Fifty years ago this midsummer, a ramshackle convoy of vehicles — cars, minibuses, motorcycles and the odd hippie caravan — could be seen wending its way through the western counties of England in search of a patch of agricultural land near Shepton Mallet called Worthy Farm. There had already been several Sixties-era tribal gatherings in the fields beyond Michael Eavis’s now legendary homestead, but this iteration, widely advertised in the countercultural press, came billed as the very first Glastonbury Festival.

The 12,000 or so music fans who made it to north Somersetshire were treated to a lineup that featured Joan Baez, a pre-fame David Bowie and psychedelia veterans Traffic, and would have included headlining act Pink Floyd, had they been able to winch their equipment up onto the rickety stage. Further down the bill, rock cognoscenti would have noted the presence of such left-field esoterica as Quintessence, Henry Cow, Gong and, putting all these acts to shame in their pursuit of extra-terrestrial weirdness, a little-known ensemble named Hawkwind.

Hawkwind! Even to type the word on a computer screen is to conjure up a paralyzing vision of black leather, naked dancers, synthesizer-heavy space-boogie (what the critic Lester Bangs called ‘music for the astral apocalypse’) and volume levels set to stun. Nearly five decades later, I can still remember the first time I set eyes on them — July 23, 1972, to be precise, when, with maximal incongruity, they appeared on the pre-eminent primetime UK music show Top of the Pops. In an era of glam rock and sensitive balladeers, nothing could have prepared the TOTP audience for what followed. Moments earlier in the program, Little Jimmy Osmond had assured the nation’s girlhood that he would be their long-haired lover from Liverpool. The Pan’s People dance troupe had shuffled their way through the Stylistics’ ‘Betcha By Golly, Wow’. The emcee, Jimmy Savile (then regarded simply as an oddball rather than a predatory pedophile), had murmured a few introductory remarks and suddenly there they were, beamed out via promo video from a live gig somewhere in the Home Counties of England, churning through what was to be their only chart single, ‘Silver Machine’.

The footage, available on YouTube, bears watching even now, not so much for the music — scuffed-up Chuck Berry riffs with spaced-out caterwauling — as for what John Fowles once called the ‘visual oomph of the mimesis’. For this, purists agree, is the ‘classic’ early Seventies line-up. ‘Miss Stacia’, a Junoesque, and on this occasion fully-clad, six-foot two-inch former gas-station attendant, limbers up at front of stage. Emaciated drummer Simon King flails desperately away. The two sonic technicians — Dikmik (real name Richard Michael Davies) and Del Dettmar — are hunched over their synths and oscillators. Auburn-haired flautist Nik Turner and guitar-playing band leader Dave Brock lurk modestly in the wings, as bassmeister Ian ‘Lemmy’ Kilmister, long-haired, leather-clad and the epitome of what is then known as biker chic, leans up to the mic to hoarsely intone what appears to be a strew of sci-fi lyrics about flying sideways through time, electric lines and zodiac signs.

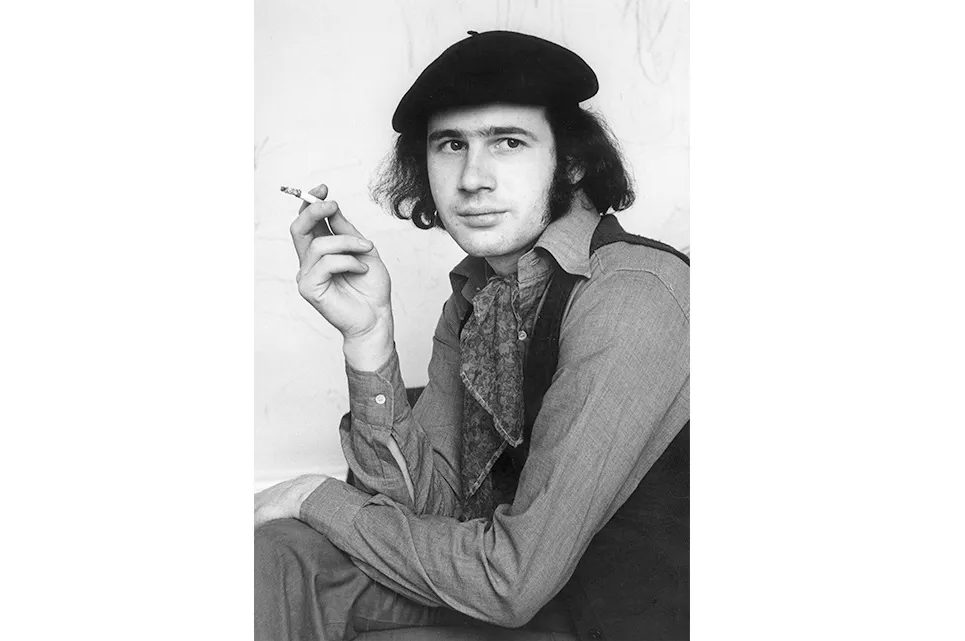

There is one conspicuous absentee among what Michael Moorcock once called ‘the crew of a generation-long spaceship gone completely nuts in the process’. This is the song’s cowriter Robert Calvert, currently being treated for bipolar disorder, whose stage presence, replete with aviator shades and burnous, will later be described as a cross between W.E. Johns’s fictional pilot Biggles and Lawrence of Arabia with S&M undertones. Yet even without Calvert, whose ‘silver machine’ will later be revealed as the bicycle on which he cruises the streets of west London, the spectacle of Hawkwind on Top of the Pops is well-nigh unprecedented.

Rarely in those far-off days — this was the Britain of Edward Heath’s Conservative government, gearing up to enter the European Union — did you get a glimpse on primetime television of the chaotic, countercultural world that existed beyond its margins. Yet here, indisputably, it was: a sharp, nostril-distending whiff of a landscape made up of squats and alternative communities, free festivals, White Panthers and drug-dealing in west London’s hippy caravanserai, Ladbroke Grove. Unlike most smoke signals from the underground, ‘Silver Machine’ hit number three on the singles chart, sold 500,000 copies in Britain alone and might, in ordinary circumstances, have propelled its makers to sustained commercial success and international celebrity. That it didn’t is a testimony to, first, the kind of people Hawkwind were, and, second, the musical and cultural scene from which they sprang.

The distinguishing mark of Anglo-American popular music from the mid-1960s onwards, at all times governed by the Beatles and the route they were taking, is its exponential rate of change. As somebody once remarked, if the novel took nearly 200 years to produce such mid-Victorian titans as Dickens, Melville, Hawthorne and George Eliot, then pop music, from the moment Elvis arrived, went from 0-60 m.p.h. in a few incident-packed years. Beat groups gave way to Mods, and no sooner had sharp-suited, bouffant-haired gangs of Rickenbacker-toting teenage hoodlums such as the Who and Small Faces finessed their way into the recording studios than a new kind of music came barrelling up on the margin. This was psychedelia — consciousness-raising and drug-fueled, musically a matter of woozy mellotrons, chiming guitars and nursery rhyme lyrics — and a dominant force in English pop from the moment the Beatles recorded Revolver in 1966. By 1967, the year of Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Pink Floyd’s Piper at the Gates of Dawn, psychedelia was, like many another dominant force in English pop, ripe to be assimilated into the cultural mainstream.

‘They’re selling hippie wigs in Woolworth’s’ drug-dealing Danny protests in Bruce Robinson’s cult classic Withnail and I (1986), set in the last days of 1969 and lamenting the end of a decade, which, to borrow Thom Gunn’s famous lines about Elvis, had simply revolted into style. To listen to some of the box sets which commemorate English psychedelia — these have titles like Let’s Go Down and Blow Our Minds: The British Psychedelic Sounds of 1967 — is an odd and ultimately rather dispiriting experience, for at their heart lies a series of exercises in cultural cannibalization, in which all those present (erstwhile Beat groups, male-voice choirs, assorted rhythm & blues singers) are merely imitating a prevailing form. All this produced a certain amount of confusion, as when a one-time jug band called the Purple Gang supposedly had a record entitled ‘Granny Takes a Trip’ banned by the BBC for allegedly encouraging drug use. In fact, Granny’s annual ‘trip’ is to Hollywood to audition for movies in which she stands no chance of appearing.

