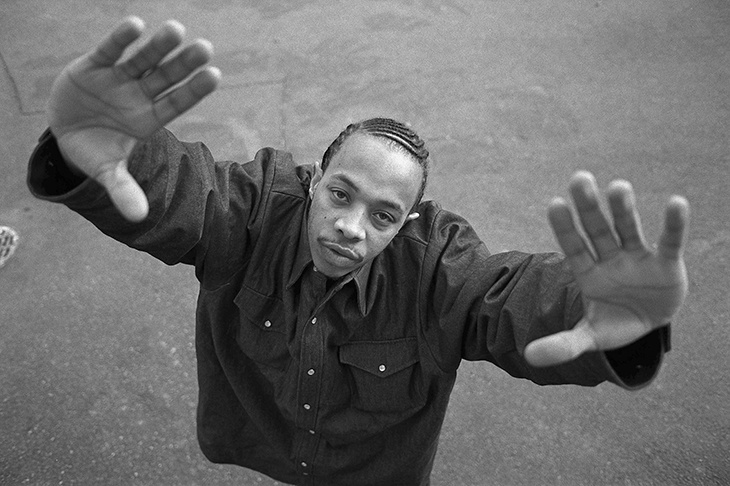

I’ve interviewed a lot of rappers over the years and always feel a little grimy when I find myself nudging them to repackage a horrendous experience as a juicy anecdote with which to promote an album. Some natural raconteurs are happy to play that game — 50 Cent can now tell the story of the day he was shot nine times with the fluency of Peter Ustinov on Parkinson — but many rappers are understandably coy, at least outside the recording studio, about sharing the gory details of their previous lives. In that respect, this memoir by one of the nine original members of the Wu-Tang Clan lives up to its title, being so brutally frank that it is hard to believe a single story remains untold.

Masterminded by Robert ‘RZA’ Diggs, the Wu-Tang Clan made hip-hop’s standard menu of braggadocio and true crime intoxicatingly strange via a private language comprised of Marvel comics, kung fu movies, obscure 1970s soul and the esoteric Islamic doctrine of Supreme Mathematics. In their arcane psychogeography, Staten Island, the runt of New York’s five boroughs, became mystical Shaolin, and the streets became a mysterious labyrinth of allusions, in-jokes and codes. They have never trumped the dread power of their initial appearance on the cover of their debut album, 1993’s Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), with their black hoods, blank white masks and smoggy aura of cult-like menace. While their contemporaries sought to project street-level authenticity, the Wu-Tang Clan bent reality.

The group’s mystique has been sorely depleted over the past 25 years and Lamont ‘U-God’ Hawkins finishes the job. He is not a mystique guy, nor is he likely to be confused with Proust. ‘Time is a motherfucker,’ he begins. ‘Time reveals shit.’ Lightly ghostwritten by John Helfers, Raw reads like a pungent, profane 290-page monologue about a life with nothing but rough edges.

Hawkins grew up in Staten Island’s Park Hill housing projects during the 1980s crack epidemic that earned the area the nom de guerre Killa Hill. A child of rape, he was arrested, beaten, threatened at knifepoint by his mother’s partner, molested by his babysitter, addicted to crack-loaded joints and almost murdered five times by rival drug dealers, all before he turned 18.

While Kendrick Lamar, a much more sensitive soul, has talked about survivor’s guilt and PTSD, Hawkins is chillingly unsentimental about the tribulations that he survived and many of his peers did not. An anecdote about one man who crossed him concludes with this blunt coda: ‘Last I heard, he wound up doing 15 years for heroin possession, then came home and died of Aids.’ Well that’s that, then.

At one point Hawkins planned to train as an embalmer because he had become so anaesthetised to the sight of dead bodies. ‘We’re all just bone men,’ he says. ‘We ain’t nobody. We’re so fragile.’ It’s no surprise that, like so many rappers of his generation, he was attracted to the Five Percenters, a baroque offshoot of the Nation of Islam. When you’ve had this many close shaves, you’re prone to believing that God has other plans for you, even if that religiosity does not, in Hawkins’s case, appear to have inspired much soul-searching.

While most music memoirs compel you to race through the early years to get to the meat of the story, Raw actually loses momentum once Hawkins trades crime for rhyme. You’ll learn more about the crack business (top tip: get up early to catch the dawn rush) than you will about the music industry. Hawkins only made a fleeting appearance on Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) because he was serving time for drug and firearm offences, and never made it to the top table. Nor did he become wealthy enough to entirely escape the streets.

Even as he hung out with Mike Tyson and juggled a dozen girlfriends (‘fuckin’ hard work,’ you won’t be surprised to learn), he suffered a breakdown after almost losing his two-year-old son to a stray bullet. Keen though he is to insist that the Wu-Tang weren’t ‘derelict thugs that got lucky’, Hawkins’s grim catalogue of casual violence and festering rancour is hardly edifying. Concluding with several plugs for its author’s ongoing lawsuit against RZA, Raw is ultimately as disillusioning an account of life in a beloved group as the Fall bassist Steve Hanley’s The Big Midweek. Better than the alternative, clearly, but some distance short of inspirational.

Where Raw becomes truly illuminating, and even touching, is in Hawkins’s realisation, after touring the world for the first time, that the environment he left behind was so very small. He drives past his old battlegrounds, where dealers fought and died for control of a few square metres, and finds those buildings blandly silent, inspiring a sense of futility and regret that he can barely articulate. ‘It was all over nothing,’ he says. ‘It all meant nothing.’