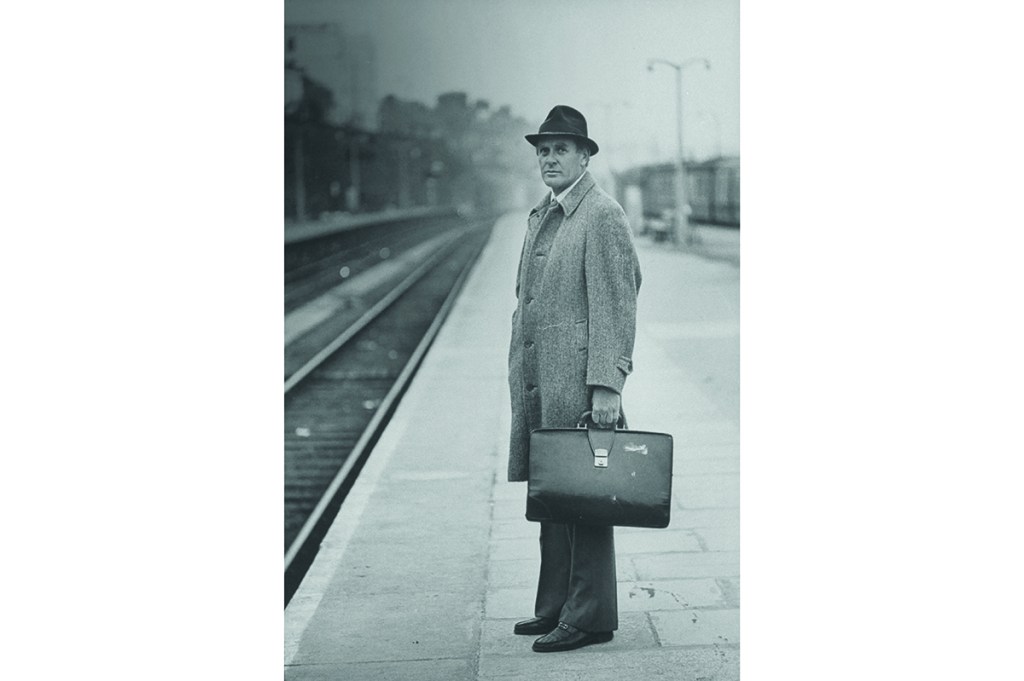

I started reading Suleika Dawson’s The Secret Heart at a London bar, intending simply to skim through as I finished my beer. Six hours and many more beers later I was still at the bar, and still reading. The book, an erotically charged, no-punches-pulled account of her multiple affairs with the author John le Carré (or David Cornwell, as she knew him), is also a fascinating and important portrait of the man himself. The pseudonymous author, with her winking nod at Max Beerbohm’s femme fatale, offers a degree of insight and honesty which le Carré’s official biography (let alone his own memoir) and recently released collection of letters do not, and a character study of a London long since lost. It is a far cry from the post-pandemic grayness, moral puritanism and looming austerity of today.

Dawson herself is all that you’d hope for and more, as I discover when we meet. Standing at a statuesque six feet, her conversation gives evidence of a fierce and world-weary intelligence, with a cut-glass accent and refined drawl that give her a voice like a velvet whip. Her narrative of a young, beautiful, twenty-something Oxford graduate navigating the pulsing world of TV and Soho media in the Eighties is an enticing one. Talking to her is a rare delight.

As she says, “Soho felt like such an exciting, impossibly open world then. I was a tall, blonde city girl not long out of college and generally up for anything. I lived in Chelsea, worked in the West End as a freelance program researcher, and shopped in Knightsbridge. Everything in my world was wonderful. David simply offered to make it more wonderful, with that fizz of excitement and intensity he supplied and the way he insisted it was all just for me.”

She first met le Carré in September 1982, when the man himself was brought in to narrate her abridgment of Smiley’s People for one of the early audiobook producers. After the second day of recording, he took her to a nearby restaurant, bought her everything on the menu with accompanying Champagne, and “hailed an oncoming taxi, which promptly drew up. Then, without prelude, he kissed me urgently on the mouth, turned to the taxi, heaved open the door and got in.” It would be almost a year before they met again.

They were reacquainted in September 1983 when she adapted The Little Drummer Girl. For the next two years, they embarked on an intense love affair, working intimately together, with Dawson le Carré’s literary researcher for A Perfect Spy, his most autobiographical novel. She writes in The Secret Heart that “it was as if we had always been lovers. There was no shyness between us, only an infinite familiarity. This was sex as I had never encountered it before, the sex I had determinedly pursued all my adult life. This was sex that only the hero and heroine can have; sex for the cameras, sex for the Olympics, sex for the gods.”

When their romance came to an end in 1985, Dawson returned to her freelance television work and published her own novel. It would be almost fifteen years until the affair reignited briefly in 1999, before abruptly ending again, once and for all. Today, she says “I’ve withheld a few details to spare some blushes — most of them my own — but otherwise this is a pretty full account of what has unquestionably been one of the most significant relationships of my life. Of his too, I like to think.”

The British book critic Jennifer Selway praised Dawson for “not pulling the #MeToo card” and, despite being twenty-five years le Carré’s junior, for never portraying herself as a victim. “I’d never realized that I hadn’t ‘played the #MeToo card,’ simply because I would never have thought of playing it in the first place.” Rather than casting herself as the exploited ingénue, Dawson embraces having made her own mistakes and her own successes, and enjoying things that now aren’t supposed to be enjoyed. The fact that this has proved so controversial is not something she was prepared for.

“It shows what’s been lost in this filter that everything has to go through now,” she says. “It’s too easy for the wrong people to take advantage of the wrong side of what ought to be a regular issue. There’s a whole load of stuff that I think nowadays can’t be said, and I think it’s dangerous. It’s why we live in a world where Donald Trump is coming back, a world of increasingly unrecognizable types of people, who have been so long in their bubbles that they’re unable to identify what objective truth is. Well, perhaps they can identify it, but they don’t seem to care to. Perhaps that’s the point. They no longer require it.”

It is easy, of course, to rose-tint the past — especially when focusing on the fun and the frolics — but Dawson doesn’t fall prey to Golden Age thinking. “Isn’t it wonderful that people aren’t molested in their offices anymore? I was groped by [the Australian cartoonist] Rolf Harris once, when I worked in television. It wasn’t nice, but it was also nothing to be triggered by. It was just a dirty old man on the other side of the green room. It wasn’t shocking and horrible, it wasn’t traumatic. It was just disgusting.”

One could argue that a culture of self-justification, subjective “truths” and silenced voices led to the very abuses #MeToo arose to combat. The hypocrisy of those institutions that now seek to appear progressive is not lost on Dawson. She speaks with anger. “I knew about Jimmy Savile in 1980, when I was dating some big executive who’d just left the BBC in disgust. We were talking about telly in general and Savile came up, and he said, ‘Oh yes, you know he has caravans around the Spinal Unit, and patients come and go, and there’s nothing you can do about it.’ So all the people since who’ve said, ‘we didn’t know’ — Rubbish! They all knew. If I knew about it as a girlfriend, everybody would have. To deny it so openly and get away with it! If they were a private corporation, they’d have been shut down.”

She continues with resignation. “I mean, the laws were still there. I don’t believe the laws have changed radically. It was always possible to ostracize these types. It was just that it never happened, and it never hap- pened, I think, through a conspiracy of not too dissimilar-minded men.”

It’s the boys’ club hypocrisy that has frustrated her most in the critical response to her book. “Apart from all the vitriol, it’s the arrogance of feeling to it! Aging, white-male angst, I put it down to. The pearl clutching! It seems to me there’s an artificiality to it. I think maybe there’s a nerve that I touched in aging British writers who still think that this sort of tell-all is just ‘not what you do,’ perhaps in case it gets done to them. Or possibly because it never got done to them. I do think many of them just never had these relationships that I’m writing about. These guys were just bystanders — however much they might think they’re the movers and shakers — and they’re simply jealous.”

Despite the upturned noses, The Secret Heart is far more than cheap titillation. “I made a point of positioning myself in the line of Sheilah Graham and Mary Welsh Hemingway and Carole Mallory,” who famously published accounts of their relationships with F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway and Norman Mailer, respectively. “I hope I’ve made him seem as lovely as he was and as loving. I hope I’ve shown the magic. I trust I’ve helped elucidate the rest.” She has. Dawson’s book is an important addition to the burgeoning canon of le Carré studies. Yes, it is suffused with sex, decadence and the peaks and troughs of a life lived to the hilt, but then so was he.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2023 World edition.