Colfax Avenue is the longest commercial street in the United States. It’s over fifty-three miles long, from the foothills of the Colorado Rockies all the way through the capital of Denver and out to the Eastern plains. It is littered with single-story, seedy roadside motels, some with working neon signage and some without. Hemp shops and dispensaries have moved in now as well. East of Denver, it has gained a sort of urban-legend reputation for sex work, vagrancy, crime and as of late, migrant gang activity. However, West Colfax is legendary for another reason.

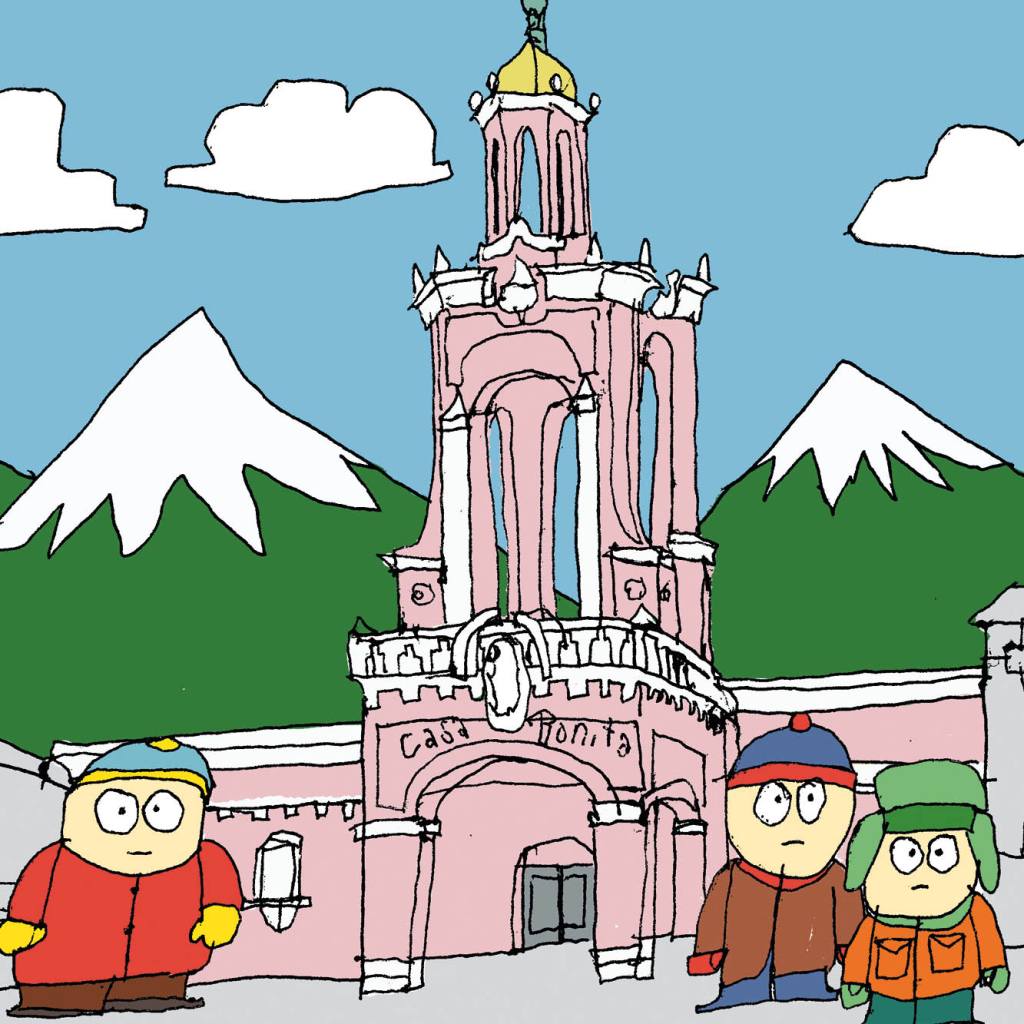

Nestled in the corner of a semi-rundown strip mall in the suburb of Lakewood, next to a coin-op laundromat and a Dollar Store, sits the mythological pastel-pink stucco tower of Casa Bonita. Casa Bonita is not the greatest restaurant in the world — not even a good restaurant — but when I was growing up in Lakewood, it was one of the only real magic getaways we had. Casa Bonita was, in fact, so bad that it was good. The food was notorious for inducing fits of salmonella-laced acid reflux, all for about $4.95 a plate.

