There’s more than a grain of truth in the popular caricature of a curator as a mother hen clucking frantically if anyone gets too near her nest — not that her eggs are about to hatch, let alone run. The recent threat of the British Council to “deaccession” — to put it more bluntly, sell — its 9,000-piece-strong collection of British art has caused a predictable flurry in the curatorial world. Doesn’t the British Council know that public art collections are sacrosanct and must be preserved for all time?

When I was director of Glasgow’s museums and art galleries, I remember talking to my committee about my long-term plans for the city’s great permanent collection when the leader of the council, Pat Lally, commented drily that there was no such thing as “permanent.” He wasn’t proposing to sell it all. Quite the reverse. He was the most imaginative politician I’ve ever had the pleasure of working with and wanted this massive asset to be used as much as it could. He encouraged and enabled me to create Glasgow’s Gallery of Modern Art, the St. Mungo’s Museum of Religious Art and Life and to convert the beautiful McLellan Galleries into a major international exhibition venue. All he was doing was reminding us of a fact of life.

His comment made me think. Of course everything changes, and our so-called “permanent” collections are in themselves records of such changes. Museums have collected coins to chart the rise and fall of kingdoms, not just to accumulate comprehensive collections of metallic cash. Had Darwin not collected every type of barnacle, he might not have been able to prove his theory of evolution. Without collections, great artists like Vermeer wouldn’t have emerged — as they did much later — from the disregard of their contemporaries. Our perceptions of history, science and art are forever changing, so how can any collection in itself be regarded as “permanent?”

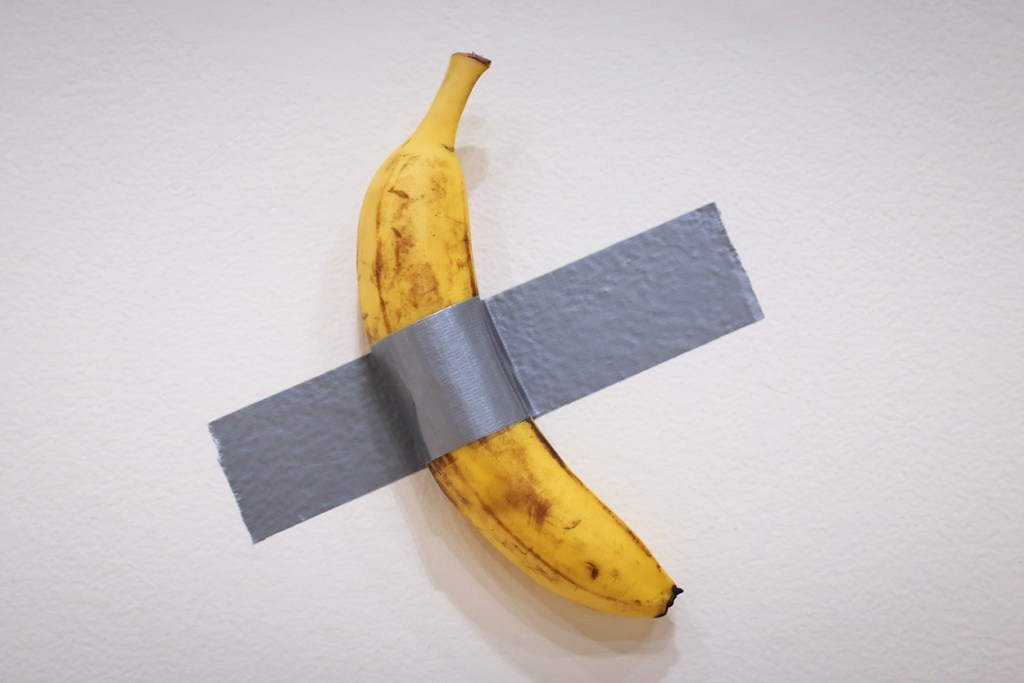

Over the past fifty years, art itself has changed beyond all recognition. How can a banana stuck on a wall with a bit of tape be regarded as a work of art? And yet just such an object sold for $6.2 million in 2024 because enough people thought it was exactly that — unbelievable as it might seem to anyone with eyes in their head and any knowledge of the art of the past. The buyer, the cryptocurrency entrepreneur Justin Sun, emphasized this object’s transience by eating the banana immediately after he’d bought it. So much for permanence!

