Unpopular opinion: film noir is dull, self-indulgent and grossly overrated. I recognize it has given us some great performances — Bogart, Peter Lorre and Sydney Greenstreet in The Maltese Falcon, say — as well as chiaroscuro lighting, laconic dialogue, cynical hard-bittenness and cancerously heroic quantities of smoking. But that’s exactly the problem. Film noir is so in love with its look and style, the plotting comes a very poor sixth.

What, though, does any of this have to do with Perry Mason, the suave, brilliant, clean-cut lawyer played by Raymond Burr in the long-running Fifties and Sixties courtroom drama series? Well, bizarrely, HBO has decided to revive him for another of those dark and grimy origin stories that Joker made so fashionable.

Though I, like almost everyone alive, am far too young to remember the original Perry Mason, I can smell the stench of pervy gratuitousness a mile off. It’s like discovering that the young Doctor House was addicted to crystal meth and voodoo cat sacrifice, or that Frasier and Niles Crane were the silent partners of Jeffrey Dahmer, or that Principal Skinner from The Simpsons was an imposter called Armin Tamzarian who replaced the real Seymour Skinner, his Green Beret platoon sergeant, after he went MIA in ’Nam.

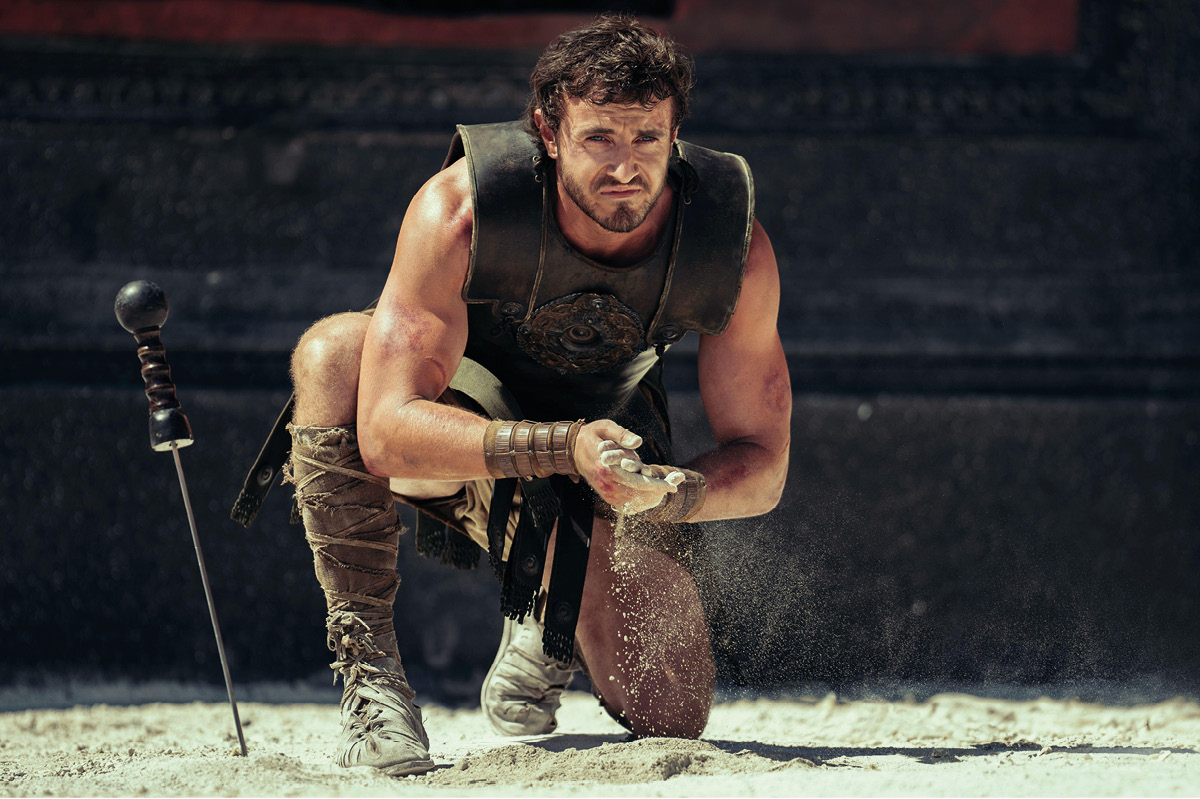

All right, so the last one did actually happen. But at least The Simpsons has the excuse of being funny and random and digressive. The new Perry Mason is a backstory set in Thirties California. Matthew Rhys plays him as a slightly soiled and sordid deadbeat in a greasy jacket, forever whipping his period camera out even at the most inappropriate moments, forever smoking his cigarette in that special cup-handed way which bespeaks the hinterland of character motivation. Private Perry served as a doughboy in the Meuse-Argonne offensive of World War One, a bloody fight lavishly recreated in later episodes. This scarred him in unimaginable ways, creating the tortured smoker we now see before us.

My guess is that the makers of this reboot saw Babylon Berlin (with its morphine-addicted cop, its trench-warfare flashbacks, its violence and corrupt Thirties politics, its rank sexual perversion) and thought, ‘Let’s have some of that!’ But Weimar Berlin has the advantage of cabaret and Nazis, whereas Thirties LA is mostly just fedoras, corruption and post-Depression squalor, relieved only by a light sprinkle of tarnished Hollywood fairy dust and a bit of strange but true contemporary detail, like the evangelical movement that swept California in that decade. It’s so bleak you wonder why everyone didn’t just walk into the Pacific and get it over with.

That’s certainly how I felt for most of the first episode. The period authenticity is so authentic it’s distracting. You keep noticing how authentic it is: the cars, the period camera, the lettering on the billboards. But to what end?

At the beginning, a horrible murder is committed: a kidnapped toddler, supposed to be exchanged for a ransom payment, is returned to his parents dead, with his eyes stitched open like some macabre clown mannequin. You just know, though, that, this being film noir, you’re never going to get a satisfactory answer about whodunit or why they dunit. The murder is just the MacGuffin that provides a flimsy excuse for a frustrating, Lost-style meander through the murk, ambiguity and decay of Thirties Hollywood. It’s Chinatown, Jake, only without the solace of Jack Nicholson and Faye Dunaway.

[special_offer]

To lighten the mood a bit you’ve got lovely John Lithgow as Mason’s mentor attorney, E.B. Jonathan, and Juliet Rylance as his future legal secretary Della Street. Occasionally, too, there’s a joke, like when Mason is asked why he doesn’t find the slapstick in a Laurel and Hardy film funny. ‘A fucking horse kicked him in the ass, how do you not find that hilarious?,’ his partner asks.

‘I grew up on a farm,’ Mason replies.

Cut to Mason on his farm, and it is indeed miserable. He has a ripe, mature and voracious Hispanic girlfriend with whom he has energetic if chaotic sex which they obviously both enjoy but, of course, this being a 2020 take on the 1930s, his Latinx lover is far too liberated and independent and powerful to do anything so demeaning as to bring him a tequila after sex.

Reviews have commented on the ultrarealism of Perry Mason’s violence. This doesn’t remotely surprise me. All cultures, past or present, ramp up the morbidity and perversion in their decadent phase. There’s precious little light and joy here, and it’s no consolation to know that when he grows up, Perry Mason becomes a successful attorney who puts away lots of bad guys and saves lots of innocent ones. My view is that if this is how grim his past was, it would have been better left a mystery