discuss his son less as a symbol and more as a human being, and the ever-articulate Cave is flummoxed, saying “Oh God, Seán. I don’t know. He was such a great little kid… I’m sorry… I can talk about Arthur in some ways, and other ways, I just can’t go there.” The reader is aware of a barrier being politely but firmly erected; some matters are too personal to be shared.

This does not hold true for Cave’s social and religious beliefs, which are discussed freely and openly. He talks of his fascination with both the trappings and liturgical convictions of religion — which have informed his music and lyrics all of his career — and speaks freely about his unconventional views of Jesus and spirituality, saying “Religion is spirituality with rigor, I guess, and, yes, it makes demands on us. For me, it involves some wrestling with the idea of faith — that seam of doubt that runs through most credible religions. It’s that struggle with the notion of the divine that is at the heart of my creativity.” Cave’s god is not necessarily that of the Biblical tradition, but something else altogether. As he says, “sometimes it feels to me as if the existence of God is a detail, or a technicality, so unbelievably rich are the benefits of a devotional life.”

It comes as little surprise to find, given Cave’s attitudes towards spirituality and the ordered life of both the person and the soul that he craves, that he self-defines as a conservative, saying “that’s always been the case, and not just in terms of my faith. I think temperamentally I’m conservative.” He has been unafraid to call out the unquestioningly pro-Palestinian views of some of his peers, most notably Roger Waters, and he has trenchant comments about the horrors of cancel culture, of which he says “I don’t think anyone can question the stifling and deadening effect of the fear of cancellation — or even just getting it wrong — on art, writing, public discourse and even comedy. It has made the world of ideas so relentlessly uninteresting.”

For a man who, by his own admission, spent much of the Eighties and Nineties in a miasma of heroin addiction, he is admirably clear-sighted about the greater hypocrisies of our age. He describes woke culture as

akin to a fundamentalist religious impulse… it may reflect an unconscious desire to return to a non-secular society” and talks angrily of “the performative aspect to the theater of cancel culture that is essentially vindictive… it’s as if autocratic ideas of virtue and sin have come into play, and, as a result, prohibitions and punishments have been put in place, enforced by a kind of moral callousness that, in my view, is akin to the very worst aspects of religion — the fundamentalist, joyless, sanctimonious aspects that have nothing to do with mercy. Cancellation is a particularly ugly part of its weaponry and can end up as a kind of sadism dressed up as virtue.

This may offend the left, but Cave is far beyond caring. He has a greater truth to tell.

Faith, Hope and Carnage features some unexpected detours. There is a paean of praise to Coldplay’s Chris Martin; an unlikely friend for Cave to have, perhaps; he is described as “a very funny guy, with a perverse sense of humor [and] also disarmingly forthright. He tells his truth, as he sees it, as a matter of principle. He’s tough and isn’t afraid to speak his mind.” Cave describes writing “Into My Arms” — perhaps his finest love song, a perfect marriage of the sacred and profane — in a rehab dormitory, sitting on a bunk bed. He names Elvis as his favorite singer. And he talks with enthusiasm about his newfound love of pottery and ceramics, something that I had assumed to be a joke, but which has turned out to be a remarkably sustained pastime. True to form, the first set of pottery that he produced features Satan as its pivotal character.

This may ultimately be a book for Cave aficionados rather than the general reader, but it’s remarkably literate, humorous and, by the end, deeply affecting. O’Hagan is a skillful interlocutor, asking penetrating questions and seldom inserting himself into the narrative, but it’s his subject — rightly — who dominates the conversations, speaking with a rich degree of insight into everything from his junkie youth to his distaste for “morally obvious” contemporary fiction. And at the end, there is something life-affirming about the way in which Cave has absorbed every parent’s nightmare and, without recovering from or attempting to belittle the trauma, shaped it into something vitally important for his creative soul.

You end the book feeling that you know its subject intimately, and you wish him well. As Cave himself says, “hope is optimism with a broken heart.” The deeply affected can only agree with his hard-won wisdom.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2022 World edition.