What happened to English psychedelia after the late-Sixties high tide? If one branch of it swiftly mutated into the ‘progressive rock’ stylings of Pink Floyd, Yes, Genesis and Emerson, Lake & Palmer, then another branch simply went back to its countercultural roots among the hippie happenings of the pre-Sgt Pepper era. The mark of this phase in the postwar British alternative lifestyle is its resolute informality. For every countercultural landmark — the Albert Hall ‘Poetry Olympics’ of 1965, the founding of the London Free School in Notting Hill in 1966, the Indica Bookshop in Mason’s Yard, St James’s, at which celebrity patron Paul McCartney could sometimes be seen browsing the shelves — there were dozens of groups of society-disdaining nonconformists bent on living their lives as they chose. To Moorcock, who moved to the Portobello Road area of west London in 1963, and whose sci-fi magazine New Worlds shared typesetters with such staples of the underground press as Oz and the International Times, it was as if the counterculture ‘grew up around us’. Most of Hawkwind’s early personnel hailed from this tatterdemalion demographic. Brock had spent much of the previous decade busking in Ladbroke Grove; Turner had dabbled in free jazz; Lemmy, meanwhile, had knocked around various Sixties groups with names like the Rockin’ Vickers before roadie-ing and scoring drugs for Jimi Hendrix.

In the early 1970s there was plenty more longhaired alternative music keen to disrupt the relative conformity of the BBC singles chart — one might mention the Edgar Broughton Band with their signature chant of ‘Out Demons Out!’ What made Hawkwind the UK’s leading ‘underground’ band? One factor was their absolutely prodigious drug intake. Lemmy later admitted that Dikmik, a fellow amphetamine addict, had invited him to join the group merely for the satisfaction of having another drug buddy on the strength. Ticket holders at their early gigs could expect to find vials of liquid LSD distributed gratis at the door. Guitarist Hugh Lloyd-Langton, who played with them at the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival and was handed a glass of spiked apple juice just as he went onto the stage, suffered a demonic visitation so mind-blowingly profound that he sank to his knees and prayed for deliverance. ‘That was really cool,’ an admiring Turner is supposed to have told him. ‘You should do it every night.’

Item two was their self-proclaimed status as a ‘people’s band’ who intended to stay as close to their original audience as possible, avoid fancy, high-end studio production techniques (critics who complained that the records seemed ragged and under-produced were informed that they were meant to sound that way), play free concerts and espouse every good progressive left-wing cause then on display. Ideologically, this meant very little — Moorcock recalls that ‘their politics were more sentimental than intellectual’ — but it was the cause of constant intraband friction, with Lemmy complaining that Calvert was ‘always trying desperately to be a radical and he was just a suburban young man’ and even sympathizers noting the band’s habit of losing money on benefit gigs in far-flung parts. Still, in their Ladbroke Grove days Hawkwind hung out with some very heavy people, from the Hells Angels to the Angry Brigade, a home-brewed anarchist group of bomb makers, and recorded a Calvert-penned single called ‘Urban Guerrilla’ (‘I’m an urban guerrilla/ I make bombs in my cellar’) whose political implications were sufficiently alarming to have Turner’s flat turned over by Special Branch police.

There are fascinating parallels between what was going on in the as-yet ungentrified back end of west London, beneath the towering stanchions of the M40 motorway, where the band played free gigs powered by a portable generator, and similar stirrings taking place in the American Midwest. In his recent memoir The Hard Stuff (2018), Wayne Kramer, guitarist with Detroit’s incendiary proto-punk five-piece the MC5, noted that ‘the last thing we were was a serious political entity’. And yet Michigan’s finest, managed by the White Panthers’ supremo John Sinclair and with a manifesto advocating ‘Dope, Rock & Roll and Fucking in the Streets’, found themselves fraternizing with such ornaments of the activist scene as the Weathermen and the International Werewolf Conspiracy. There was a particularly scary moment at the Fillmore East when the band informed a crowd packed out with members of a militant cabal known as the East Village Motherfuckers that they hadn’t come to New York for the politics but to play rock ’n’ roll, and narrowly escaped from a revolutionary mob.

If nothing quite like this ever happened to Brock & co. — usually happier playing summer solstice festivals to audiences of blissed- out simple-lifers — then there were still occasions when the politics and the entertainment factor collided head on. ‘This is for the righteous people,’ Turner declared, surveying the thronged audience of the Empire Pool, Wembley (now the Wembley Arena) at the height of their success, only to be undermined by Brock’s insistence that ‘We’ll have a general jam tonight.’ And yet much of the material on their early albums — Hawkwind (1970), In Search of Space (1971) and Doremi Fasol Latido (1972) has an unmistakable political charge. Hawkwind: Days of the Underground, Joe Banks’s exemplary 500-page take on the band’s activities in the 1970s, is subtitled ‘Radical Escapism in the Age of Paranoia’. This neatly conveys the anti-authoritarian and deeply warped futurism in which Hawkwind dealt, the thought of what Turner called ‘this terrible authoritarian future’ stealing up on the margins of civilized life.

Unusually in a medium not known for its literary associations, the framework in which Hawkwind’s music established itself was dystopian sci-fi. By this point, a decade and three-quarters into modern pop music’s existence, there had already been one or two engagements with science fiction, or what some of the new breed of Sixties practitioners preferred to call ‘science fantasy’. If the title of the Pretty Things’ pioneering rock opera S.F. Sorrow (1968) refers to its hero, Sebastian F. Sorrow, then it also gestures at the lunar trips and extra-worldly adventures that punctuate Sebastian’s career. Meanwhile over in the States, George Clinton’s Funkadelic was in the process of minting a brand of genuine black sci-fi in which Motherships packed out with partygoing astronauts descended to earth to unleash ‘the Funk’ on a wide-eyed world. Nobody, though, set to work with as much deliberation as Hawkwind; neither did anyone find himself harnessed to such a top-of-the-range collaborator as Michael Moorcock.

Born in 1939 and a year or two older than most members of the Hawkwind tribe, Moorcock was, unless you admit J.R.R. Tolkien to the genre, probably the bestselling science fantasy author in the UK in the early Seventies. He was also, in an art world keen on preserving literary hierarchies, one of the most respectable — up there with J.G. Ballard as a writer that mainstreamers who didn’t condescend to read science fiction would have heard of. Contacted by Calvert, who wanted to involve him in In Search of Space, Moorcock, describing his collaborators as ‘barbarians with electronics’, began by performing a spine-chilling piece called ‘Sonic Attack’ (‘an ongoing narrative of the future’ inspired by Cold War public service broadcasts) in a tiny theater erected under the motorway. ‘They had a barmy, visionary innocence,’ he later recalled. ‘All the other psychedelic bands seemed pretentious and pale in comparison.’

With ‘Silver Machine’ and two top-20 charting albums behind them, the stage was set for Hawkwind’s finest hour: a touring production, ‘The Space Ritual’. According to Calvert, interviewed by a music paper shortly before it took flight, ‘The basic idea is that a team of starfarers are in a coma, a state of suspended animation, and the opera [sic.] is a presentation of the dreams they’re having in Deep Space. It’s a mythological approach to what’s happening today.’ The songs have titles like ‘Black Corridor’ (again from a Moorcock novel), ‘Born to Go’ (‘We were born to go/ We’re never turning back/ We were born to go/ And leave a burning track’) and ‘Brainstorm’, and the experience, captured on the album Space Ritual in front of an ecstatic live audience, sounds like, well, dinosaurs tussling on primeval mudflats, the highly amplified scuffles of furry animals, eldritch shrieks above an endless, thumping, electronic drone.

One talks about the Hawkwind ‘audience’, but this by-now substantial constituency had several layers. The old Ladbroke Grove camp followers from the days of the free concerts and the International Times — all those Sixties survivors emerging into the light of a much less hospitable world — mingled with anarchists, biker boys and edge-of-town flotsam, but also younger rock fans who appreciated the very loud noise they made and enjoyed the multimedia spectacle of Stacia’s dancing, atmospheric lightshows and the influential rock artist Barney Bubbles’s sci-fi graphics. The band themselves noted how well they went down in Britain’s industrial north (half of the Space Ritual album was recorded in Liverpool) and the crowd members seen writhing energetically in the ‘Silver Machine’ promo approximate to the traditional audience loud music in the early 1970s: young people looking to let off steam after a hard day at factory or foundry. High-minded music-press critics generally deplored them, but to a certain extent this was part of the attraction. In a curious way, not unknown in the history of popular music, their sheer unfashionability kept them alive and kicking.

