Why did Bros bomb? The paltry $4.8 million opening weekend of the “first gay romantic comedy from a major studio featuring an entirely LGBTQ principal cast” — quite the mouthful — was as predictable as its fawning critical response (88 percent on Rotten Tomatoes). The film also cost $22 million to produce, not including its marketing budget, which somehow failed to publicize the fact that this is a rom-com from Judd Apatow.

When the film’s lead, Billy Eichner, announced that Bros flopped because straight people “just didn’t show up,” he was right — but it wasn’t just straight men; it was women who seemed as excited for Bros as they were the next sweaty and dim Rambo movie. Also, who titled this film? What was the logic? Women, especially young women, associate a “bro” with financial bros, space bros, gym bros and film bros. The marketing for Bros was practically chauvinistic in disregarding the most dedicated and loyal viewer of romcoms: women.

Ticket to Paradise isn’t a new masterpiece in the romcom genre either (56 percent on Rotten Tomatoes). It is a film lacking the precisely timed, snappy dialogue that turns stifled attraction into a delicious “battle of the sexes” scenario. It tries to do that, of course, but the flat writing turns the burning exasperation between George Clooney and Julia Roberts into a series of missed notes — nothing like the musical sparring of Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn, for example. As a tourism ad for Bali, it’s delightful: molten-orange sunsets over blue water, swaying palm trees, Julia Roberts’s incandescent smile, George Clooney’s marinating charisma. But it has a plot the Washington Post describes as “skimpy as a bikini.” You could argue that Bros is the funnier film — and yet none of that matters when you’re assessing box office appeal. “Skimpy as a bikini” is easier on the eyes than the “first gay romantic comedy from a major studio featuring an entirely LGBTQ principal cast.”

Ticket to Paradise opened to a domestic box office of $16.3 million and earned over $100 million globally. This is surprising, especially since the past decade has seen a period of downturn for the romcom — the theatrical romcom, to be more precise, has steadily declined in both ticket sales and market share since 1995, according to the Numbers.

If you look at the ten highest-grossing romcoms of all time, only one was released in the past decade: 2018’s Crazy Rich Asians. People were practically buying funeral bouquets for the genre when Jennifer Lopez and Owen Wilson’s Marry Me died at the box office ($8 million in its opening weekend). People have argued that the quality of the genre has suffered. It has. The last masterpiece romcoms with theatrical releases were Forgetting Sarah Marshall (2008) and 500 Days of Summer (2009). There were others, but those were notable in terms of quality and mainstream success. Ticket to Paradise isn’t as good as any of those films, but it’s performing like it is during a period of artistic and financial blight, particularly in the romcom genre, when even Jennifer Lopez cannot produce a big hit.

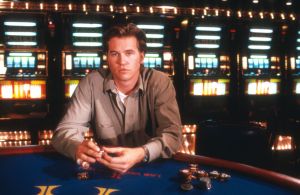

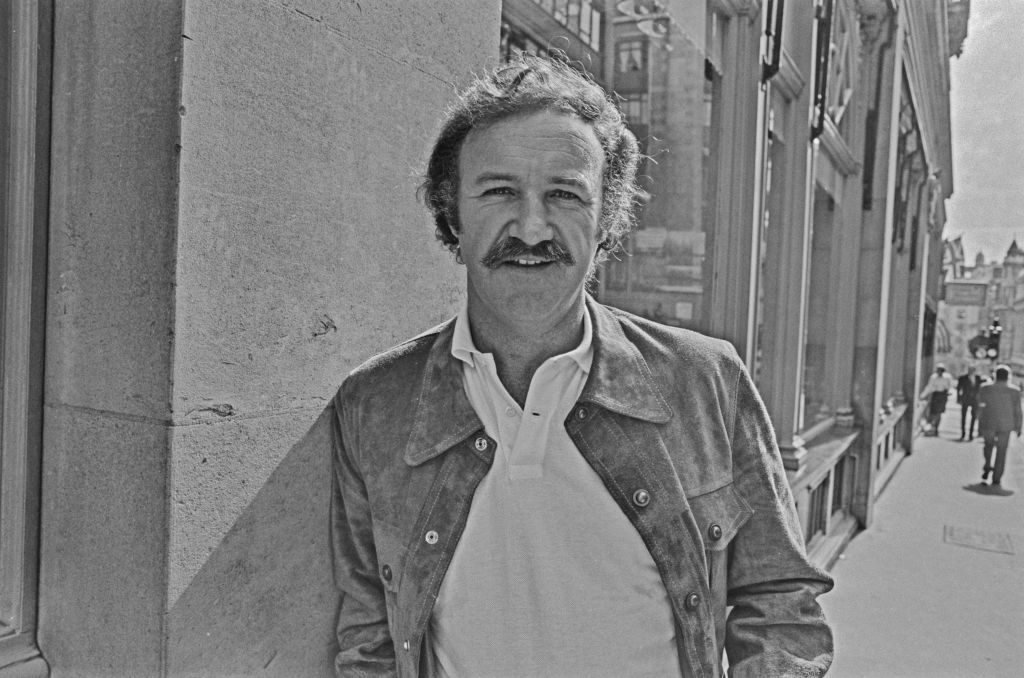

So how did Ticket to Paradise do it? The women who didn’t feel seen by Bros — especially women who grew up adoring George Clooney and Julia Roberts — flocked to the movies. I’m not one of these women, but I watched this film in a theater with some of them, who belly-laughed at every joke and cried as if they were little girls seeing Titanic for the first time. It was shocking, really, but it made sense. Ticket to Paradise was created for an audience that Hollywood has sort of forgotten: women of a certain age, divorcees, perhaps, who grew up subscribing to glossy magazines with Julia Roberts and George Clooney on the cover (People’s “Sexiest Man Alive” in 1997 and 2006, who has become more alluring and debonair with age, like Sean Connery, who was “Sexiest…” at fifty-nine).

But what else contributed to this? The country is (frankly) a little melancholic, and it needs movie stars and accessible plots, with all the tropes and clichés, as smooth and unserious as drinks with umbrellas in them. Audiences want to escape as desperately as they did during the Great Depression. They don’t always want superheroes or CGI. They want movie stars. They want glamorous stars they have a certain nostalgia for and plots that take them as far away from the news cycle as possible (Bros drowned them in it).

The numbers also support a need for more romance in the marketplace: 1) Americans are less likely to get married than ever before; 2) A rising number of people live alone; 3) Americans are less likely to have sex; 4) The pandemic produced a boom in sales of romance novels. This is crucial.

In other words: America is turning into an Ed Hopper painting, but it needs a Nora Ephron ending. This fog of melancholy (and a faint glimmer of romance beneath it) could fuel a new romcom boom, assuming Hollywood consistently packages these films with movie stars, throwback plots, glamor, sex appeal and screenplays that do not ignore the romcoms target demographic: women who want to swoon.