As Van Morrison’s lovely, Oscar-nominated “Down to Joy” plays over the opening credits of Belfast, I immediately accepted that I was being primed for the tears that would surely be flowing in an hour and a half. It’s obvious from the outset that Belfast, Kenneth Branagh’s touching Troubles-set coming-of-age story, is pure Oscar-bait, a film engineered to produce both weepy breakdowns and awards. The ingredients are all there. It documents a historical sectarian conflict, one pitting Protestants against Catholics. A beautiful young family, struggling financially, must navigate the chaos that has descended upon them. Judi Dench, in yet another barnburner of a performance worthy of all the awards, lends the production immediate gravitas, as does the fact that it was shot in “Serious Film” black-and-white.

Branagh takes us back in time to August 1969, where we meet the nine-year-old Buddy (Jude Hill), a lovable lad who makes cheerful banter with everyone he passes. Branagh, who’s on record saying that Belfast is his most personal film — he left Northern Ireland at age nine — paints an immediate picture of the city as a place where children are free to roam and play without a care in the world. The simple pleasures and generational ties that constitute a vibrant community have clearly shaped Buddy’s nascent worldview, as well as the irrepressible joy he radiates as he bounces around the block. His tiny neighborhood is all he’ll need, but as his mother calls him home, the reverie is shattered when Protestant rioters attack the Catholic homes and businesses. Buddy makes it home unscathed to his Ma (Caitríona Balfe), but his world is now complicated, consisting of men, politics and an inevitable separation that will split his life in two.

The success of a historical drama like Belfast hinges on a director’s ability to successfully balance real-life events with the personal stories that drive its emotional core. To Branagh’s credit, it’s always clear that Belfast is less about the struggles of Northern Ireland than it is about the struggling family at its center; the political strife only serves to heighten the familial stakes. Out of these churning frictions emerges the film’s central message that the best of life is found in the relationships we share with those closest to us.

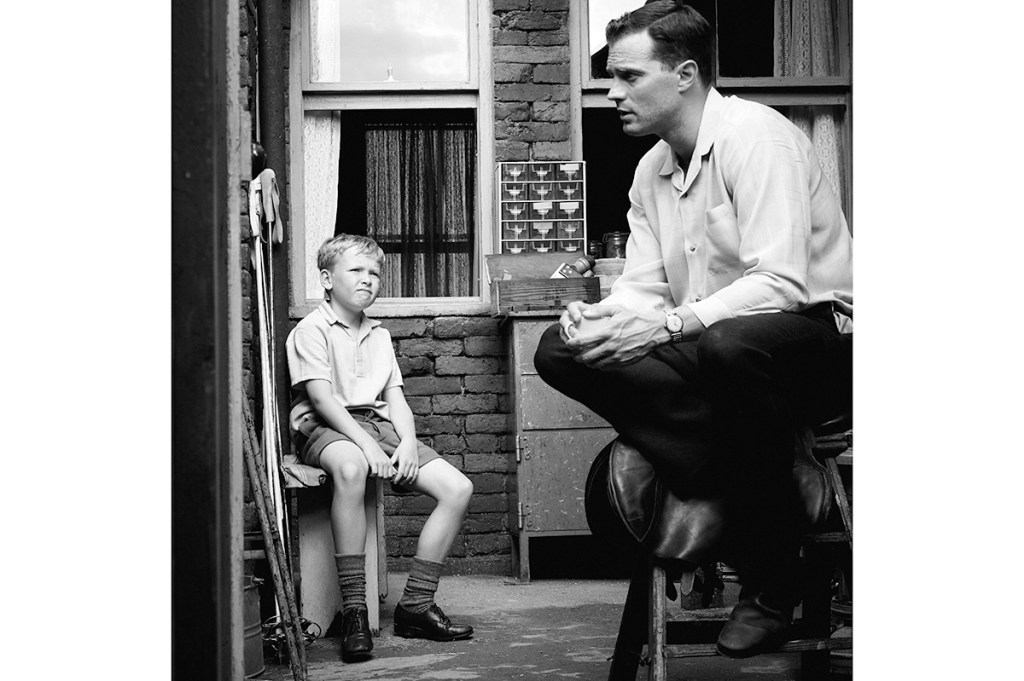

Buddy is the heart of the film, and the family that orbits him makes it easy to understand why he so fears having to leave Belfast. His Ma, a working-class beauty with a ferocious stubbornness to match, has a single goal in life: to give Buddy and his older brother Will (Lewis McAskie) the necessary foundation to make them upstanding men. Pa, played by the terminally stoic Jamie Dornan, spends weeks away from home working in England but remains a hero to his son, who hangs on his every word of advice.

If Buddy is the heart of Belfast, the film’s soul lies with his grandparents, Granny (Judi Dench) and Pop (Ciarán Hinds). The relationship between the crotchety Granny and the pollyannaish Pop epitomizes what Buddy and the family will leave behind if they are forced out of Belfast. The pair’s indestructible bond, built on years of struggle and sacrifice, is grounded in the city. To leave home is to risk destroying the edifice upon which one’s entire life has been built. When Buddy tells his grandfather that all he wants is for his grandparents to join the family in London if it comes to that, the old man can only hug the boy — it’s too late for some to leave. Not that they’d want to, anyway.

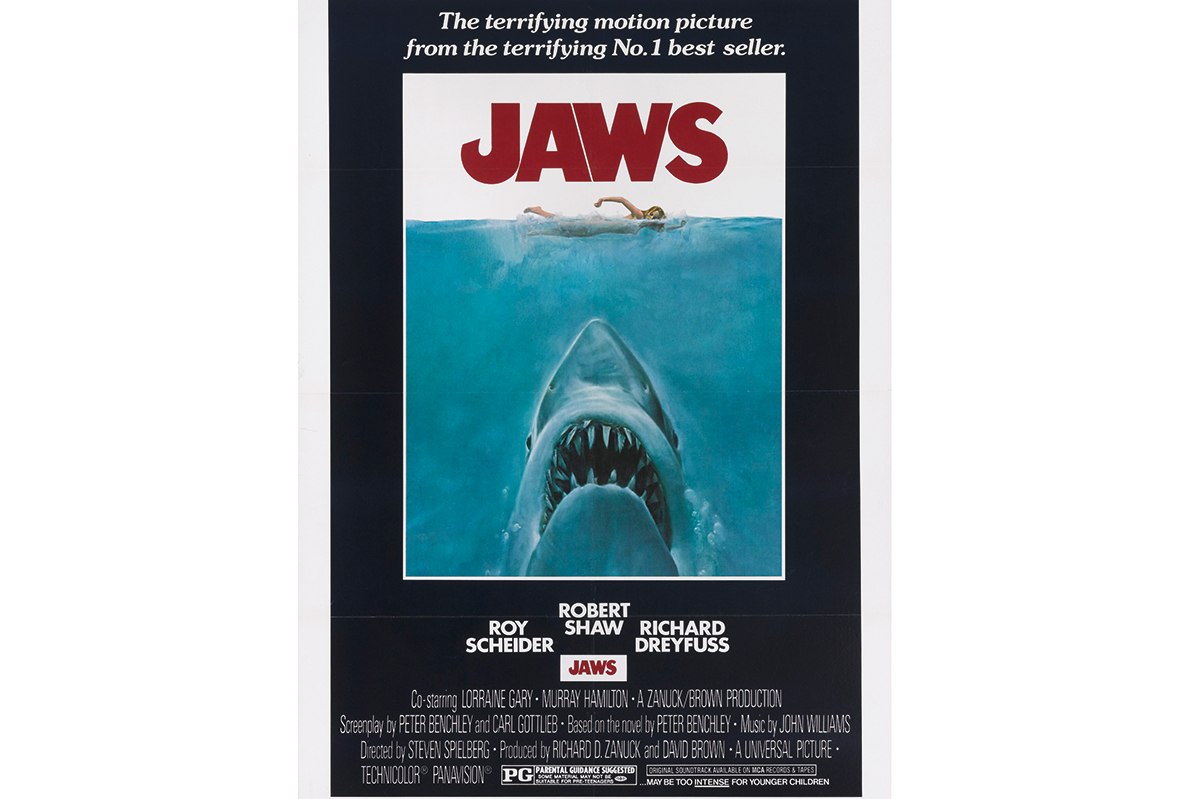

The ensemble cast is brilliant, but the magic in Belfast emanates from the naiveté and enthusiasm communicated by Hill. Framing the film from the boy’s point of view was a masterly touch, as the compact city takes on grandiose proportions when seen through the lens of childish wonderment and bewilderment. Buddy’s first crush reminds us of the purity of youthful infatuation; his rapture when watching American Westerns takes us back to those days when the cinematic experience was truly larger than life. By the time we reach the film’s climax, Buddy’s smallness renders those large historical forces that transform our lives all the more poignant, despite our best efforts to resist them.

The tears, scored to yet another Van Morrison tune, predictably come. Sometimes Oscar-bait is just what one needs to be reminded of the magic of cinema.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2022 World edition.