Upon entering, your nostrils and eyes were instantly singed by the smell of chlorine and refried beans. It was like wandering into an indoor swimming pool with a Taco Bell. Food was all served lunchroom or prison cafeteria style: grab a lunch tray, a silverware roll in red, green or yellow, and move down a long corridor where the food was dispensed from a small slot opening from the wall. You would then be escorted to one of the hundred or so hidden-away tables in the sprawling 52,000-foot space, past real-life indoor cliff divers, past an arcade, a mariachi band, a puppet show and Black Bart’s Treasure Cave. Where you ended up was anyone’s guess, and that was all part of the dark, musty, magical mystery.

No matter how bad the food was, and it was, the food was never the point of venturing out to Casa Bonita. It was about eating as quickly as possible and then running off to get lost from our parents for the next two hours in caves and arcades, while they sat there and downed watered-down margaritas in much-needed peace.

Casa Bonita was a random wonderland of some of the kitschiest items that could be shoved into one space. It was a suburban white person’s idea of Elvis Presley Mexico, or Fantasy Island. It made no sense. There was the random actor in a gorilla suit just running around. Swashbuckling pirates, a puppet theater, performers dressed up as Black Bart, the dubious “villain” of Casa Bonita. There were mock shootouts on the cliffside where the heroic sheriff knocked Bart into the pool below, to the howls of the crowd. There was a wishing well with a creepy face at the bottom. It was a Spanish colonial, adobe-themed madhouse for kids, our own mini-Mexican Disneyland and asylum.

The last time I visited Casa Bonita was with my group of teenage friends, and it was out of sheer irony. Casa Bonita had become a run-down punchline, even more than it had always been. We were monitored by the staff and security who knew we were there to cause trouble. Then I grew up, moved away and never thought I would see it again.

Casa Bonita became a victim of the pandemic in 2020, when in-person dining was banned statewide. When it tried to reopen, there were payroll problems with long-term employees. Checks bounced. Casa Bonita was the brainchild of Bill Waugh, who built it in 1974, but it has been sold several times over the decades. Eventually a corporate group, Summit Family Restaurants, purchased it, but never did any upkeep of any kind. Summit Family filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2021, and Casa Bonita’s doors closed. Denver — the restaurant was an official city landmark — and investors mulled over what to do with the skeleton of Casa Bonita. Demolition was all but imminent.

Trey Parker and Matt Stone met while attending the University of Colorado in the early 1990s. Parker grew up in Morrison, Colorado, and Matt Stone grew up in the southwest suburb of Littleton. They were two sons of the Eighties who both visited Casa Bonita multiple times, just like me and thousands of other local kids. Parker and Stone would go on to create the Comedy Central animated series South Park. What started out as a crude show of in-jokes and elementary school crassness blew up into a cultural phenomenon.

Parker and Stone left Colorado for Los Angeles years ago but remained locally grounded; this routinely came out in their work, both with South Park and their other productions such as the hit Broadway play The Book of Mormon. Their ability to act like Hollywood outsiders looking in has made them both counterculture icons.

In 2003, at the height of its popularity, South Park aired an episode titled “Casa Bonita.” Eric Cartman, the overweight main antagonist of the show, is left out of a group invitation to Casa Bonita; jealous of his enemy Butters’s invitation, Cartman devises an elaborate plan to replace him. When the plan goes wrong and the police get involved, Cartman retreats into Casa Bonita for a final speed run. He yells obscenities at the Cliff Divers, dresses up in a cowboy outfit for an old-timey Wanted poster photo (yes, you could actually do that) and demands that the restaurant’s world-famous sopaipillas are brought to his table as he raises a mini-Mexican flag for service. (The sopaipillas were always the only good dish at Casa Bonita.)

When the police finally catch him, they say, “Well, kid you made an entire town panic. You lost all your friends and now you’re going to juvenile hall for a week. Was it worth it?” Cartman, floating in the cliff-diving pool exhausted, replies “totally.” South Park put Casa Bonita on the national map and gave it an entirely new level of cult fandom. Parker and Stone named South Park’s production offices in Los Angeles “Casa Bonita.”

When Casa Bonita closed its doors in spring 2021, some of those local cult fans organized rallies outside on the curb. They held signs saying “Save Casa Bonita” as cars rushed by honking in support. Local news aired segments interviewing the hipsters gathered at the now-defunct fountain. Stone and Parker heard them.

In September 2021, while appearing with Colorado governor Jared Polis in a video Q&A, Parker and Stone announced they had purchased Casa Bonita out of bankruptcy litigation. They vowed to keep it the same as it had always been: the Cliff Divers, the gorilla. Everything.

There were problems right from the start. Stone and Parker purchased the space for $3.1 million and without an inspection. What they didn’t realize is that the entire indoor and outdoor space had to be completely gutted. Casa Bonita had been neglected for decades; even Employees of the Month wanted their names removed from the placard on the wall.

This was not going to be the patch-up project they had planned on. There were actual death traps everywhere. In the indoor lagoon pool, cliff divers had been swimming under exposed electrical wiring. Dead pigeons had fallen into the kitchen ventilation shafts, dropped there by a hawk residing in the tower belfry. The famous fountain outside had to be completely ripped out and rebuilt. The entire electrical system and HVAC, which also included the indoor pool and entertainment operations, was faulty. Mold had permeated almost every sculpted crevasse.

The original renovation budget was $6 million. In the recently released documentary Casa Bonita Mi Amor!, Trey Parker, inspecting the renovations, seriously considers backing out of the project, which had ballooned to a whopping $32 million, due to safety code updates, kitchen remodeling and basic repairs. The South Park-inspired cosmetic touches Parker wanted to add weren’t even in the budget anymore. They were bleeding money just to get the property back up to code and said that it may never open.

As Parker and Stone debated their options, of closing it down or plowing forward, Parker, who was particularly attached to Casa Bonita — he hoped his daughter might experience it — said, “If we can’t do this, I honestly don’t know who can.” There were several months of delays for soft openings and missed deadlines. The locals became restless.

But on May 26, 2023, almost two full years after they’d bought it, and a final repair budget of $40 million, Casa Bonita had its soft opening, and then several months with limited clientele as the owners tweaked the new experience. While Casa Bonita appears to be the old Casa Bonita, Parker and Stone’s fingerprints are all over it. There is the voiceover that comes over the speaker system — “Have you made your way to the puppet show yet?” in Parker’s classic Mr. Garrison-style theater voice. There are the skeletons with South Park voices warning of the dangers of Black Bart’s cave.

The puppet show’s script is a bit more adult and darker. The performers who wander around have a bit more of South Park’s wry sense of humor. The Sorcero Magic show remains ironically bad on purpose, like a discarded Book of Mormon skit. Some of the old games don’t work and I have to wonder if they did that on purpose.

Then there is the Cartman table. Seated at the same table where he downs his sopaipillas in the episode is a life-sized Eric Cartman.

The food is different, too. It’s been updated by a local chef poached from a Denver cantina. The days of $4.95 combo plates are gone.

And it’s still not really Casa Bonita. The crowds are a mixture of old Gen X tatted hipsters there to enjoy the ironic nostalgia, mixed in with parents and families bringing their own kids for the first time. The smell of chlorine mixed with musty, alcohol- imbued carpet is gone. Gone is the cafeteria lunch line; in its place are $17 margaritas. It feels as though is the best fan film version of Casa Bonita that could have been made. The love is there, but the authenticity feels hollowed out a bit. But I still walked away feeling like my tab was going to a good cause in helping Parker and Stone make up for the expenditures they hadn’t planned for. As my waiter told me, “Trey and Matt were literally the last thing standing between this place and the bulldozers.” In the end that’s all that matters — Casa Bonita has indeed been saved, by the only two guys who could possibly have saved it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply