In Oklahoma, noodle is both a food and a sport.

For generations, Okies have been jamming their hands in crevices, trying to find the gaping maws of unsuspecting catfish to rip out of their hideaways. And for more than twenty years, they’ve competed at the Okie Noodling tournament held under an hour away from the country bars of Oklahoma City.

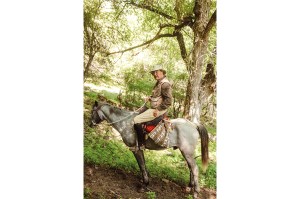

Before covering the tournament, I had to noodle myself, to see what all the fuss is about. In Shawnee, I met up with the award-winning noodler Nate Williams, who runs Adrenaline Rush Noodling. Williams, a former middle-school geography teacher, has the patience you’d expect from someone who spent a decade working with kids, although teaching an eleven-year-old to locate Zimbabwe on a map may be easier than turning me into an even remotely respectable noodler.

We started our day off by meeting at Williams’s home in Shawnee, which has given America cultural icons such as Brad Pitt, sports icons such as Jim Thorpe and Creed Humphrey, and fast-food icons such as Sonic. I came ready with all I needed — swim trunks, sandals, sunscreen and an $18 fishing license in case a game warden stopped us.

And then, we were off! “No Worms. No Wimps. No Worries” is the sport’s unofficial slogan. While the origins of the term “noodling” are unknown, our mission is crystal clear: haul in some catfish using nothing but our bare hands, and maybe a stick or two. Upon arriving at the river, where we will spend the next eight or so hours, we get into roughly knee-deep water. Williams, a self-taught noodler, says that the two options for noodling trips are wading through miles of water or kayaking along; he graciously says that I look fit enough to handle the former.

While the water is not cold, it certainly is murky, rendering the goggles I bought for this excursion completely useless.

At this point, there’s no turning back — not that I would want to; after all, how much can it really hurt to jam your hand into a catfish’s gaping maw?

I found out almost immediately. Williams, through what seem to me to be magical powers, beckoned me over to a literal hole in the wall, where, he said a roughly thirty-five-pound flathead catfish is hanging out. What am I supposed to do? Not catch it with my bare hands?

So, I did as instructed, wondering how I’m even supposed to know what a catfish would feel like. Williams said it would feel like an insanely large bar of wet soap in a shower, and he wasn’t far off. Except I’ve never seen a bar of soap this massive, and soap has never fought me.

Suddenly, BAM, I’ve got her! Or she’s got me. It doesn’t matter. I can’t lose. I won’t lose. I also won’t pretend that it wasn’t a team effort to pry this river monster out from its lair.

Once I had my hand in the fish’s mouth, I tried to grab its lower jaw, “like a suitcase handle,” as I was told. This is much easier said than done, because suitcases only know to run away from Sam Brinton, and not anyone else. After bringing both my hands to bear, though, I landed the catfish.

It was the biggest of the day by far, but it was not the baddest. That honor went to a roughly ten-pound bluecat, the variety known to be more painful to noodle. As I was rooting around in this fish’s hideaway, I suddenly felt like something was trying to pull my thumb out of its socket — because that’s exactly what was going on.

We were the only people we saw for the entire day, allowing us to become one with the river. In one particularly memorable instance, Williams dived headfirst into a catfish home and had me hold onto his leg; I’d pull him out if he jerked his leg three times. As he was buried underwater, I marveled at the level of trust he’d put in me, a total stranger, to be responsible for his life. I was then yanked into reality by him giving me the signal that he needed to come back up for air; no dice on this catfish hole — it must have escaped somewhere else.

By the end of the day, we’d noodled well over 300 pounds of catfish between us, and took five home for the festival’s “touch tank.” I had a simple goal for my first day of noodling: to leave with as many limbs as I started, no fewer. Other than a massive sunburn, and some scars on my thumb that a small catfish left through my glove, I was completely fine. Not everyone is this lucky.

