India’s fast-growing population now stands at 1.38 billion, just shy of China’s ginormous 1.4 billion. China’s population is rapidly aging, so it’s only a matter of time before a youthful India —average age twenty-nine to China’s thirty-seven — overtakes its communist neighbor and becomes the most populous nation on the planet.

I left India as a child, and just spent two months in Bangalore, selling some ancestral property. Bangalore is India’s booming tech hub and Silicon Valley; most major American tech companies, including Facebook, Google, Amazon and Microsoft have opened large offices there to manage their back-end operations. The city’s population has doubled in the last five years to 12 million, and it’s gone from a sleepy former British army outpost to India’s version of San Francisco.

The ubiquity of two-factor SMS authentication for everything from Uber rides and Amazon deliveries to restaurant reservations was a constant reminder that I was just a number, one in a billion, my identity confirmed by a long string of digits. The experience got me thinking about the psychology of large numbers. How did living among a billion other humans affect a people’s mindset and a society’s architecture?

It’s not all the doom, gloom and disease of Western imagination. Headlines about the deadly surge of the Delta (initially the “Indian”) variant across India, and the sick dying outside overcrowded hospitals, amplified omnipresent fears that a hot, dirty and crowded subcontinent is a hotbed of infection. But when the world’s focus had shifted elsewhere, something remarkable happened.

India’s Covid cases began dropping sharply in the fall, due to an aggressive vaccine drive and surprisingly strong herd immunity. A recent study shows that two-thirds of Indians now have antibodies to the coronavirus, implying that almost a billion have already been infected. With no social distancing possible in the country’s crowded urban centres, it’s possible that the virus, with few vulnerable hosts to infect, just burnt itself out.

It’s fashionable to laud New Zealand or Australia for their zero-Covid strategies, but India’s story of survival without social distancing might offer a better model for the next pandemic. Bangalore, India’s tech hub, was buzzing in the weeks before Halloween, its trademark pubs packed to the gills. My doctor sister marveled that the Covid wards in the city were almost empty despite the frenetic rush back to normal.

Indian consumers are now revenge shopping again after the lockdowns. Impressively, there’s no supply chain or labour shortages. India boasts a vast and hard-working migrant labour force, and once restrictions were eased, they flooded back into the cities for work. Zillions of humans can be a blessing when you need your Amazon package delivered the next day or a waiter to take your order.

Economics aside, India’s massive population sweeps up everyone in its warm embrace, turning loneliness into a Western disease. Most Indians have large families and are blissfully caught up in the cosy web of their extended clan and caste. This sense of community is amplified by numerous religious holidays, when a billion people come together in a burst of color and song and fireworks for a common god. I realized over time, however, that cranking up the volume was part of life in overpopulated nation. With so many people in the cities, you have to shout to be heard. It’s like the logic behind the one-time passwords that are an everyday feature of Indian life. Navigating India feels like trading in cryptocurrencies, with long passwords needed to access various goods and services. I’d understood that I’d need to confirm the transaction with an SMS message when exchanging Ethereum for Bitcoin on a network, but for pizza delivery?

This law of large numbers bleeds into every aspect of life. With so many people competing for the same resources, land prices have skyrocketed in recent years. The 1,500-square-yard plot in Hyderabad that my father bought for a few thousand dollars in 1980 is now worth over a million dollars and climbing. Everywhere in India, I eavesdropped on conversations about land, and the best ways to profit from a spike in prices near a planned airport or business hub. For Indians, land is like crypto, doubling in value every two or three years, and has overtaken gold as the new measure of wealth.

With so many humans spinning the wheel of capitalism, lawyers, accountants, bankers and others in the service sector often just disappear. Not bothering to answer their messages, they behaved like hot girls in the West. I realized after a time there that it wasn’t necessarily an insult. They were overworked and it would be impossible for them to reply to everyone that wanted their attention.

It’s a similar story with friends. The average Westerner might have a few good friends at most, but Indians often have dozens. They prefer to meet in groups, rather than for an intimate chat, and they’re more likely to flake or just disappear without warning. I found this one of the more frustrating aspects of being in India. It’s humbling to realize that you’re disposable, just another personality amongst many. However, this aspect of India also has a silver lining: you too can skip out of engagements without consequence, or fear of creating offense as in the West. Your Indian friends can always rustle up someone else for that lunch or dinner.

I’ve been back in Russia now for almost a month now, adjusting back to life in a low-density population. Russia is the largest country on earth but its population (145 million) is less than a tenth of India’s. Outside Moscow, you can drive for miles without seeing a soul. The Uber driver verifies my identity by cross-checking my name, and there are no codes for anything except cryptocurrency transactions. It feels good to be an individual again with a name —not a number. But it’s winter.

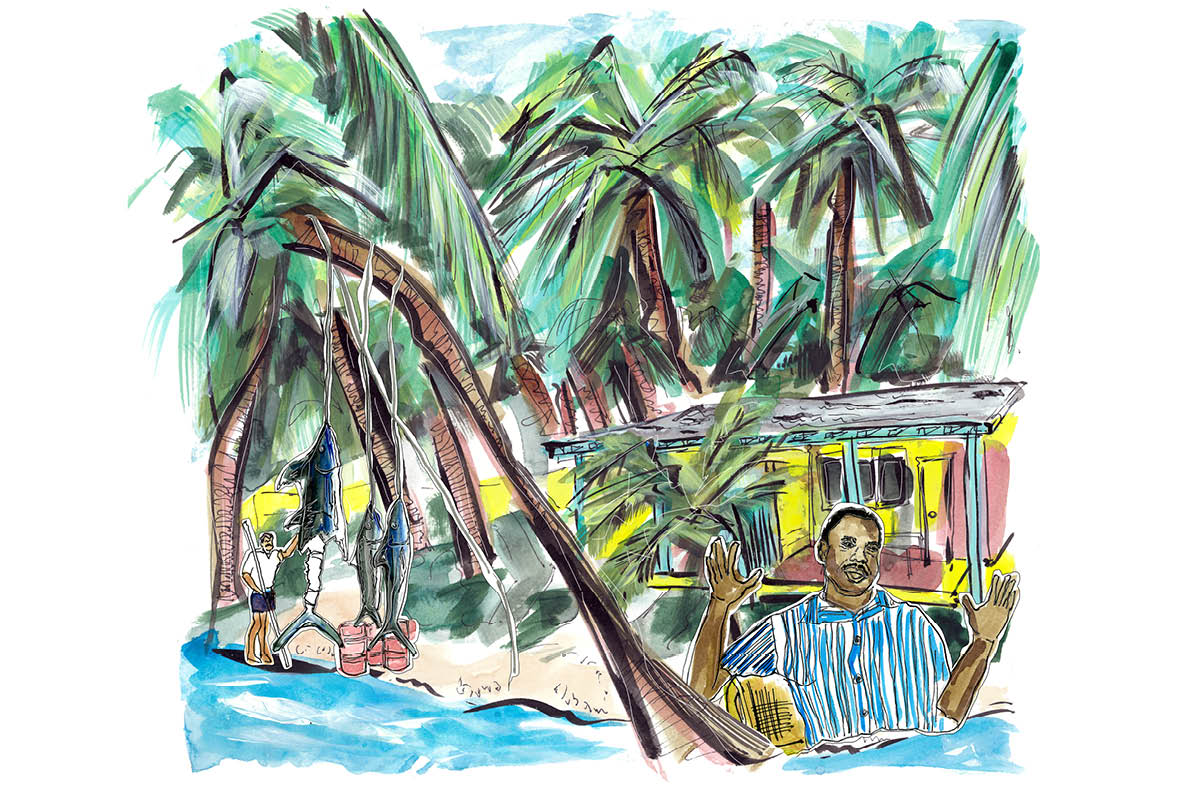

The days are gray, the Russians a prickly and hungover bunch in the mornings. I miss the pleasure the Indians take in their mornings, and the open smiles with which they greet the sunrise. Driving out to a friend’s country house last weekend, past miles of naked birch and chestnut trees, I missed the lush Indian countryside with its undulating palm trees, green rice fields and colorful patches of mahogany and golden shower trees, with their corn-yellow flowers.

A billion people stick together like filings to a magnet. Indians find joy in each other’s company and seek vindication in crowds. It shouldn’t be a surprise, therefore, that India’s beautiful and ancient countryside is mostly deserted and almost as empty as the hinterlands of Russia. Drive just thirty minutes from pullulating Bangalore and you’re among forests and farming villages where the only sounds are the temple bells and the wind as it rushes through the canopies of the forest. It’s magical to switch so easily between the bustling and dirty cities and an unspoiled countryside that seems to exist out of time.

The writer Arundhati Roy famously said that “India lives in many different centuries simultaneously.” The “real” India that’s always been there is biding its time while the modern cities drown in their own poisons. I hope that when India’s population crosses two billion, its countryside will remain as sleepy and magical as it’s always been. I’ll always be happy to return and reconnect with that ancient Indian soul. Om.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2022 World edition.