In 2012, I wrote a pamphlet called Con Art, explaining how all this madness came about, from Duchamp’s theft of the extraordinary Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven’s “Urinal” — which he stripped of its profound meaning — to the nonsense of today. Art can’t just be a found object, still less a mere idea. Conceptual art is a con. Now bitcon art — I wish I’d called my pamphlet that — is one of the most expensive things around. The only “permanent” thing about much contemporary art is its price.

This is something else that’s changed. When people today look at a work of art — however old or recent — they see pound notes or dollar bills, not the art itself. This is a problem peculiar to visual art. Anyone reading a poem or a novel, listening to a piece of music or watching a play or a film, values it for its aesthetic effect, for what it means, not for its price. But money now is all that many see in art, which is one reason why the British Council is tempted to sell off its “permanent” collection to settle a one-off debt.

Why has money become so dominant in art? The reason is simple: all the other art forms are infinitely and affordably reproducible, perfectly suited to their burgeoning audiences. But visual art has remained singular — the unique creation of individuals. This is why many think art is a relic of a past age and has no future at all except to make money.

The marriage of money to art has had a long history. Since the seventeenth century, works of art in the increasingly materialist West began to be regarded as good investments. Art became gilt-edged and gilt-framed. But art was still bought to be looked at, lived with and enjoyed. The absurdity of the current situation is that people now buy works of art not to look at but purely as investments, to be stored in tax-free bonded warehouses around the world, and sold on at a profit, their purpose fulfilled.

The most famous names in contemporary art — I won’t name them and give them even more unmerited publicity — have become in effect brands, their teams of workers churning out supposedly unique objects which are never seen, let alone judged by anyone. People who buy a Rolex watch, a Louis Vuitton bag or a pair of Louboutin shoes, want them to be seen, not hidden away. These possessions might be used just to show off, but at least they still exist in the land of seeing. Now art doesn’t have to be seen at all to exist.

Public collections have played a crucial role in elevating art into the invisible realm of international finance. Absurdly, the taped banana was produced in a limited edition of three, one of which is in the collection of the Guggenheim Museum in New York. The presence of an artist and his or her work in a museum’s permanent collection guarantees the status and therefore the implied quality of their productions for all time.

Museums have, over the past half century, become the banks of the art market. Their permanent collections provide the credit rating for art sales. Ironically, this has given museum collections enhanced protection. The last thing art dealers want is for museums to begin to sell their collections of contemporary art. This would suggest that their curator’s judgment was fallible, or at least changeable. And what if the financial value of these “de-acquisitioned” items wasn’t sustained? Think of the effect on an artist’s prices.

Pat Lally was right. Nothing is permanent. Not even museum collections. That is why I came to prefer the word “lasting.” The job of a curator is to find, promote and collect works of art that are lasting, that excavate and evoke feelings that reach deeply into what it means to be fully human. To identify truly lasting works, curators’ judgments need to stand apart from all transient social, political and financial pressures.

What’s more, adopting a deeper, longer-term ambition for art is vitally necessary for contemporary culture. For the last two decades of his life, Henri Cartier-Bresson, one of the greatest photographers of the last century, gave up using his camera to capture the “decisive moment,” and took up the much slower process of creating images by drawing. As he explained to me, “Our world is spinning out of control. We have to slow things down.”

So, what should curators do with their impermanent collections? They need to select what is still of lasting benefit to their public, and deaccession what isn’t by offering it first to other public collections. If any curator anywhere thinks an object still has a social use, then that public need should take precedence. The British Council could, if it sees no more use for its collections itself, adopt this procedure and offer its works of art to public collections worldwide — since it was founded to promote interest in British culture abroad. Then, if the British Council has anything left, there’s no reason why it shouldn’t sell these items back to the sphere of private ownership whence they all originally sprang.

Then curators, instead of flapping, can concentrate on their main task, which is to enable us to see art not because it happens to be in their collections but because it will endure. This is a priority, for the main task that lies ahead of all of us is to make our world last.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply