The preservation of a strict social hierarchy rests very often on the enforcement of correct modes of address. In America today any university student may address any other as “dude,” but those who have attained a certain level of prestige will object if an unwary low-status blunderer ventures to call them “bro.” Rebels seeking to overturn rigid class systems will often start by violating such regulations.

The German revolutionaries of 1968, for example, made a point of addressing everyone as arschloch, or “arsehole” — a radical usage I remember being startled by it in mid-1990s Kreuzberg bars until it was explained to me that I wasn’t being insulted. Their other move, to use the intimate du, rather than the formal Sie, for “you,” has taken much stronger hold. In 1793, the French revolutionary government issued a decree forbidding the use of vous, only for Napoleon to overturn it. In seventeenth-century Britain, Quakers addressed everybody by their first names and used the personal pronoun “thou.” We are told in Keith Thomas’s superb In Pursuit of Civility that one brave soul even called the magnificently daunting Duke of Newcastle “Phil.”

One of the earliest examples of this interesting phenomenon can be seen in the German Peasants’ War, or Bauernkrieg, of 1524-25. This was a sequence of uprisings by the disenfranchised and heavily burdened lower classes but also included quite affluent people whose freedom of action, economic activity and movement was still being heavily restricted. It was given impetus by the tide of the Reformation started by Martin Luther. The rebels’ demands for political and economic change were mixed with theological assertions. But one of the things that united them was the wish to be able to address everyone as du.

In some ways, this quest for informality is the most persistent legacy of historical revolutionary moments. In Britain today there can be very few people who expect to be addressed formally, and the shift in behavior is a fundamental one. Other changes demanded by great attempts at revolution appear incomprehensible in their theological distinction-making — or arbitrary, such as the French Revolution’s introduction of the decimal day, consisting of ten hours of 100 minutes each. The question of who you’re allowed to say “you” to, however, is a constant theme.

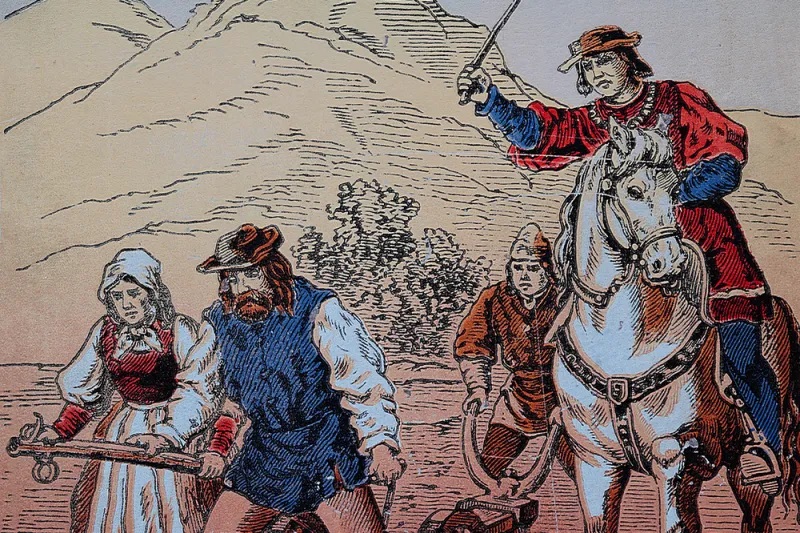

Some knights, such as Götz von Berlichingen with his iron false hand, changed sides and joined the peasants

The Peasants’ War is an extremely challenging episode for modern readers to understand. The insurgents across Europe lived under different regimes and had different objectives. Most were probably illiterate. (Lyndal Roper provides no estimate of what proportion of the population could read, or of how many of the literate even could afford paper and ink, though historians have been able to give reliable figures for literacy in other periods without official records.) Different demands were made of the nobility in different places. Some knights, such as the celebrated Götz von Berlichingen with his iron false hand, changed sides and commanded peasant troops.

