Three projects shedding light on the sacred music of J.S. Bach are nearing completion. The first consists of an epic twenty-five-year project to record all the composer’s vocal works — passions, masses, motets and 200-odd cantatas — in electrifying performances supplemented by lectures and workshops. At the helm is a Swiss choral conductor renowned for his improvisatory skills — and surely the only baroque specialist to have played Sidney Bechet on a chamber organ.

The second project is a guide to Bach’s church cantatas tailored at “cultural Christians”; that is, music-lovers intrigued but intimidated by their Lutheran theology, unsure how to approach this treasure trove of, at a conservative estimate, more than 100 masterpieces of western civilization. It’s in three volumes, the first of which will be published this spring. The author is an English grandmother who, despite never having held an academic post, is one of the great musical polymaths of our time.

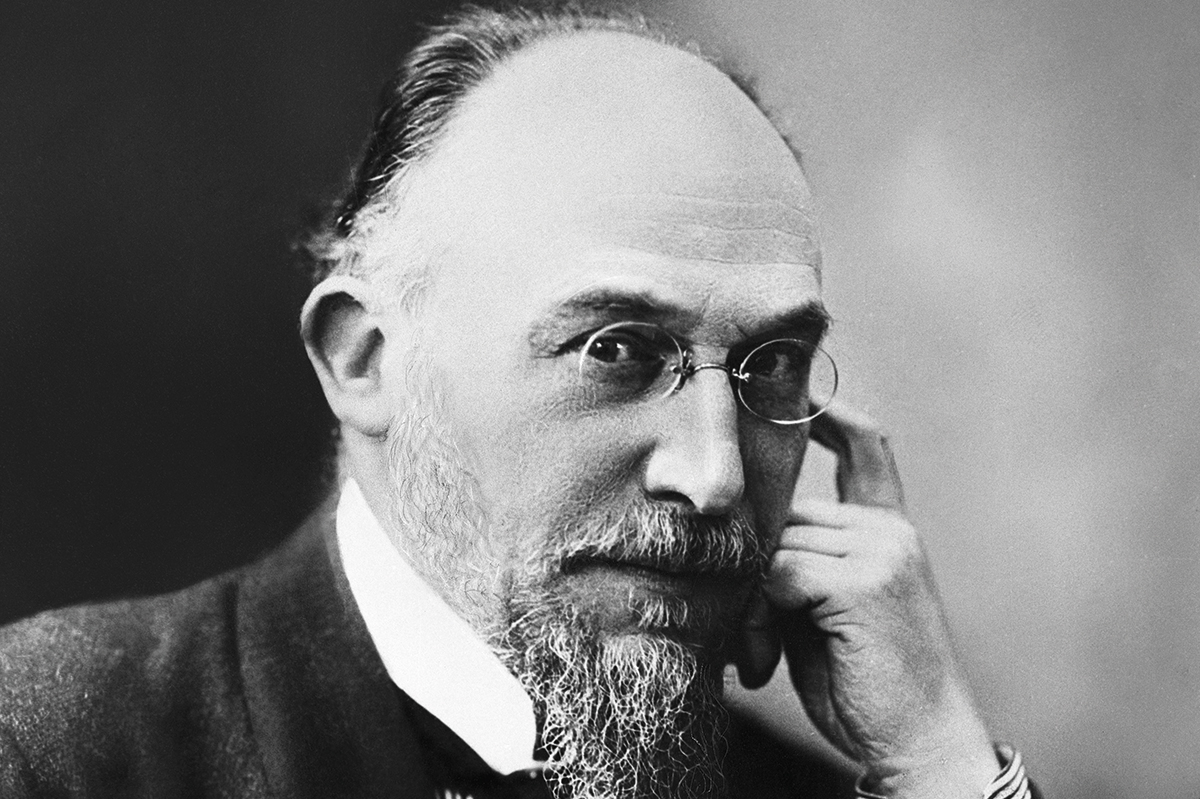

The third and most eccentric project is the brainchild of a pianist from Monaco who describes himself as “a virtuoso transcriber of pop music (video game, japanime, metal).” He is recording all 371 of Bach’s four-part harmonizations of Lutheran chorales on a Steinway piano. I defy anyone to listen to more than a dozen at a stretch without getting bored. But take them one at a time and you’ll be amazed.

The most prominent of these Bach entrepreneurs is Rudolf Lutz, artistic director of the J.S. Bach-Stiftung Choir and Orchestra in St. Gallen, Switzerland. But even he isn’t as famous as he deserves to be. Since 2006 he has led monthly concerts in exquisite Protestant churches at which just one cantata is heard — twice. Between the two performances a secular speaker offers a personal reflection on the libretto, and in a pre-concert workshop Lutz and a pastor delve into the cantata’s theological and musical themes. This is often where he extemporizes and his gift takes one’s breath away. He can turn an advertising jingle into a baroque chorale prelude and vice versa; it will take AI decades to catch up with him.

Lutz has assembled a crack ensemble of young professionals who dance their way through the joyful choruses while also conveying the profound introspection of Lutheran faith. Once the cantatas are completed in 2027 this cycle may eclipse even the celebrated recordings by Masaaki Suzuki and the Bach Collegium Japan. Judge for yourself: the concerts, reflections and workshops are all freely available on YouTube and the foundation’s website.

If Lutz is the world’s most underrated Bach conductor, then Thelma Lovell, who lives quietly in Cambridge, may be the most overlooked Bach scholar. Her 2011 book A Mirror to the Human Condition suggests that the theology of the cantatas can teach us “how to live and how to die” even if we aren’t religious. In her forthcoming magnum opus, J.S. Bach’s Sacred Cantatas: A Cultural Christian’s Companion, she takes us through every cantata in the liturgical year, teaching us painlessly how to understand Bach’s theological and musical language.

Lovell draws on an extraordinary breadth of cultural references: Sophocles, Horace, Keats, Nietzsche, Adam Smith, Terry Eagleton and the Epic of Gilgamesh. She also recommends recordings for each cantata, including interpretations by Harnoncourt, Herreweghe, Marriner and Suzuki. But more often than not she chooses Lutz. Perhaps she feels that he best understands what she calls the question of pulse: “Music, like the heart, has a continuous beat; its pace, whether fast or slow, has a bodily effect. Everywhere in Bach there is a forward impetus that communicates itself as life’s urgency… Bach’s ability to play with danger and then resist it becomes a token of faith’s miraculous power to conquer despair.”

The third project, by Nicolas Horvath, is one that nobody else would attempt. He’s an odd fish. I haven’t heard his video game transcriptions, but I suspect they’re more fun than his six volumes of Philip Glass’s piano music or the painfully amateurish piano sonatas of Anne Louise Brillon de Jouy (1744-1824). On the other hand his Chopin nocturnes, which he performs in multiple revisions by the composer’s pupils, are quite lovely.

Horvath offers us the Bach chorales “for daily calm and inspiration.” Yet he denies us even a glimpse of pianistic color, and surprisingly this rigid simplicity is a virtue, revealing that Bach’s finest hymn settings are among his most perfect creations. If anything, hearing them on the piano highlights their ingenuity — the rhythmic dialogue between alto and tenor, cascading lower voices, pinpricks of dissonance.

A typical chorale lasts for a minute and a half. No wonder the Second Viennese School was fascinated by this music. In the second movement of Alban Berg’s Violin Concerto, the clarinets weave in Bach’s harmonization of the chorale “Es ist genug.” It’s a magical device, but every time I hear it I wonder if Berg has allowed himself to be upstaged. Similarly, Anton Webern’s tiny pieces may reveal the universe in a grain of sand — but Bach got there first.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply