“You have a big mountain to climb!” is not the sort of text you eagerly await from your girlfriend’s father. But Billy, a true Southern gent, meant no ambiguity. As dawn cracked the alarms sounded in our Airbnb and six of us bundled into the back of the Dodge. A cool mist hung in the valley as “Baba O’Riley (Teenage Wasteland)” started up on the radio and got the blood running. At 6:15 a.m. we entered the shadow of Emigrant Peak, which at 10,921 feet, commands Montana’s Paradise Valley.

Emigrant owes its name to Thomas Curry, a pioneer who struck gold in a creek on the east side of the mountain in 1863. Within two years, forty cabins had sprung up and Curry’s Gulch became Emigrant Gulch for its steady influx of migrant gold diggers, including legendary trappers and frontiersman Jim Bridger and John Bozeman. By 1866, Indian attacks and harsh winters had left the settlement, by then called Yellowstone City, abandoned, but not before it had dispatched wagonloads of plucky prospectors throughout the North Absaroka and Beartooth ranges.

Emigrant rises 6000 feet above the Yellowstone River and owes its bulk to volcanic movements in the Eocene period, when Brontotheres, or ‘thunder beasts’ (early ancestors of the rhino) still roamed the North American landmass. At a push, it can be hiked in four hours, with an elevation gain of 4,687 feet. The hike is beautiful — taking you alongside a burbling creek and through tall grasses and wildflower meadows — but it is not for the faint-hearted. The last half mile or so involves navigating a sheer ridge and scrambling over rocks and scree past several false peaks and ice pockets, before you finally reach the steep-sided summit knob. Despite having sprained my ankle the previous weekend at Royal Ascot — where free booze and an overenthusiastic Argentine friend compelled me to hurl myself onto the track — I summited without a problem, albeit loaded up on Advil.

At the top we toasted with local Cold Smoke beer, braced the sharp winds and took cheesy pictures. The day was a clear one and we could make out twelve mountain ranges, stretching into Idaho and Wyoming. To the north we had a good view of the Crazies, an abrupt shoulder of mountains the Crow considered sacred (I’m told this is something to do with the peyote thought to grow on its slopes). In 1847, the last great Crow leader Chief Plenty Coups went on a four-day vision quest up Crazy Peak, fasting and slicing off the tip of his index finger. At the summit he experienced a deadly accurate series of visions: the coming of the white man; cattle replacing bison on the plains; he even saw himself childless and dying in a log cabin. He didn’t see Hokas and ski poles but you get the idea. Today these mountains are a mecca for summer hikers and winter skiers. To their west runs the Yellowstone in all its shimmering glory, winding its way through Paradise Valley and eventually spilling into the Atlantic via the Gulf of Mexico. Beyond the river lies the Canadian ranges. “Big Sky Country” says it all.

We spent the rest of the week at a dude ranch nestled in the foothills of the Gallatin Range.

On Day One, each guest was assigned a horse. Mine, Cornelius, was as strong and unrelenting as his biblical namesake and had an insatiable appetite for grass. Since I’m a novice rider, this meant that we were engaged in a constant tug of war. I can still hear the wranglers, straight out of Montana State’s Equine Science Program (who all somehow looked like young Jessica Simpsons) crying out, “Don’t let Corn eat!”

The riding was magical and the views breathtaking. Apart from other ranch guests we didn’t see a single soul for a week. Bald and golden eagles soared over the pines; pronghorn antelope, North America’s fastest land animal, gamboled over the grasslands. One afternoon we drove through Yellowstone National Park and spotted five bears (grizzly, brown, cinnamon), herds of bison as far as the eye could see and a lone coyote howling on the roadside.

With all sorts of grouse and other game birds, Montana is a paradise for bird hunters. But it’s also at the center of a heated national debate over the use of lead ammunition. When a lead bullet strikes a big game animal it expands and scatters toxic fragments throughout the meat, which often proves fatal to the eagles and other scavenger birds which swoop down on hunters’ leftover gut piles. Non-lead alternatives like copper don’t fragment and are much less toxic. In 2019, California enacted a lead-ammo ban which has significantly reduced blood-lead concentrations in golden eagles, turkey vultures, and endangered Californian condors. The Democrats have been trying to roll out this band nationwide but it keeps getting shot down by Republicans; non-lead alternatives are more expensive and the move is seen as a classic case of federal overreach. But as unleaded ammunition prices become more competitive, the movement is gaining ground and conservation NGO’s have even started subsidizing hunters who make the switch. In certain gun shops in Montana, in a program backed by Home Depot co-founder Arthur M. Blank, hunters can now get $20 off the cost of a box of nonlead ammo. Some have made the switch voluntarily, preferring, say, the standard 5.56mm copper bullet which, though lighter, has been shown to perform better at higher velocities and to be more effective for hunting big and dangerous game, like elk and buffalo.

One morning we went fly-fishing with a ranch hand from Lynchburg, Virginia. Wild blue eyes, camo cap, Sam was a real rebel type. “Bam-bam!” he hollered, shooting an invisible rifle as two geese flapped by over the water. We cracked a beer. He helped guide my line into the current. After fifteen minutes, I snagged my first catch, a sixteen-inch cutthroat, one of three sport fish native to the Yellowstone, named for the red slash along its jawline. State regulations forbid you from pocketing more than two fish per day on the Yellowstone but I was happy with my one and even happier to release it. Sam taught me how to fly-fish — he also taught me that on eBay you can now buy “pre-gay Bud Lights” for a hefty premium.

Dinner that night was elk, washed down with a Californian cab. Afterward, I tried to teach half-a-dozen people how to play Perudo, a version of the ancient South American game of liars’ dice. It proved too complicated — I was accused of inventing the rules — and when someone suggested we instead play sloppy dice this was met with hoots of agreement and another round of drinks. In “sloppy” you have six dice and six rolls to throw the highest score possible, but you must roll a one and a four to qualify. Buy-in is twenty bucks; if you don’t qualify, you add another twenty to the pile. If you’re “sloppy” and lose a die on your throw, another twenty. If two people tie for high the turn circles back and so does the betting. It is completely luck-based, devoid of any real skill, and devilish good fun. One guy walked off with $750 after twenty minutes.

Fourth of July, 2024. The hundredth anniversary of Montana’s oldest rodeo, the Livingston Roundup. Families piled high in the stands on a warm summer’s evening eating glizzies (hot dogs) washed down with cans of Busch and Happy Dad. Stetsons and plaid shirts galore. A chopper flies by trailing a huge American flag. A clown grimaces from a massive Coors Banquet barrel placed precariously in the middle of the arena. Two announcers kick off the evening’s entertainment: “And now, please give it up for Hawk Whitt from Thermopolis Wyoming!” Team Roping, Tie Down Roping, Barrel Racing, Bull Riding. This was cowboy channel in real time. Kids, clasping elephant-ear pastries, watched with mouths agape. How could you grow up seeing that and not want to be that? Rodeo cowboys have short careers; they’re often crippled after five or ten years in the sport, with serious head injuries occurring at a rate of up to 15 per 1,000 rides (for NFL players it is 5.8 per 100,000 players). “And now, Tuf Case Cooper from Decatur, Texas!” Imagine having a hometown like Tomahawk, Alberta? I was a long way from Royal Ascot.

The undisputed star of the show was the “one-armed bandit John Payne” who entered the arena on a calico horse, trailed by a red, white and blue and painted zebra, “a ten-year-old performing stallion trained to do whatever Payne wants him to.” My animal rights conscience was at snapping point and I was relieved that all Payne’s act amounted to was him riding atop a moving trailer, zebra in tow, lunging his horse furiously and using his one arm (electrocution incident, we’re told) to fire off a round off into the sky.

As “Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue” blared through the speaker, news pinged through on my phone that Rishi Sunak had just held onto his seat in an electoral wipe-out for the Tories. Fireworks erupted over the stands as Toby Keith crooned, “Cause I’m proud to be an American.” I was about ready to pledge my allegiance.

