I don’t know when my father showed André Fleuridas, a friend, the chunk of jade he’d brought back from Burma, where my father was based as a war correspondent during World War Two. Nor do I know how my parents’ friendship with Bonnie and André Fleuridas began. I can only guess. It might have been through art, as both my father and André were artists, and in Weston, Connecticut, where I grew up, artists occasionally gathered in each other’s studios to draw or paint from live models.

Or they might have met at the Weston firehouse where artists, writers, musicians, actors and TV news anchors made up, along with farmers, Weston’s all-volunteer fire brigade. In a small New England town like Weston (the population was about 3,000 when my parents moved there from Westchester County in 1947), the residents who weren’t daily commuters to New York, were on-call to put out fires.

I like to think the jade had been burning a proverbial fire in my father’s pocket until he asked André to reveal a mystery. I rather think, however, that my father and André, a well-known Seventh Avenue jeweler in New York, met through a mutual Weston friend, who had asked my father, who was gifted behind a lens as well as with a stub of charcoal or fine brush, to take some family portraits. The portraits of the Fleuridas family could have been a quid pro quo between friends.

When my father bought the chunk of jade in Rangoon’s gem market, he was told that there was probably a nugget of imperial jade (the most sought after, for its dark green color) inside and that it would take a knowledgeable jeweler to split the chunk without damaging the hidden gem. There was, indeed, an emerald-colored gem inside. André designed a gorgeous ring for my mother that she wore every day until she died. My daughter, Lucy, now has her grandmother’s ring and the vignette that goes with it. André was well known for his stunning creations for Hollywood and New York’s upper crust. Joan Crawford, known for her fabulous jewelry, was one of André’s clients. He’d made a ruby necklace for her that Franchot Tone, her first husband, gave her in the 1930s.

My father’s portrait of the Fleuridas family captured the stylish essence that my family thought was the epitome of understated Gallic taste. In casual, crisp white shirts, Bonnie Fleuridas, with a stunning string of real pearls emphasizing her gracious neck, leans over the rustic post-and-beam fence that surrounded their more-than-charming remodeled barn with their sons Jacques and Penny (André, junior), then in their mid-twenties.

My father also took some shots of the Fleuridas family à table, as Bonnie was a fabulous cook. Her food, served in a collection of French pottery, enhanced the Fleuridas’ savoir faire. I remember learning at perhaps ten that a baguette was not just a diamond but daily bread to the French. It was Bonnie who introduced our family to French cuisine. Everything from an elegant coq au vin to a rustic cassoulet and an assortment of cheeses, served after dessert — not as hors d’oeuvres on crackers. Until my family met the Fleuridas family, sharp Vermont cheddar for my father’s famous omelettes and Swedish bondost (cumin-spiced cheese) were as exotic as my parents got in the cheese department. The desserts? A simple tarte aux poires from the orchard behind the Fleuridas’ barn, or flaming crêpes suzettes.

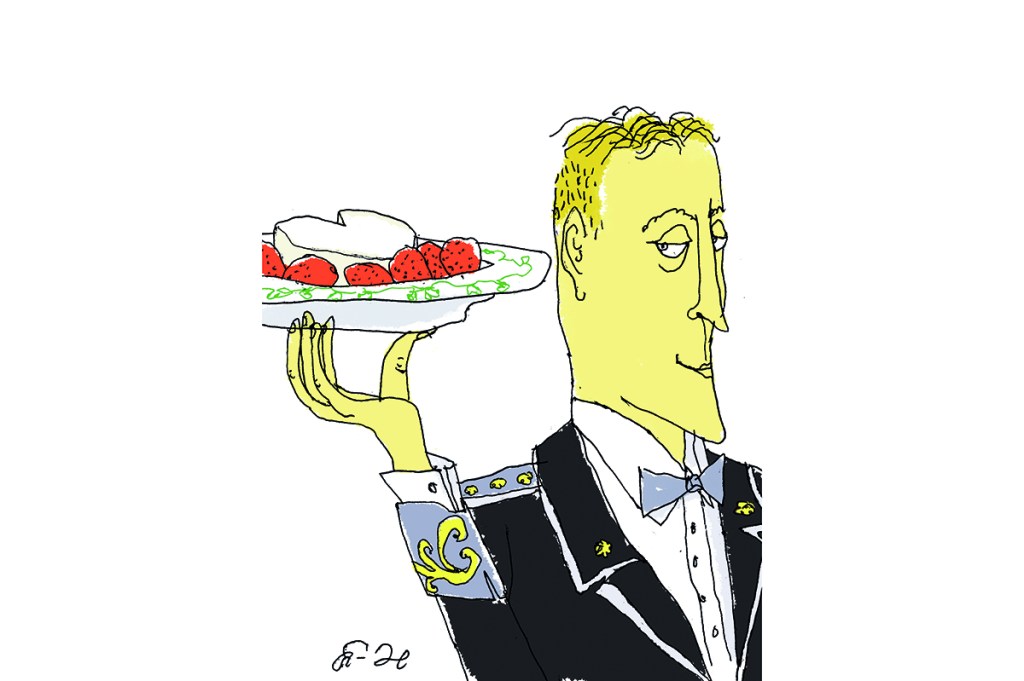

One Valentine’s Day Bonnie made a divine coeur à la crème to celebrate Penny’s engagement to Judy, a lovely strawberry blond. I wondered if the creamy heart surrounded by a necklace of strawberries was to show her love for her future daughter-in-law. Bonnie probably knew that Penny was planning to give Judy a ruby-and-gold necklace that he’d designed.

Penny had followed in his father’s talented footsteps and was working for him. In the 1950s, André opened André Fleuridas Jewelry on Westport’s Main Street. Commuting advertising executives or Wall Street brokers could purchase serious baubles for their wives to assuage their guilt for working such long hours or having lunchtime assignations.

An extramarital affair would never have occurred to my father; my parents’ marriage was as solid as that chunk of Burmese jade. My mother liked to claim that she couldn’t boil an egg when she was married and would tell me, half-jokingly, that I should marry a man who could cook. When my father gave her the jade ring, she added with a smile, “and who likes to shower you with jewelry.”

Valentine’s Day coeur à la creme

Ingredients

A 10 x 10” square of cheesecloth, a large heart mold with perforated bottom, 1 cup crème fraîche or sour cream, 6 tbsp powdered sugar, 8 oz. mascarpone cheese (at room temperature), 1 tsp fresh lemon juice, 1½ tsp vanilla extract, a pinch of salt and 1 lb strawberries, hulled and quartered.

Preparation

1. Rinse the cheesecloth and squeeze until damp. Line the coeur à la crème mold with the square of cheesecloth.

2. Beat the mascarpone, crème fraîche, powdered sugar, lemon juice, vanilla and salt in large bowl with an electric mixer until smooth (about 4 minutes). Press the mixture through a fine strainer.

3. Fill the lined mold with the strained mixture. Place mold in shallow baking dish; cover with plastic wrap. Chill for at least four hours and up to four days.

4. Mix the strawberries with 2 tbsps of powdered sugar and let them stand for thirty minutes. Unwrap the mold and invert it onto a serving plate. Spoon the strawberries around and serve.

Total preparation time: 5 to 25 hrs.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2022 World edition.