While I knew to look out for snapping turtles and snakes, Williams says that people have actually died while noodling, usually from drowning. His craziest injury came not from a catfish, but from a beaver.

To me, it seems way harder to reel in a catfish by hand than with a rod. Nevertheless, Williams says that in the fishing world, “noodlers are the lowest of the low. They are like the bottom feeders of the fishing world. There just isn’t as much interest, money or attention given to this method of fishing.”

My goal achieved, I could start mentally preparing for the much easier part of the weekend, from my perspective, the twenty-third annual Okie Noodling Festival, located in Pauls Valley, on the other side of Oklahoma City.

The tournament started thanks to a documentary, fittingly called Okie Noodling, that first aired more than twenty years ago. In the film, one noodler laments that bass fishermen have entire festivals, but noodling gets nothing. Well, Bob’s Pig Shop barbecue restaurant took on the challenge and decided to host the tournament, before it grew so big they needed a new venue.

Each June for more than two decades, champion noodlers like Williams have descended on the small town of Pauls Valley, doubling its population from 6,000 to 12,000 for the weekend, local officials tell me. Becky Ledbetter, the town’s tourism director, said that this year people came from as far away as France and Japan.

While Ledbetter emphasized that the festival needs to stay true to its noodling roots, it featured other catfish-free events, like a watermelon crawl and a wet t-shirt contest for men only, along with concerts by big names like the Eli Young Band.

While the festival really is all about the catfish, the organizers needed some ways to keep attendees entertained while the noodlers spent their thirty-six hours all over the state trying to land the biggest (and smallest) catfish they can find.

This is the origin of both the watermelon crawl and the men’s-only wet t-shirt contest. The former “started as a happy accident,” parks and recreation director Jennifer Samford told me. One year, a local supporter donated a ton of watermelons to the festival, and they had to do something with them. That’s now turned into a contest for the kids, who can use only their foreheads to push a whole watermelon over the finish line.

The men’s-only wet t-shirt contest is a little more innovative — and dangerous. Ahead of the contest, organizers “take a double extra-large t-shirt, we wet it, and we wad it up, and we put it in a Ziploc bag and we freeze it,” Samford said. The day of the contest, ten “guys come up on stage, and they are handed a frozen t-shirt, and it’s whoever can get it unfrozen, open and put it on correctly, tag in the back, they’re the winners.” The winner is awarded a WWE-style belt, though all participants get to keep the t-shirts.

The scene is as incredible as you’d imagine. “There are ten adult men, with no shirts on, beating frozen t-shirts on the ground, rubbing them on their chests,” Samford said. “It’s pretty funny. We’re playing silly music in the background. It’s all to have a good time.” The contest, however, is not without its risks. Several years ago, one participant was smashing his frozen t-shirt on the stage when it popped up and clocked him, cutting his head open. “That was a freak accident,” Samford said.

As for the event that everyone has come to see, Williams unsurprisingly was among the top catchers — and one of his children outright won the youth division with a 65.9-pound catfish.

In this year’s competition, Williams was a victim of his own renown; he’s been competing in the tournament for almost two decades, and this year they asked him to help teach festival goers how to noodle.

Still, he came in sixth place in the scuba division with a 51.16 pound fish, but “had to cut our fishing short though because they wanted our family to do noodling demonstrations and teach people to noodle in the big glass tank.” This year’s haul is far from his biggest, which set “a tournament record and the biggest fish ever weighed in at a noodling tournament, eighty-five pounds.”

Wet t-shirts and watermelons aside, the festival is, and always has been, about the catfish and their catchers. Noodling has been going on in Oklahoma for generations, and while the Pauls Valley tournament is relatively new to the sport, its impact in the community, and increasingly, around the world, is something that its vocal fans take immense pride in — and everyone has an incredible time at it, except the tons of catfish that get served up as snacks for the attendees.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2023 World edition.