Up to a point, that is. Space Ritual, which reached number nine on the UK album chart in 1973, was the band’s high-water mark. Thereafter the road stretched, if not down and ever down, then into some highly abstruse and unregarded back alleys. Part of it was to do with the nature of the band — seldom a strictly demarcated contingent of musicians with clearly defined roles, more of an alternative rock commune sloughing off personnel and replacing them from one recording session to the next. To the inevitable musical differences (‘The geese are flying south,’ Lemmy would routinely sneer whenever Turner’s saxophone started up) were added personal tensions and a suspicion that certain members were keener on filthy lucre than sticking it to the man. Stacia left to get married. Dettmar and Dikmik seem to have departed out of sheer boredom. Lemmy was fired in 1975 after a drug bust at the Canadian border. Calvert, always an erratic presence by virtue of his mental state, came and went. By the late 1970s, of the original cohort only Brock remained.

As for their afterlives, Lemmy, famously, founded the internationally successful Motörhead, relocated to Los Angeles (where he became a minor tourist attraction) and, despite heroic levels of amphetamine consumption, died as recently as 2015. Calvert made solo records, recorded novelty songs, married his friend Moorcock’s first wife, wrote — among much else — a novel entitled Hype and was dead by his early forties. Those wanting a portrait of him in his prime are directed to the YouTube footage of the band playing a number called ‘Quark, Strangeness and Charm’ on Marc Bolan’s TV show in 1977. The subject is Albert Einstein and yes, that is a stuffed parrot taped to Calvert’s wrist. Its existence constantly endangered by line-up changes and the threat of legal proceedings, an entity still known as Hawkwind persists into 2021. Their Wikipedia discography extends to 86 items, and the number of musicians thought to have passed through their ranks in the 52 years of their existence must now be in the low hundreds.

Why is all, or indeed any, of this important? One reason, naturally, is to do with influence. Many a rock ’n’ roll noise merchant of the succeeding decades looked to Hawkwind as a source of inspiration. Several of the punk rockers of the later 1970s turned out to have attended their gigs. When Johnny Rotten was formally introduced to Lemmy as a Sex Pistol, they recognized each other from Hawkwind gigs, and when the Pistols reformed for a string of live concerts in the early 2000s, they made sure to open the show with a reworking of ‘Silver Machine’. Among American flagwavers, Henry Rollins is supposedly a fan; the Foo Fighters’ Dave Grohl spoke at Lemmy’s funeral. And then there is the electronic end of the band’s undoubted impact on the dance and rave scenes of the 1990s, their lawbreaking free-festival feel, their pulsing rhythms and ambient swirlings. Certainly the unusually restrained opening sequence of ‘Assault and Battery/The Golden Void’ (hopping bass notes, synthesizer wash) from 1975’s Warrior on the Edge of Time sounds about 20 years ahead of the era in which it was forged.

More vital still, perhaps, is what Dave, Lemmy, Nik and the others might be thought to represent. After all, their creative heyday was the early 1970s, when most British popular music had been thoroughly commercialized and welded to mainstream taste and most British life ran in a highly conventional groove, a world of three television channels, two political parties and a raft of settled assumptions which it seemed nothing could alter. Here, suddenly, was hard evidence of a community that existed outside the palisade, away on the margins, down there in the debatable lands beyond straight society, a demonstration that all the habits that had taken root in the 1960s hadn’t disappeared but merely taken on different shapes.

To return the argument to the level of aching personal preference on which all pop criticism ultimately depends, I may not have actively liked Hawkwind’s music back in 1972, and I may not like it now, but somehow there is an odd kind of satisfaction in the knowledge that it and its creators were always there — a permanent thorn in the flesh of pop orthodoxy, a reminder that here among the sanitized landscapes of contemporary music there is still space for the keening left-field voice, the exotic visitation from worlds unseen and, at times, the frankly crazy.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2021 World edition.