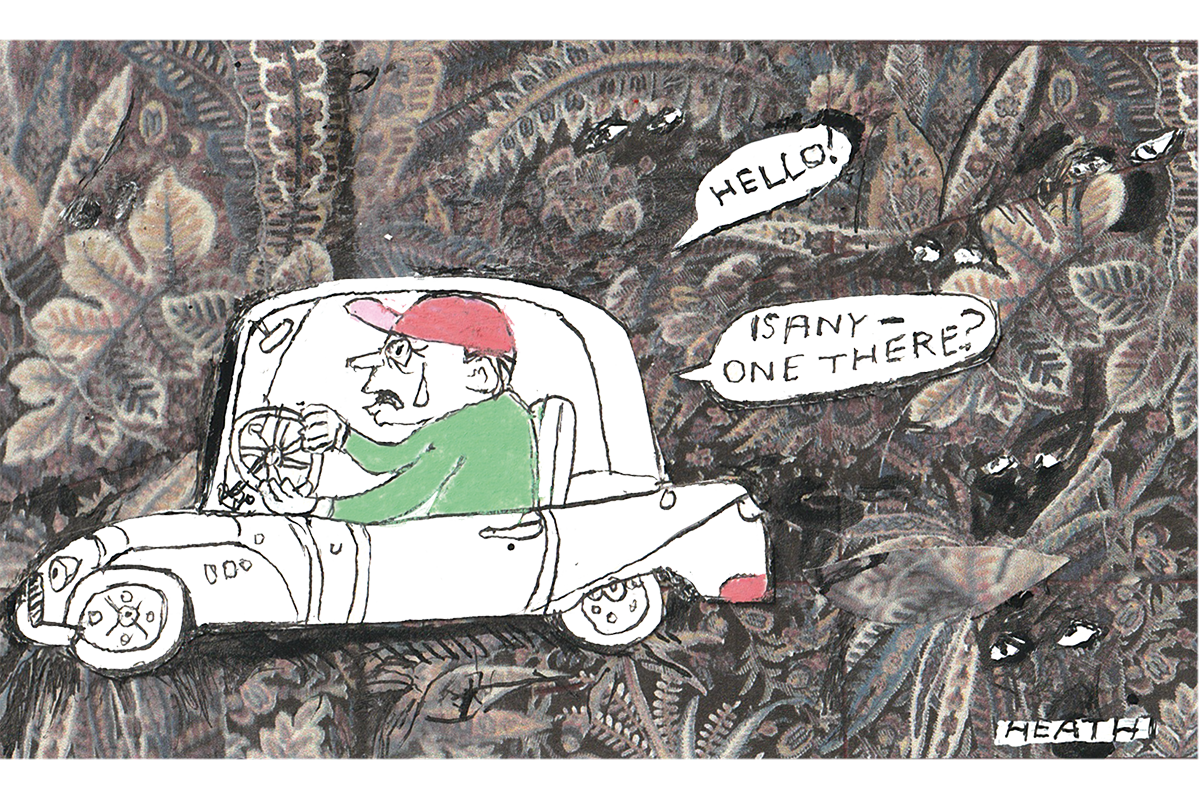

Walking back to the car we passed a blacked-out pickup truck. I turned my head as the window rolled down. “How y’all doing,” I ventured, in my best Western drawl. “Wassup cowboy” came the response. I had passed. “See, I’m a cowboy,” I told my girlfriend. She broke my heart. “Orson, they were being mean. They were mocking you.”

After ten days in Montana, New York City’s Dimes Square was an assault on the senses. The heat was pushing 90 degrees. People ogled each other helplessly. At night, a mouse scuttled across our bedroom, performing its own little rodeo on the lino floor. You couldn’t sleep for the deafening but totally necessary air-conditioning. Every meal cost twice as much as it should have, and we questioned why anybody would want to live here. We thought back to Montana, to what John Steinbeck said about it in 1947:

“I’m in love with Montana. For other states I have admiration, respect, recognition, even some affection. But with Montana it is love.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply