Ellen Barkin, Al Pacino’s lover-cum-prime-suspect in his comeback movie Sea of Love (1989), once dismissed the artifice of the British acting tradition (by way of an oddly ill-tempered pop at Nigel Havers) by comparing it with the immersive naturalism of the greats of post-war American cinema: Marlon Brando, Meryl Streep, Robert De Niro and Al Pacino. It’s a questionable claim, especially given that in Pacino Barkin had perhaps the least naturalistic co-star imaginable.

He is forever searching for the off-beat, the syncopation that will spring the line open

Pacino is — albeit in his own highly idiosyncratic way — no less theatrical an actor than John Gielgud, more invested in the musicality of his line readings than in fidelity to the real. Think of the terrific scene towards the end of Glengarry Glen Ross( (1992), when his character, the bouncily coiffed real estate salesman Ricky Roma, is tearing a strip off Kevin Spacey’s hapless office manager John Williamson for speaking out of turn and blowing a deal Roma was on the brink of closing. Pacino’s timing is so anti-intuitive as to demand its own notation:

What you’re hired for /is to help us. Does that seem clear to you? To help us. Not to /fuck us up. To help men who are going out there /to try to earn a living-you-fairy. You company man.

Pacino has often taken flak for pushing these freedoms too far. Viewed another way, the shoutiness and eccentric stress patterns of his performance as, for instance, the blind Vietnam War vet Frank Slade in Scent of a Woman (1992) — alongside his Vincent Hanna in Heat (1995) often considered peak shouty-Al — are not meretricious overacting but an attempt to redeem often quite indifferent material. If a line lacks interest, Pacino will supply it himself. He is for ever searching for the off-beat, the syncopation that will spring the line open and introduce a level of intensity not always present on the page.

If only the same could be said of Sonny Boy, Pacino’s eleventh-hour attempt at a memoir. As turkeys go, it is less of a spectacular failure on the level of The Godfather Part III than a literary Righteous Kill: a lumbering, vaguely pointless exercise. Alfredo James Pacino — “Sonny Boy” to his beloved, fragile mother Rose — was born in 1940 and brought up in a tenement in the South Bronx. His father Salvatore left the family home when Pacino was two; with Rose in and out of psychiatric hospital, hooked on barbiturates and subjected to electroconvulsive therapy, little Sonny was largely left to run wild, stealing food and exploring the tenement rooftops with his closest friends Petey, Cliffy and Bruce, all of whom would later succumb to heroin overdoses.

Pacino survived, largely thanks to what guidance the ailing Rose was able to give him. But even as his early successes off-Broadway — notably in Israel Horovitz’s The Indian Wants the Bronx, opposite his friend and frequent co-star John Cazale — led to his first film roles and eventual stardom, he remained (and remains) the feral street kid, instinctual, as financially inept as he is sartorially scarecrowish, scarcely able to feed himself or brush his hair. When, during the filming of the celebrated hospital sequence in the first Godfather movie, he is summoned to lunch with Brando, he finds the older actor — “the greatest of our time” and Pacino’s artistic forefather — sitting on a hospital bed eating chicken cacciatore with his hands. “Is that how movie stars act?” reflects Pacino. “You can do anything.”

It’s an odd lesson to draw from a forty-six-year-old man covering himself in tomato sauce like a toddler in a high chair, but one, nonetheless, that Pacino seems to have taken to heart. Decades later, his sometime dinner companion Elizabeth Taylor hears from a mutual friend that Pacino has taken on a personal assistant. “Good,” says Taylor, “because that boy needs all the help he can get.”

The problem for readers is that, at least in Pacino’s hands, the memoir form is unable to account for his wildness without falsifying it. Sonny Boy is boring. It is bloated with bland observation (“I enjoy hearing [Francis Ford Coppola’s] take on any subject”) and the kind of luvvieism (“So I turned to Jeff [Bridges], who I would come to know in the future as one of the most wonderful human beings and such a great actor”) definitively skewered thirty-six years ago by Nigel Planer in his magisterial spoof memoir I, An Actor.

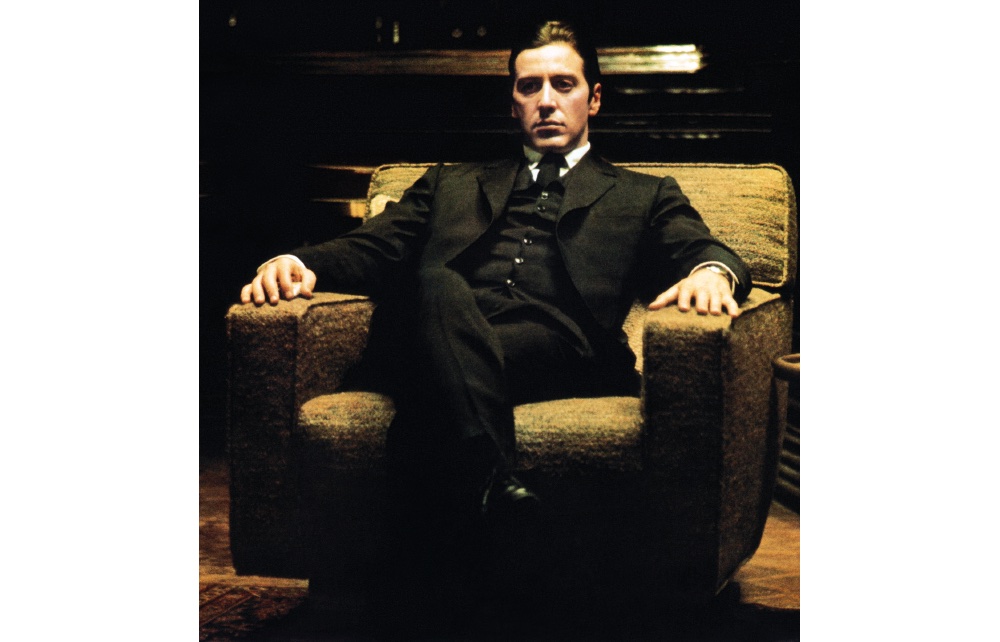

It displays a distinctly wobbly grasp of Greek myth. Pacino compares Tony Montana, his character in Scarface, to Icarus, “flying higher and higher until he exploded.” Worst of all, it is maddeningly short of the kind of behind-the-scenes detail or professional insight that constitute the sole reason fans might be persuaded to buy the book. The filming of the masterpiece The Godfather Part II is dispatched in a few bewilderingly insipid pages. (“Part II does take the character of Michael to a more complex place and has something more insightful to say about his condition.”)

Forget the book. Watch Part II instead, and marvel at Pacino’s control in the breakup scene with Diane Keaton at the Hotel Washington, the identical caesuras he inserts in two consecutive lines: “Do you expect me — to let you go? Do you expect me — to let you take my children from me?” The heavy pauses make the lines a simultaneous plea — that wounded, martyrish, poor-me quality to Michael — and a threat. Pacino is a genius, but of a kind undetectable to the phoned-in celebrity memoir.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.