“No, Lisa.”

As rejection letters go, it was admirably concise. I’d made an attempt at “autofiction,” that amorphous genre which inhabits the space between autobiography and fiction, and this was the entirety of my editors’ response. Any writer who has been at it for any length of time will have received Dear Johns from publishers, but is two words a record? It was something to cling to, at least, during the five further years it took for the book to find a home. Eventually, a French house took it, and Les Femmes de mes amants staggered unobtrusively into print in June this year.

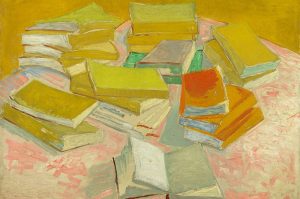

Obviously, I should have set my sights on Paris from the first. The long-standing prestige of autofiction in France has now been vindicated with the awarding of this year’s Nobel Prize for Literature to one of its most radical practitioners, Annie Ernaux. It arguably goes back as far as Montaigne’s Essais, or at least to Proust, but the term itself was introduced by Serge Doubrovsky in 1977. Defining it as “a variety of different practices which tend towards the conciliation of information and the freedom of narrative writing,” Doubrovsky claimed that autofiction embodies modern sensibility in a particular, fluid fashion.

It was a prescient assertion; long before scripted TV “reality,” curated Instagram feeds and deep fake photography, autofiction was attempting to grapple with the notion of that the very concept of the “self” as mercurial, mutable and fictionalized in the very act of its determination. The concept of an objectively delineated, pre-existing reality which a writer might choose to fictionalize might in itself be illusory, since it is the stories we tell to and about ourselves which shape the “fable” of our own existence. As Jules Renard put it, “As soon as a truth exceeds five lines, it’s a novel.”

French writers of autofiction including Catherine Millet, Virginie Despentes, Ernaux, Édouard Louis and Delphine de Vigan have been successfully experimenting with the genre for some time. De Vigan’s 2016 novel D’après une histoire vraie was explicitly positioned as a challenge to the shortcomings of the novelist’s whimsy when confronted with the demands of highly sophisticated readers attuned to the interplay of fact and fiction:

People have had enough of well-oiled intrigues… (which) multiply stories to sell them books, or cars, or yoghurts… Readers want something different from literature and they’re right, they expect the Real.

What the “Real” is, and the extent to which the autofiction writer is justified in addressing it, became a familiar source of controversy in the Anglosphere with the publication of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s six-volume series My Struggle. Virkelighetslitteratur (“Reality literature”) also has a long tradition in Knausgaard’s native Norway, a founda- tional work being Knut Hamsen’s 1890 Hunger, but as My Struggle achieved international bestseller status the ethics of the practice were called into question.

The critic Marta Norheim noted that Knausgaard’s writing was exceptional for its “merciless quality” toward himself, but the moral legitimacy of exposing others to similar psychological flaying was hotly debated. “When I finally did it,” claims Knausgaard,“it felt like a huge transgression… when the qualms became too many, I refrained.” Not sufficiently for the author’s uncle, who campaigned successfully to have his name changed in the books. Emmanuel Carrère encountered a similar dilemma with his recent “nonfiction novel” Yoga, which had to be radically cut to conform to an NDA which demanded the excision of all passages referring to his ex-wife.

To qualify as autofiction, a work’s protagonist and its author must conventionally have the same name. Beyond that, there are relatively few rules beyond (perhaps) a disregard for plot and a privileging of theme over chronology, to which one might add an exploration of the aesthetic potential of the banal and the ugly. So how did it feel to do it? The Real might, in de Vigan’s words, “have the balls to go much further,” but how to decide how far to go?

I did attempt to educate myself about the genre before embarking on my book, but revisiting Roland Barthes recalled an undergraduate nightmare; the effect of the Real “concerns an element which clearly indicates to the reader that the text is clearly attached to the description of the real world, an element whose function is to affirm the clear relation between the text and reality.” Since that wasn’t at all clear, I decided that I could only correctly own my personal experience on the page. What’s happened to me is mine but anything I hadn’t directly seen or heard is not my property. Not being “allowed” to make anything up was weird.

Weird and interesting and really, really difficult — the connections between the observations and occurrences in the story could be imagined, but not the self who recounted them. Some passages were so raw that I felt physically ill as I wrote them and they went into the text as one-offs, unedited. That sounds horribly pretentious, but try thinking of the very worst thing that’s ever happened to you. Write it down. Don’t spare the details. Then see how you feel. Autofiction is emphatically not therapeutic; it makes no attempt to distance the writer from what she knows, rather it renders it more real. Hence more messy, more scary, more complex: a 100,000-word exercise in picking a scab.

Which is not to say that autofiction needs to be misery memoir. One of the freedoms I discovered in writing Les Femmes de mes amants was being able to explore moments — acute maternal love, giddily exhilarating adventures with girlfriends — and record them neat, without attempting to transpose or impose them on invented characters. The rigor of attempting to set down reality made me realize how undisciplined my technique had been before, and to question the boundary between imagination and narrative sloppiness.

Novels obviously have their own myriad challenges, but I’ve never bought into the idea that characters run away with writers’ conscious intentions. In autofiction, however, they became considerably more unmanageable, boisterously autonomous. Sometimes they insisted on appearing, ghosts which I had much rather stayed laid. So was the result any more real? Maybe. Autobiography is no less crafted, molded or awash with agendas than autofiction. Perhaps the latter is simply more open about the lies we tell ourselves.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2022 World edition.