A few demands circulated, including the revolutionary Twelve Articles presented to the Swabian League, which are sometimes seen as the first draft of civil liberties legislation in continental Europe. (They come some centuries after Magna Carta, of course, and in any case, they had no effect.) Many of the communities engaged in the uprising based their demands on scriptural precedent, and the Reformation preacher Thomas Müntzer came close to becoming the rebel leader. But Luther — who must have been the inspiration for many — fiercely opposed the revolt. The Reformation could scarcely have proceeded had he taken the peasants’ side against the princes. He would have been executed — as Müntzer was.

It is hard to discern anything resembling a strategy in the peasants’ actions. Large gangs roamed the countryside and succeeded in ransacking the monasteries, which were soft targets. If they thought freedom from serfdom would follow with similar ease, they were sadly deluded. In many ways it suited the great princes if the power and splendor of the monasteries were destroyed by lawless gangs. After the war, most of the monks’ wealth passed into the hands of the nobility.

When it came to confrontation with anything resembling a professional military operation, the peasants, of course, were slaughtered. Before one battle, a Reformation preacher assured his followers that the League’s cannon would turn around by a special providence of God and shoot their own men.” Once the rebels were defeated, leaving perhaps a third of them dead, the princes imposed a state of affairs which made ordinary lives much harsher than they had been before. If the story of this war is unfamiliar to most of us, it may be because it is not only immensely complex, but it resolved absolutely nothing.

The peasants’ demands would have had little chance of succeeding since they were rooted in community responsibility and strong control, not personal liberty. Another class of hereditary apparatchiks would simply have been created, exercising brutal authority. For this reason, the revolt occupies a significant place in Marxist wishful theology. Engels wrote a book about it, and it loomed large in the official DDR interpretation of history. Between 1976 and 1987, the East German painter Werner Tübke created a colossal, mad panorama, winningly titled “Early Bourgeois Revolution in Germany,” which you are welcome to visit in Bad Frankenhausen. Effective liberty would only come with the opportunities of capitalism, individual freedom and social mobility, not with declarations of theological duty to be imposed by new authorities. But for Roper “capitalism” and “serfdom” are equally distasteful terms.

Despite its ringing title, I don’t think Summer of Fire and Blood is for the general reader. It is quite difficult to follow the sequence of events, but it would have helped greatly had the author tried to evoke them more imaginatively. When we are told that a force “seized” a town, it is hard to visualize what actually took place — what weapons were used, or indeed what the town might have looked like. Several castles are said to have been “burnt to the ground.” Were they made of stone, or wood, or what? Some important centers of the Reformation — Wittenberg, Leipheim, Eisenach and delightful Schmalkalden — are now quiet backwaters, unfamiliar to most visitors to Germany. (The woman in the tourist office in Schmalkalden was so pleased to see an English sightseer that she came round her desk to give me a hug.) Roper might have given us something to cling on to with the mind’s eye.

Her publishers describe her as “writing beautifully,” but this complicated story would have benefitted from more clarity of expression. One figure is introduced as Georg Truchsess of Waldburg, then as Truchsess Georg, then as “the truchsess,” and finally as “Truchsess,” as if it were his surname, and I had to resort to Wikipedia to understand what this name was. “Truchsess” is an archaic title, something like “seneschal,” I eventually discovered.

The Reformation certainly gave rise to a world in which the inconceivable became possible — Philip von Hesse argued forcibly (and even persuaded Luther) that the ban on bigamy was now overthrown, and he could marry his mistress without divorcing his wife. But we are not just interested in the teasing out of ideas or the explication of arcane pamphlets. We are interested, in a most vulgar way, in what people were like; what they were allowed to wear (how did sumptuary legislation specify the wardrobe of different classes?); and what the day-to-day progress of a savagely tragic war might have been like to experience. I have to say, too, that I find it difficult to commend an Oxford Regius professor for beautiful writing if she doesn’t know the meaning of “crescendo,” “ironically” or “enormity.”

However huge an impact the Peasants’ War made on the lives of hundreds of thousands, and however far it set back improvements to ordinary people’s lives, it needs to be explained with clarity and narrative enterprise. Roper has written an admired book about Luther. This one, I think, is for her professional colleagues.

Leave a Reply